Thursday’s SC ruling paves way for final hearing in Ayodhya land dispute case to begin. And a verdict may even be possible before the 2019 Lok Sabha polls.

New Delhi: The Supreme Court, in a majority 2-1 judgment, Thursday declined to refer its 1994 Ismail Faruqui judgment to a larger bench. The 1994 ruling — which allowed the Central government to acquire the disputed 2.77 acres, where the Babri Masjid stood before its demolition — held that praying in mosques is not an essential religious practice in Islam.

The bench, led by Chief Justice Dipak Misra, said the “law isn’t always logical” and that “the facts of the Faruqui case”, which was a land acquisition matter, does not apply to the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi case, which is a title suit.

Also read: Final hearing of Ayodhya Ram Mandir land dispute to start 5 months before Lok Sabha polls

Justice S. Abdul Nazeer, however, dissented from the majority view and said, “The contentious observations in Faruqui case have influenced the 2010 Allahabad High Court judgment.”

Justice Nazeer was referring to the high court verdict that directed a three-way partition of the disputed land in Ayodhya.

What’s the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi case all about?

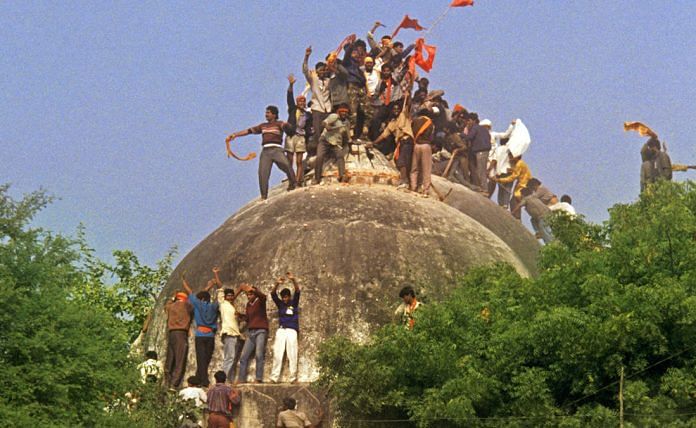

At the heart of it, the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi case is a property dispute. It involves the disputed land where the Babri Masjid, a 16th-century mosque once stood, before it was razed by kar sevaks on 6 December, 1992.

In 2010, the Allahabad High Court divided the disputed land into three equal parts between the petitioners — the Sunni Waqf Board, the Nirmohi Akhara and the deity, Ram Lalla.

The Supreme Court has stayed the Allahabad HC judgment.

The matter is politically contentious since the 2019 Lok Sabha polls are just a few months away.

What is the Ismail Faruqui judgment?

The 1994 judgment was in reference to a petition that challenged the government’s decision to acquire the disputed land. The Faruqui ruling allowed the Centre to acquire the disputed 2.77 acres, under the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya (ACAA) Act, 1993. The government had acquired a total land of 67.7 acres.

The three-judge bench, however, while holding that offering namaz (prayers) was an essential religious practice, said, “A mosque is not an essential part of the practice of the religion of Islam and namaz (prayer) by Muslims can be offered anywhere, even in the open”.

Why did the issue come up?

The top court was hearing a batch of appeals challenging the 2010 Allahabad High Court judgment, when the Muslim petitioners — represented by senior advocates Rajiv Dhavan and Raju Ramachandran among others — said the 1994 verdict was unfair to their case at hand.

They alleged that the 2010 Allahabad judgment was deeply influenced by the verdict passed in 1994, thereby leading to the three-way division of land.

The Hindu faction — represented by senior advocates like K. Parasaran, Additional Solicitor General (ASG) Tushar Mehta and others — said the petitioners were trying to delay the case by invoking Faruqui.

Also read: Photographers summoned for Babri trial worried about grainy memories of 1992 demolition

What does Thursday’s ruling mean for the case?

Since the apex court has refused to reconsider the 1994 verdict, arguments in the main Ayodhya title dispute case are set to restart from 29 October.

This may even ensure a final verdict being pronounced before the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, which are expected around April-May.

Out of general curiosity, I googled for the “Ismail Faruqui Judgement” that is mentioned in this article. I am copy-pasting the initial portions of the Order, only the first two points of it. You would notice that the order quotes from Jonathan Swift, and Swami Vivekananda. If the honorable judges were fond of citing quotations to push their argument, why didn’t they find a quotation from the Quran, which would be more relevant to the case? Anyway, I am no one to comment on the judges’ judgement, but I thought I would bring this to the attention of fellow readers of this article. The Order is a long one, I did glimpse at the whole, couldn’t understand much, but the word “Quran” wasn’t mentioned anywhere. Have a look:

——-

Dr. M. Ismail Faruqui Etc, Mohd. … vs Union Of India And Others on 24 October, 1994

Equivalent citations: AIR 1995 SC 605 A

Bench: M V Verma, G Ray, S Bharucha

ORDER

“1. We have just enough religion to make us hate, but not enough to make us love one another.” – Jonathan Swift

2. Swami Vivekananda said –

Religion is not in doctrines, in dogmas, nor in intellectual argumentation; it is being and becoming, it is realisation.

This thought comes to mind as we contemplate the roots of this controversy. Genesis of this dispute is traceable to erosion of some fundamental values of the plural commitments of our polity…”

——-

All religions say that God is everywhere. So in that sense, a place of worship is not “essential” for any religion! But the Quran does say that the Muslims should pray together in a mosque. When prophet Muhammad shifted base from Mecca to Medina, an event which is known as the Hijra, he constructed a mosque in Medina soon after arrival so the Muslims could pray there in congregation.