Theh Polar (Kaithal): Eviction notices from the Archaeological Survey of India have landed in this small Haryana village. Again. It jolted residents of Haryana’s Theh Polar village into action. In the last two weeks, they’ve launched a frenetic round of strategy planning meetings, appeals to local politicians, and a crowdfunding drive to fight the eviction in court.

At stake is a Mahabharata-era excavation to find evidence of India’s ancient history, dating back to 1500-900 BCE. The last time archaeological excavation here took place was in 2013, with earlier digs in the 1930s and then 1960.

Pre-Independence archaeologists found earthen pots, coins, and copper seals, but the artefacts were sent to Lahore. The annual ASI report from 1934-35 is the only pre-independence record of Theh Polar’s archaeological significance.

“We have no idea about the antiquities and the excavation of that time but this site has huge potential and needs more excavations,” said an ASI official.

Most of the 5,000 villagers are children and grandchildren of farmers who left their homeland in Pakistan and fled to India during Partition. Displacement shaped their past. Now, they’re determined it won’t define their future. This time, they say, they won’t move.

“We ran away from Pakistan. We don’t want to be homeless again,” said 75-year-old Moti Ram, who, along with other refugee families, built his life on the ancient ruins and mounds that dot the 48.31-acre site in Kaithal district. The catch is that the ASI had bought this land for 56 rupees 6 paisa and 3 annas back in 1926.

With this standoff, a long-forgotten land dispute has become a flashpoint where questions of history and homestead collide. The ASI is barrelling forward to reclaim this land in its largest, most complicated eviction drive yet. It will set the template to clear other key sites in Haryana where the ASI is struggling to remove cattle and settlements. These include Rakhigarhi, Asigarh Fort in Hansi, Ther mound in Sirsa, Naurangabad mound in Bhiwani, and Khokrakot mound in Rohtak, to name a few.

This place used to be an ancient city, which was destroyed in a natural disaster. Later it was resettled. Then it was named ‘Theh Polar’. Theh means the place where there was once a settlement

-BB Bhardwaj, historian

At Theh Polar, the conflict is based on what some archaeologists have conjectured could lie beneath. They argue that because of its proximity to Kurukshetra, the village could well be the site of a settlement destroyed in the battle between the Pandavas and Kauravas. And like the excavations at Deeg in Rajasthan, it’s part of the Narendra Modi government’s drive to dig deeper into India’s ancient roots and unearth compelling evidence of the Mahabharata period. If all goes as planned, it could be part of an archaeological tourism trail linking Kaithal, Kurukshetra, and Hissar.

“Theh Polar is one of the important and notified protected sites. To know the exact chronology of this site, detailed excavation is needed and for that removing encroachment is must. Theh Polar village history goes back to the Mahabharata period but for many decades it has been in illegal occupation,” said KA Kabui, superintending archaeologist at ASI’s Chandigarh circle.

The villagers are having none of it. Moti Ram’s nephew, former sarpanch Shravan Kumar, is leading the charge to save his village. He’s collected more than Rs 2 lakh so far and is preparing for a long legal battle.

“The future of all of us is at stake,” said 55-year-old Kumar, puffing on a hookah. “We have decided to fight together for our survival.”

Since 15 May, villagers have received a flurry of notices to vacate their homes. In response, they have revived the ‘Polar Bachao Samiti’ that they’d first formed two decades ago.

Also Read: Haryana’s Agroha has caught ASI interest after 44 yrs—as part of a new heritage tourism circuit

Mahabharata dreams, modest finds

The stakes are high for the Archaeological Survey of India, intent on finding missing links to the Mahabharata period. Theh Polar has been excavated three times in the last century.

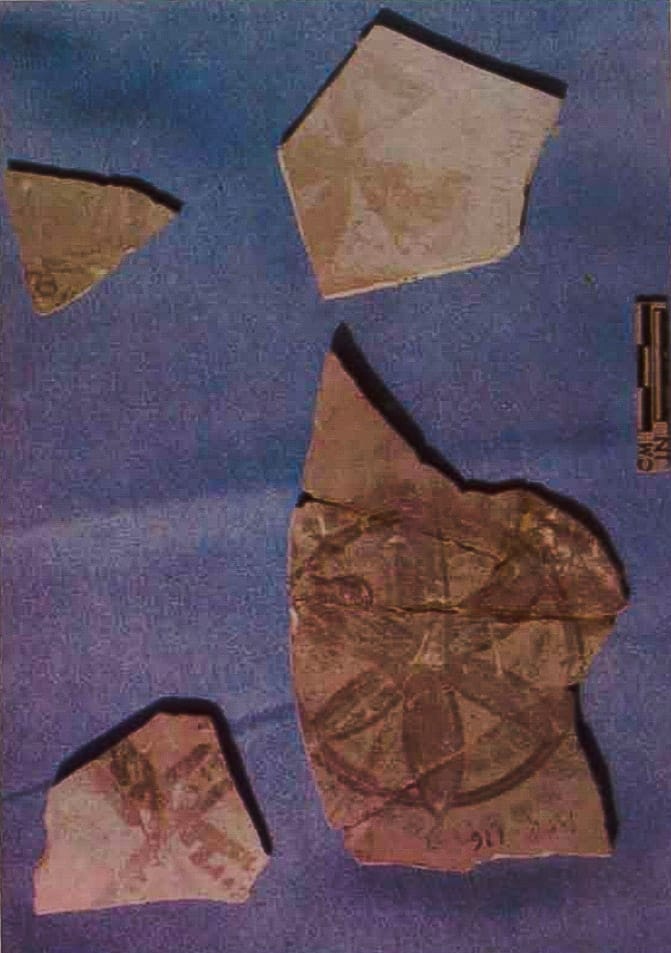

The first dig was in 1933-34, but the findings were mentioned only in passing in the ASI annual report. Some three decades later, archaeologist Shankar Nath did a small-scale excavation of the site and reported finding Painted Grey Ware (PGW), a type of pottery associated with the Iron Age in the Indian subcontinent, according to the Haryana Tourism department website. This created quite a stir, especially because veteran archaeologist BB Lal had linked PGW to the Mahabharata era.

“This place used to be an ancient city, which was destroyed in a natural disaster. Later, it was resettled. Then it was named ‘Theh Polar’. Theh means the place where there was once a settlement,” said BB Bhardwaj, professor, historian, and former president of the Indian History Compilation Committee, Haryana.

The third excavation came in 2013. It was limited to one week and to just a small plot of land because by then Theh Polar had grown into a full-fledged village. It was carried out under the direction of the Punjab and Haryana High Court, with ASI’s Chandigarh Circle Superintending Archaeologist VC Sharma overseeing the dig.

The team unearthed pottery from the Kushan period, estimated to be about 2,000 years old, along with vases, earthen toys, and bricks. The finds are now housed in the ASI’s Chandigarh Circle collection.

There used to be big pits in many parts of the village when I was a child. Often children and even adults would fall into them. These were the remnants of past excavations. But we filled it with soil and built houses

-Raj Rani, Theh Polar resident

Today, the patch of land that was excavated in 2013 is a flat, open plot. There is no ASI fencing. Villagers say the dig turned up nothing of value. “They just wanted the land, so they created the hype,” said one.

The site’s fame has certainly grown in Haryana. In 2021, it even featured in a Haryana Staff Selection Commission recruitment exam. One of the questions was: “Where is the ancient site of Theh Polar located in Haryana?”

Now, the ASI is preparing to restart excavation, and is banking on past precedent. In 2008, the Punjab and Haryana High Court directed that encroachments on protected monuments and sites should be removed with the help of local administration. Since then, the ASI has conducted eviction drives across India, from Delhi to Sambhal in Uttar Pradesh to Nalanda in Bihar.

But by its own admission, progress has been sluggish. In the last 20 years, it’s succeeded in reclaiming only two sites, both in Delhi—Barapullah bridge in 2024 and Tughlaqabad Fort in 2023. The scale of eviction at Theh Polar would be unlike anything attempted before.

Back in Chandigarh, lawyer SS Momi is busy preparing to challenge the notices in the Punjab and Haryana High Court. He is confident that the villagers have a stronger case this time.

Gearing up for a fight

Shravan Kumar surveys the village with its pucca brick and cement houses. There’s a school painted in bright blue with a pathway made of paverblocks. The local stores do brisk business, as does the marketplace. Many villagers own cattle. The snag is they don’t own the land.

Theh Polar is one of 3,695 centrally protected monuments and sites under ASI. Haryana alone has 90 such sites of national importance. While the first ASI eviction notice came in 2005-2006, followed by another round a decade later, nothing changed on the ground. But now things are heating up. Since 15 May, villagers have received a flurry of notices to vacate their homes. In response, they have revived the ‘Polar Bachao Samiti’ that they’d first formed two decades ago. The members have increased from 21 to over 50.

Back in Chandigarh, lawyer SS Momi is busy preparing to challenge the notices in the Punjab and Haryana High Court. He is confident that the villagers have a stronger case this time. In 2007, they had appealed an earlier eviction notice, but the HC dismissed it after the ASI produced land documents.

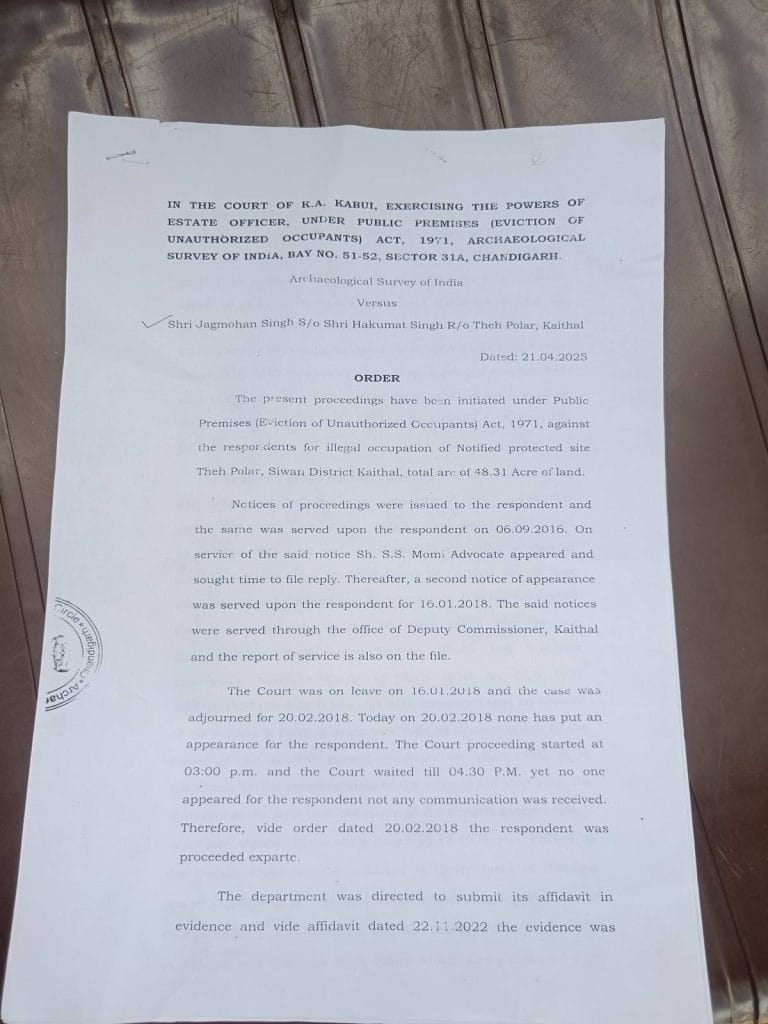

“The current notice served to the villagers is based on an ex-parte order [by the ASI] in which the villagers were not given a chance to argue their case,” said Momi who plans to file his papers in court next week. Kumar engaged him to represent Theh Polar village almost a decade ago when the ASI served them eviction notices in 2017 and then again in 2018. The notice that was sent to them individually last month is the fourth and latest warning.

Nothing concrete was found here even in the excavation of 2013. On the other hand, the government has been providing all the facilities to the people since Independence

-SS Momi, lawyer

It cites an ASI order dated 21 April, stating that proceedings have been initiated under the Public Premises (Eviction of Unauthorised Occupants) Act 1971 for illegal occupation of a “notified protected site”. Momi shrugged it off with an insouciance that has injected confidence among the villagers. He explained that the ASI itself issued this decision under Section 4 of the Act—which allows estate officers to issue a written notice if they believe someone is occupying public land without authorisation.

“Nothing concrete was found here even in the excavation of 2013. On the other hand, the government has been providing all the facilities to the people since Independence,” he said, referring to roads, electricity, water supply, and inclusion in government schemes. Residents also have voter ID cards, ration cards, and Aadhaar.

The irony is that the Kaithal district administration knows nothing about this ongoing tussle. According to the public relations officer, the state archaeology department has not informed them of the eviction notice.

When the notices started arriving at the houses of all 206 families in May, villagers turned the postman away. They refused to accept the documents as a way to register their protest. Only one villager received it, just to keep a copy on record.

Now, the samiti is in hyperdrive, drumming up support among politicians and local leaders. A delegation of over 25 villagers met Devender Hans, Congress MLA from Guhla, and submitted a memorandum to him.

“If needed, we will go to the court with the villagers,” Hans told ThePrint.

Kulwant Bazigar, former BJP MLA from the same constituency, was equally staunch in his support for Theh Polar.

“We will not let the village move from here. I have also talked to the Chief Minister on this matter, and he said that these people are my own. Who allows one’s own people to be displaced?” he said.

Also Read: Encroachments, garbage, no facilities—Rakhigarhi has fallen prey to empty promises

A question of belonging

Just outside the village, work on a ghat leading to the seasonal Saraswati River is underway. Villagers pray at the local temple, which dates back to the 1960s.

Theh Polar’s location along the banks of the revered Saraswati has helped keep ancient lore alive. Villagers say this is where Ravana’s grandfather, the sage Pulastya Muni, did tapsasya to gain divine powers.

But more than anything else, Partition is the common thread running through Theh Polar’s history. Moti Ram, now 75, was born three years after his family fled Lyallpur in Pakistan and took refuge in Theh Polar. Soon, families from Multan, Sindh, and Amritsar followed.

“There was nothing here. It was an empty land. People built their houses wherever they found a place and made it habitable,” he said, sitting outside a general store. “ASI is coming to evict us from here after so many decades. Why were we not stopped when we came here?”

He’s visibly anxious. The fear of having to lose everything again haunts him.

In a neighbouring house, a family has kept all their documents ready—Aadhaar cards, ration cards, voter IDs—just in case they have to prove they belong here. Another villager, Raj Rani, 60, has a Rs 3 lakh bank loan she took to build a pucca house. As she watches her granddaughter play on her lap, she frets about the future.

“There used to be big pits in many parts of the village when I was a child. Often, children and even adults would fall into them,” she said. These were the remnants of past excavations. “But we filled it with soil and built houses.”

For the ‘new’ residents of Theh Polar, the past is best left buried.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Chutiya sarkar ka chutiya ASI department wants to get the villagers vacate without paying compensation and without making arrangement of alotment of land for housing and land for agricultural use ,also land for commercial use.