A blinding white light periodically flashes in slow motion as a paparazzo repeatedly photographs Hollywood icon Marilyn Monroe. Two decades earlier, a young Marilyn, known by her birthname Norma Jeane Mortenson, had run away from her abusive mother after evading a murder attempt by forced drowning in the bathtub, while wildfires raged outside.

From the get-go, this juxtaposition between an infectious media love-in with your public persona and domestic abuse behind closed doors not only kicks off Netflix’s latest high-profile film release Blonde but also sums up its central theme.

However, this comes with a crucial caveat — this is an almost entirely fictionalised narrative adapted from a Joyce Carol Oates novel. It’s directed by New Zealand-born Australian filmmaker Andrew Dominik who boasts an impressive resume of thought-provoking crime dramas and a duo of acclaimed documentaries on Australian musician Nick Cave.

Subtlety be damned

To Dominik’s credit, Blonde subverts the usual humdrum biopic Oscar-bait methods by adapting an openly false story on real people and unabashedly skewering Norma Jeane’s abusers as well as Hollywood as a whole.

Be it her second husband, big shot film producers, the sons of fellow Hollywood icons, American President John F. Kennedy or the peripheral employees of the industry, Dominik takes aim and fires at each and every one of them for inflicting emotional, physical or sexual abuse on Norma Jeane till her final days.

And for a lengthy 167-minute film, it is surprisingly highly focused on this unflinching indictment of a misogynistic industry that simply sexualised her and seemingly never gave her constructive commentary on her primary skills as an actor.

But the overall question of executing this theme is far more complicated, as all the powerful sequences are also laced with long drawn-out scenes on Norma Jeane’s alluring beauty.

Instead of giving us more on her talent and on-set work, as he had done with an insiders’ look into Nick Cave’s recording studio alongside his personal tragedy, Dominik appears solely interested in these sources of Norma Jeane’s trauma and beats your head over with his disgust at the situation.

Perhaps that’s the fundamental problem with Dominik’s work and Oates’ before him — they take the uber-explicit Game of Thrones or Wolf of Wall Street approach in shoving the message down your throat, be it sexual violence with the former or greed with the latter.

The excess of the cycle of abuse is the point here, but by belabouring it 18 million times over nearly three hours instead of writing a more dynamic script, the end result is an unwieldy, self-indulgent slog rather than a powerful, unmissable product.

As a result, it is Dominik’s first real misstep in an illustrious career, as he failed to play to his strengths that were visible in his prior works.

Also read: Hillary Clinton’s Gutsy on Apple TV is a feel-good Hallmark card tribute to feminists

The upsides

Fortunately, Blonde is far from a total disaster, thanks largely to A+ acting from everyone involved as well as excellent choices made by Dominik and his team on the technical side of things.

Ana de Armas disappears into her portrayal of Norma Jeane/Marilyn — much like how Austin Butler did for Elvis Presley earlier this summer — and dispelled the pre-existing xenophobia surrounding her Cuban-Spanish accent as it is nowhere to be found here.

You completely buy into Norma Jeane’s frequent reliving of trauma and the impact on her mental health as well as her emotional dialogue deliveries at auditions and table-reads during the few such scenes in the film. In doing so, she rivals Michelle Williams’ Marilyn Monroe performance from a decade ago in My Week with Marilyn (2011).

De Armas is masterfully supported by heavyweights Bobby Canavale and Adrien Brody who have the thankless task of portraying the second and third husbands — retired baseball player Joe DiMaggio and playwright Arthur Miller.

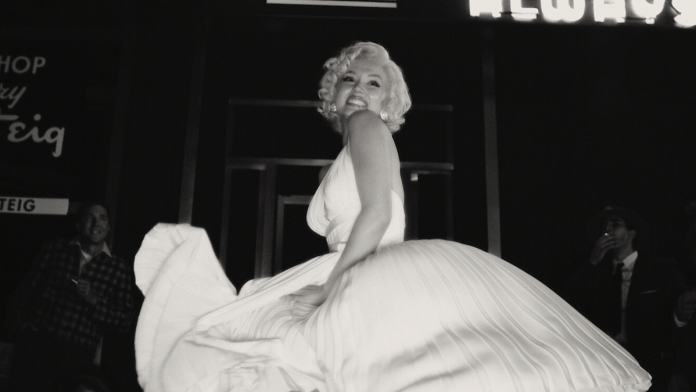

For all his writing faults here, Dominik excels with decision-making on the film’s colour palette, which transitions frequently yet seamlessly into black and white. Often, these are the best sequences in the film as well, such as Norma Jeane’s stage work with the Los Angeles Actors’ Circle or her first meeting with Joe DiMaggio.

These sequences also provide opportunities for cinematographer Chayse Irvin and score composers Nick Cave and Warren Ellis to shine as they add poetic elements of tragedy.

But there are only so many bells and whistles you can insert when the premise at its core is weak and less compelling than the real-life story. In its fictionalised focus, Blonde only partly does an effective job of critiquing Hollywood and instead adds to some of the harmful myths behind the tragedy of Marilyn Monroe.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)