New Delhi: Once upon a time, a greedy woman lived in a village with her husband and her son Babu Lal. Idle and uninterested in getting a job, Babu Lal would spend his time roaming uselessly around the village and harassing a woman named Suman.

Babu Lal’s friend Cheema warned him that Suman was actually a ‘chudail‘ (witch), which he refused to believe. Thanks to Babu Lal’s relentless insistence, his parents spoke to Suman’s and the two were married.

The very next day, Babu Lal’s mother, upset that Suman hasn’t brought any dowry, dismissed her domestic help since she felt that from now on, Suman should do all the house work, leading to a fight. Soon, Babu Lal realised Suman really was a witch (by seeing her reflection in the mirror — scary blue face, dishevelled hair, the works) and ran to Cheema for help. Cheema picked up an idol of Hanuman and starts reciting mantras, and Suman was vanquished.

Called Patni Nikli Chudail (The Wife Turns Out To Be A Witch), this animated YouTube video by Dream Stories TV, simple and childlike in its style and narrative, features a deeply problematic portrayal of women and of a range of social issues (harassment, dowry, patriarchal notions of a woman’s role in the house, to name a few). Yet, it has received more than 34 million hits in less than a month.

And it’s not the only one. There are several animation companies with YouTube channels dedicated solely to these videos, which rack up views in tens of millions.

So, who is making these chudail videos, who is watching them and what do message they send to their audiences?

Move over, nagin movies, it’s all about YouTube’s chudail now

Neeraj Bhaskar, owner of Dream Stories TV, explains, “Before starting this YouTube channel, I did some background research and found that nowadays, more and more people like ghost- and supernatural-themed videos. So I started to make them. Chudail videos are getting so popular that a separate section has been created just for them — Dream Stories TV Adventure. It was created in January 2019 and as of now it has close to 5 lakh subscribers. The total number of views for all the videos pooled together is more than 104 million.”

My CartoonTV Hindi Stories’ Chudail Kal Aana (Part 1) has notched up 9.7 million views in six weeks (the second part, uploaded on 28 September, has almost 3 million). Best Buddies Stories & Rhymes, which has more than 5 lakh subscribers for its horror videos, has been uploading videos specifically with the keyword ‘chudail’ for the last three months. Bedtime Stories — KidLogics, with more than a million subscribers, has been making horror-themed videos for almost a year. However after the fast-emerging trend of chudail videos this channel has also switched tracks.

Dream Stories TV Adventure has a seven-member staff, of whom two are women. All of them are aged 22 to 32 years, and have studied animation. Bhaskar prepares the story and script himself. However, several channels also outsource the making of these videos, and Bhaskar explains the per-minute cost of such videos is between Rs 6,000 and 15000, including animation, voiceovers and more. Bhaskar reveals that he earns $1,000 per 10 million views. This entire business is being run on the basis of “pay for views”, he says, so if a particular keyword is minting money then it is often exploited to its core, until a new trend enters the market.

Also read: With swag and a London feel, Connaught Place is the adda for Delhi’s TikTok celebs

Men love chudail videos

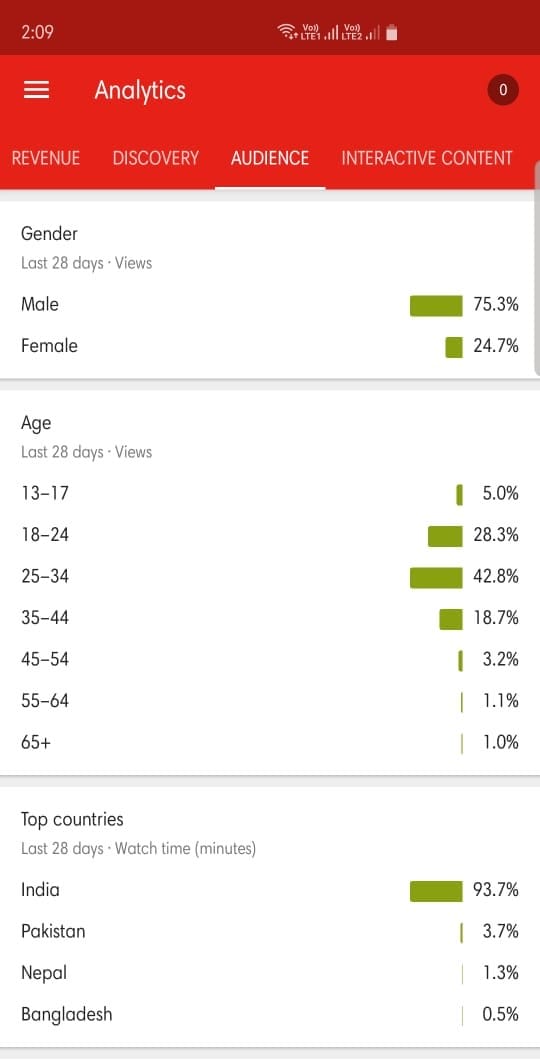

Interestingly, while many of the videos are tagged as “moral stories for kids”, the majority of the audience for this content is men in their 20s and 30s. Dream Stories TV’s Bhaskar shares that only 24.7 per cent of its audience consists of women, while men make up a whopping 75.3 per cent. The bulk of the audience, 42.8 per cent, is between 25 and 34 years old. KidLogics corroborates this, saying 50 per cent of its traffic comes from the 25-35 age group.

Bhaskar believes that a reason for this age demographic is that these are young parents who are showing these videos to their children. Plus, kids as young as three or four also now have a tendency to pick up their parents’ phones and know how to browse. Four-year-old Kush lives in Delhi’s Pinto Park and can easily type “chudail” in YouTube’s search bar. Kush’s mother Sonali tells ThePrint: “The soap operas being aired on TV were already ‘inspired’ by horror stories featuring witches and demons. Now, YouTube is also being flooded with chudail-themed videos. As a result, Kush keeps talking about Jai Hanuman and chudails all the time.”

On sexism, witch hunts and the message of these videos

Traditionally in much of Indian folklore, witches are presented as evil women who wander here and there to fulfil their bloodlust. In more familiar gatherings, the term ‘bloodsucking witch’ are also used to refer to wives in jokes about marriage.

Many of the chudail videos on YouTube also have deeply problematic stories or dialogues — about dowry, a woman’s role in her marital home, the way harassment is completely normalised and the way men are treated as entitled ‘Raja Betas‘.

Even in MyCartoonTv Hindi Stories’ two-part Chudail Kal Aana, in which the woman turns into a witch because she is wronged and killed, she is portrayed is needlessly vengeful, while justice is delivered to her by a male sage, who also gets to make a nice little speech at the end and be the hero of the piece.

On the other hand, popular culture is far kinder to male supernatural creatures. In Bollywood movies such as Paheli, Bhootnath Uncle and Chamatkar, male ghosts are presented as icons of the good that triumphs over evil.

Bhaskar tells ThePrint he’s been in the YouTube business for about four years now. “I have a six-year-old daughter. When I think about the stories for these videos, I always try to imagine that how my own daughter will react to such videos. That is why the witches in my stories are not that horrible or scary. In my videos I always portray victory for truth, so that the kids can differentiate between good and evil.”

When asked if he doesn’t see a problem with the depiction of women, he says, “Our videos don’t show the witch in a negative or dangerous way that will scare kids. And things like dowry, stalking do exist in our society.” How his daughter and many other kids will internalise the message of these videos is something he cannot say.

Geeta Shree, an acclaimed Hindi author and feminist, has recently launched a book titled Bhoot Khela, which portrays the human side of ghosts. Interestingly, in the stories featuring female ghosts, there is a glimpse of sisterhood where instead of scaring other women, they often come forward to help other women.

She recalls that while the correct Hindi feminine word for bhoot (ghost) is bhootni, there is no masculine equivalent for chudail. In her view, words like chudail and dayan (female demon) were cleverly crafted to portray women as ugly-faced, bloodsucking creatures. Kids growing up on these videos, she believes, will grow up with a misogynist idea of women, and this can have consequences in their adult life. She rues how market- and trend-based consumerism succeeds in selling a narrative with no consideration for ethics and social values.

Dr. Rajesh Sagar, a psychologist at AIIMS, says that it is parents’ duty to keep their kids away from such trends. The word chudail might generate an innocent curiosity in a child of four or five, but its impact can be felt for a long time.

India has seen several instances of women lynched by mobs who termed them as witches. According to the National Crime Records Bureau’s data, about 1700 women were murdered as on suspicion of witchcraft between 1991 to 2010, and there have been several instances even in the past four or five years. Some of the murders were also linked to property disputes.

When asked about the need for such videos given this context, KidLogics tells ThePrint that “These videos are made purely for the purpose of entertainment. Today chudail is trending, tomorrow it will be something else.” Bhaskar insists, “This kind of mob lynching is a complex issue, and it’s not right to connect it to an animated video on YouTube. They are two separate things.”

Also read: TikTok is giving birth to India’s new influencers — young men who cry, violently