42-year-old Chennai-based quality engineer Venkatesh chases cyclones, rides out superstorms, and predicts the next heatwave or thunderstorm, all by peering into his crystal ball of weather maps and data sets on his screen. His 12,000-odd followers wait for the MasRainman’s forecast — the name Venkatesh goes by on Twitter and his Tamil YouTube channel for the farmers in the region.

He is among a small but growing community of citizen bloggers — students, stock brokers, scientists, salespersons — who have become some of the most reliable voices for forecasts. Warnings of above average temperatures in some places, drought in others, and record-breaking rains due to El Nino are some of the things these bloggers talk about on a daily basis. The democratisation of data sets, easy access to real-time information, and frequent extreme weather events have fueled a weather blogging revolution, especially since the 2020 global lockdown.

These weather seers, spread out across the country in urban and rural areas, are more consistent and frequent in their updates than official warnings, which are released only a limited number of times a day by the India Meteorological Department (IMD). Unlike the IMD, which covers large swathes of land, these regional weather bloggers like MasRainman focus on the hyperlocal.

“Heavy Rain Alert for #Vizag #Viziagaram and #Srikakulam for next 2-3 hours,” was MasRainman’s alert on 3 May with accompanying maps and charts. In another tweet, he gives weather details for Nanmangalam, a neighbourhood in Chennai.

To give an accurate and timely forecast, Venkatesh wakes up at 4.30 am, and scours his bookmarked websites for real-time data from weather models — algorithms that forecast the weather by processing data from weather sensors from national and international sources, before posting on his socials.

Citizen weather bloggers use international data sources and weather models such as Windy, Weatherbell, Meteoblue, Tropical Tidbits, and WeatherBug, spending anywhere from Rs 1,500 to Rs 4,000 per month for their data by themselves. Connected through WhatsApp groups, this motley but concerned band of weather enthusiasts are also known for calling attention to lack of infrastructure and hurdles with weather forecasting in India.

“The IMD has limited budget and manpower,” says 28-year-old Adarsh Gowda, a stock market trader and citizen weather blogger from Bengaluru. “So we can’t expect everything from them. We are trying to fill the gaps in disseminating information.”

Also read: Muslims, Yadavs, Paswans—the 26 murderers, rapists released with Anand Mohan in Bihar

Localised data

There are about 35-odd weather bloggers spread out across the country, with nearly 25 of them concentrated in the southern states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Some of the newer bloggers are school and college students with a keen interest in understanding weather sciences. They entered the online community after being cooped up at home during the pandemic, realising their newfound love for forecasting.

Some of the established citizen weather forecasters such as Pradeep John or Tamil Nadu Weatherman have over 400,000 followers on Twitter alone, and Srikanth, who goes by the name Chennaiyil Oru Mazhaikalam Chennai Rains on Twitter over 100,000 followers. The bloggers tend to have several hundreds or thousands of followers and readers on their blogs and YouTube channels as well.

Though they provide local and multilingual weather forecasts, they also release information for the rest of India, making them hugely popular even among people not from their native states.

“Officially, we get only standard updates like possibility of rain, partially cloudy, etc., and that’s it. But there are many other details that are available and can be provided, like which part of a state will get rain and with what intensity,” says Bengaluru-based software engineer and online weather blogger Vijay Anand alias Namma Vijay. It is these gaps in information that Indian weather trackers step in to fill.

Vijay has been an online weather blogger for a little less than a decade, but has been forecasting since childhood, having been at it now for nearly three decades.

“I developed an interest in this when I was a kid and saw weather forecasts in newspapers. So I started to learn from books and then started making forecasts for friends and family,” he says.

He found his audience when he migrated from WhatsApp to Twitter two years ago.

Today, he has over 4,000 followers and gets almost 20-30 messages and tweets a month from people asking for weather updates.

For local residents, people like Vijay are friendly neighbourhood experts. Some requests that strangers send their way include asking for weather updates for a region to decide whether to attend a wedding, how and where cyclones are moving for a particular state’s coast, which parts of a city could flood that day and whether there is a possibility of flight delays.

Adarsh’s fascination with weather forecasting was born out of self-preservation. He needed to figure out what time to leave his Bengaluru office to avoid rains and inevitable traffic snarls. That was in 2015. During the pandemic, he realised he could share information beyond his circle of friends and family, and signed up on Twitter as Bangalore Weatherman.

These bloggers have built a formidable reputation among citizens, having been consistently accurate in their measured forecasts and nowcasts for the most part. Even bureaucrats across the country follow the bloggers and privately ask them for information regularly, says Venkatesh.

Also read: One-year-old baby goes to Delhi High Court to ask tough questions on India’s maternity laws

The community

Some weather wizards don’t limit themselves to quick Twitter or Facebook updates,but put out detailed reports on their blogs. Some popular ones include Kea Weather, Vagaries of the Weather, Gujarat Weather (India’s first weather blog), and Weather of Kolkata. They offer quick and timely updates with scientific explanations for the weather phenomena along with satellite images, detailed explanations about weather phenomena, and important updates of risky conditions.

He and fellow experts with decades of experience also guide newcomers in understanding the nuances of forecasting.

“The weather bloggers come with a lot of knowledge, and they also understand the science of weather systems really well,” says Kirthiga SM, PhD scholar at IIT-Madras who builds local climate and weather models. She too started out sharing forecasts based on her models, initially with just family and friends and then on Twitter.

“There is a lot of disagreement among the bloggers and not everyone agrees on forecasts. That’s what makes the community trustworthy, and the reliable ones get identified quickly,” she says.

The community interacts on WhatsApp. There are multiple regional and national groups of amateur weather enthusiasts who often pass crucial information to each other.

Indian weather bloggers are not located in India alone. Many new up and coming bloggers who regularly forecast for Kerala live and work in Saudi Arabia and UAE.

However, the community is primarily male, a concern that everyone notes. The bloggers hope that as time goes by, more women enter the scene, and soon.

“There are lots of opportunities for women to enter this domain. All resources are available on the internet and everyone is very helpful,” says Kirthiga.

Also read: Young women are jumping into wells in Barmer. It’s a suicide epidemic

Infrastructure and doppler

Weather data is obtained at the various state IMDs from sensors across more than 745 Automatic Weather Stations (AWS) or Automatic Rain Gauge Stations (ARG) spread across the country, one roughly every 20-50 km. Data is also obtained from satellites globally. The ground equipment measure a number of parameters and transmit data every 15 minutes (or one minute when needed) to state IMDs, which then all transmit required data to IMD Pune. Pune processes the information and sends it to the central IMD Delhi, which in turn issues forecasts and warnings, which are then exactly translated into regional languages on state IMD websites.

Forecast data is obtained from weather model algorithms developed by academics and government scientists. IMD uses Indian models such as the National Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting (NCMRWF) model or the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM-Pune) earth system model.

Globally, the most accurate, detailed, and the best known ones are the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) and the American Global Forecast System (GFS). It’s these models that weather bloggers prefer to get their data from.

“The best bloggers use these two models, but don’t just stop there,” says Kirthiga. “They obtain data from multiple models, analyse and understand them, and through their experience working with such data are able to provide short to medium range forecasts that are helpful.”

Bloggers are also keenly aware of problems with infrastructure and gaps in data.

For example, there isn’t enough data about lightning, which seems to have increased in the past few years, says Adarsh.

Kirthiga brings up the lack of enough ocean sensors. “What is happening in the oceans is extremely important for framing what is happening on land, India being a peninsula,” she says.

However, it’s not just the oceans, the Indian landmass is also missing some key infrastructure, and many installed ones often fail.

“The Gopalpur radar in east Odisha always seems to have a glitch, and the Paradip radar keeps breaking down from technical issues,” says 32-year-old oceanography masters student and Odisha Weatherman Biswajit Sahoo, who has been blogging since 2013. He is one of the two prominent citizen bloggers from the state. “There is no radar coverage in western Odisha, and cyclone season is here.”

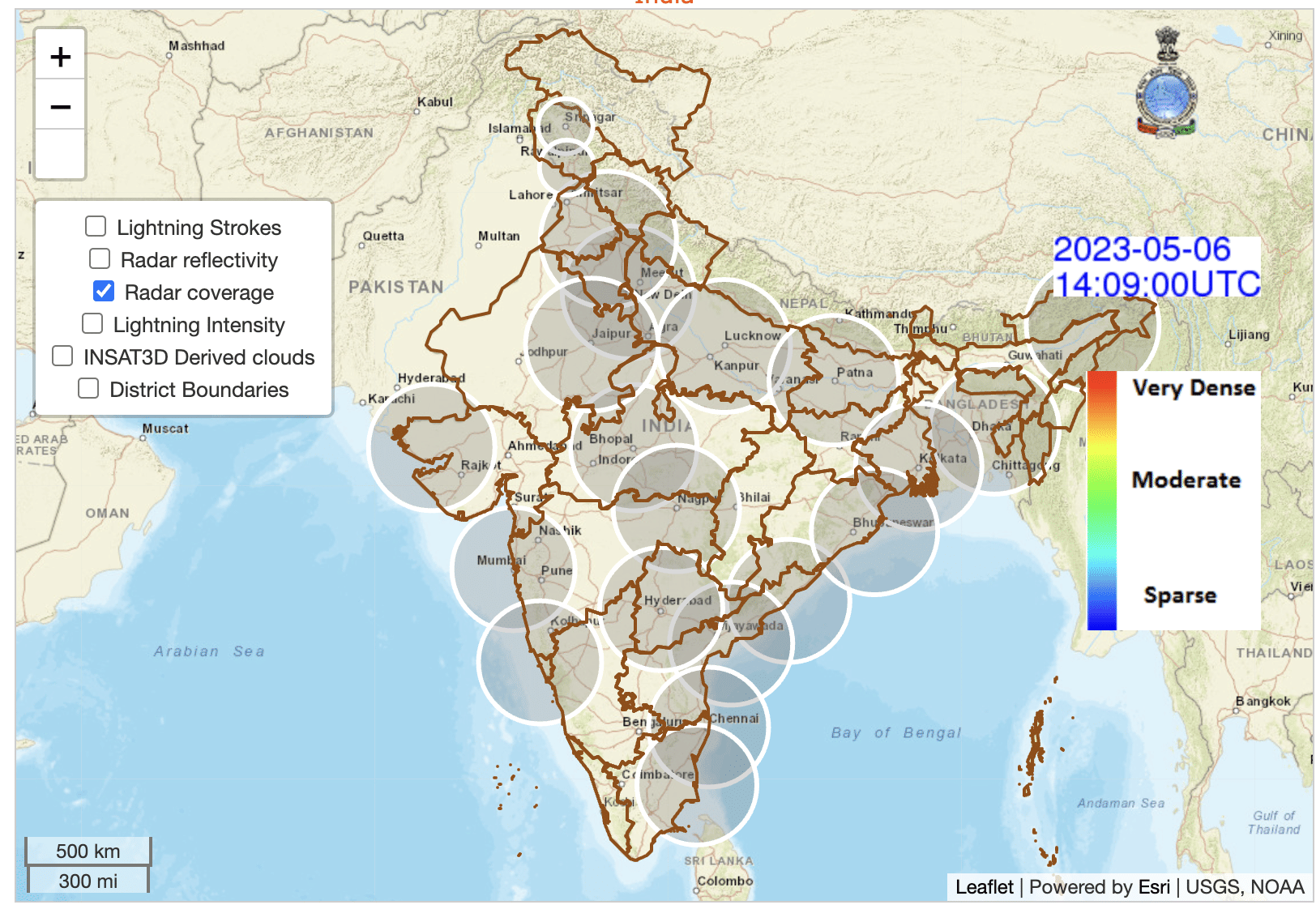

But it’s the shortage of doppler radars, and the lack of radar coverage over the entirety of the country, that elicits the strongest response from the community.

A doppler radar provides highly accurate measurements about how fast a weather system moves. By emitting beams of electromagnetic radiation, these remote sensing instruments can detect particles to track air motion, wind speed, rains, temperature, thunderstorms, hail, squalls, lightning, cyclones, cloud movements, and so on. Importantly, radars track precipitation, determine its motion and intensity, and identify its weather phenomenon.

Currently, there are 37 radars across the country, with low coverage in hilly regions, difficult terrain, and geopolitically contentious areas. States like Tamil Nadu, Goa and Uttar Pradesh have multiple radars that provide highly accurate information, with ample data.

“The Chennai radar is one of the best, German-built radars that provides extremely good quality data,” says Venkatesh. “In fact, since it came up, bloggers started learning all about cyclones, beginning 2008 or so, because data became very granular and accurate.”

In the last two years, dopplers have come up in Jammu and Uttarakhand. However, Karnataka and Rajasthan are the two largest states without a radar.

According to weather bloggers, this lack of key radar infrastructure affects the accuracy of forecasts. This is especially true for two large patches in Karnataka and Rajasthan that are completely outside the coverage zone of any radar. Parts of Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh are also outside of radar coverage, as is the state of Kerala. Odisha has two Doppler radars, but they cover only the eastern part of the state, says Biswajit.

All of these regions are prone to intense rains and most are prone to severe drought, affecting a large section of the Indian farming community.

“Karnataka receives the second-highest rainfall. Some of the wettest places in Western Ghats are here, and important interstate rivers originate or pass through the state,” says Vijay, who is one among several bloggers who have contacted or written to the authorities about this deficit. “It lacks the machinery for accurate weather information.”

Bloggers have written to the central government, IMD Delhi, the state government and the Karnataka IMD several times over the last decade. Promises of a radar have been made over the years, but none delivered.

In 2012, it was announced that Karnataka would be home to eight radars at a cost of Rs 128 crore, and that the entire state would be covered by December that year. Subsequently, in 2014, sites for the radar were identified. Even as late as last year, IMD authorities said “talks are underway to install” a radar in Bengaluru, but no update has been announced yet.

IMD’s director general Mrutyunjay Mohapatra says, “We are in the tendering process now. The radar will come up in two years.”

The cost of installing one radar is about Rs10 crore and maintenance is about Rs30 lakh per year, says Vijay. “It’s not that expensive, and we have no idea what the hold up is.”

Also read: Punjabi illegal migration to US relies on asylum letters. And one MP is doling them out

IMD and govt agencies

Bloggers and the general public have access to regional IMD data as well, which makes their localised forecasting and nowcasting extremely useful. And though there is room for improvement, the community is quick to acknowledge the importance of the IMD.

“Without the IMD, there will be no bloggers,” says Venkatesh. “India’s weather data is quite good, and we have one of the best cyclone prediction centres in the world.”

However, the central IMD at Delhi releases broader scale forecasts to keep general information to the public simple. Behind the scenes, at the state IMDs, there is a wealth of regional information that does not make it to the public through the agency. Bloggers are experts at navigating this data and providing useful information.

Many members of the citizen weather community suggest that IMD should work closely with other responsive authorities like the State Disaster Management Authority to disseminate timely warnings.

“Some state authorities are very responsive and efficient,” says Adarsh. “We also make use of the state’s disaster management authority’s apps.”

Mohapatra says that the IMD continually augments its organisational and modelling systems, and forecasting, and stresses that its main role is forecasting only.

“The forecasts go to all stakeholders. We have all the Dos and Don’ts in our information bulletins, but actions are expected to be taken by state authorities, municipal corporations, and NDMA. We are limited to only forecasts, which are done in a seamless manner.”

The weather bloggers have a huge advantage — members of the public can communicate with them directly through social media. On his handle, Weatherman Navdeeep Dahiya warns people of moderate to heavy rains in north and west Delhi. “Temperature anomaly likely to be 15°c below normal, insane!” he ends his detailed post. And when a user asks him about an update in the tricity, he responds immediately, “Showers possible later in the evening”.

Such a direct feedback system from the people on the ground doesn’t exist with IMD Delhi, and thus the agency would benefit from working with bloggers effectively, says Kirthiga.

“We are always open to collaboration,” says IMD’s Mohapatra. “Anyone who is interested can pull out IMD data. Bloggers’ job is not to issue forecasts. IMD’s job is to provide forecasts, and the bloggers then disseminate further.”

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)