Gumla/Ranchi: When the migrant women return to Jehan Gutwa before the harvest season, little girls from the village surround them. The women come bearing gifts and flaunt the English words that are now part of their vocabulary. They wear trendy clothes, talk confidently and tell stories of the grandeur of Noida malls, broad roads, 24×7 electricity, tap water, and comfortable mattresses.

The girls from this village in Jharkhand’s Gumla district are star-struck. They are fascinated by the stories of places they have seen only in movies and Instagram reels. Far from the drudgery of their lives, the cities with their tall, shiny buildings hold the promise of infinite happiness—utopias of plenty of food and enough money to buy pretty clothes.

But they’re unaware of the abuse. Nobody tells them how a 14-year-old domestic worker was beaten up so badly by her employers, a couple in Gurugram, that she had to be hospitalised. In villages like Jehan Gutwa, a daughter holds the promise of boosting the family’s income. The sons, after all, can only manage labour work in brick kilns of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

Often, neighbours and relatives sweet-talk children into leaving the village with them.

“We’re seeing a lot of cases where children leave for big cities for the glamour of city life they see on social media. They think their lives will be transformed if they reach Delhi or Mumbai,” said Ritu Kumari, incharge of a government-aided shelter home in Gumla district.

Girls as young as ten hold on to this dream when they empty their school bags, stuff them with clothes and hop on a train out of Jharkhand. The reality check is swift, and often brutal.

“I thought I’ll watch movies in the theatre and learn English after work. But madam never let me leave the house or gave me any money,” a girl who was recently rescued from a house in Delhi’s Saket colony said.

Rescued girls who return home are seen as a stain on the family and the village. ‘Dilli returns’ — as they are mockingly called — rarely talk about working without a weekly break, enduring verbal and physical abuse from the ‘madam’ or ‘sir’ of the house, or sleeping in a tiny space with other domestic workers.

Better and worse

Since the women earn more, men who stay behind or leave their villages to work as security guards or in brick kilns have come to accept that migrant labour work has better prospects for women.

“The job of a domestic worker is much better. It pays better too. I would happily wash dishes than lift heavy construction material on my back,” Sanjay Kumar of Phori village told ThePrint over the phone.

Women who migrate on their own volition earn good money and become the primary earning members of the house.

“In many instances, women work out of state while the men stay back and look after the household. The woman can earn up to Rs 20,000 a month and calls the shots in the house,” said Baidyanath Kumar, a child rights activist based in Ranchi.

This switch in conventional gender roles does not sit well within the community. “Village folk talk down to the stay-at-home husband and turn him against his wife, mock him for his apparent loss of manhood,” Kumar added.

And it’s this freedom that girls find attractive, which fuels their desperation to leave.

Also read: After Punjab, now Haryana youth fleeing to US–by any ‘donkey’ means possible

Delhi Express

A 13-year-old girl is visibly anxious as she sits next to a man she claims is her boyfriend on Platform Number 1 of Ranchi Railway Station. A train to Anand Vihar in Delhi is about to pull up.

But she has been spotted by Inspector Sunita Panna of the Railway Protection Force. Railway police officers in plain clothes patrol platforms to look for children travelling alone or are in the company of a suspicious person. If Panna hadn’t spotted the 13-year-old, she would have probably disappeared, crushed by the anonymity of big cities.

“I am going to Delhi to meet my parents,” she answers as the police question her. “I am going there to work,” she says next. An officer gently asks her if she knows where she’s going. The girl, who lives in Bhinjpur village in Gumla district, remains quiet.

“Whatever it is, it must be better than my village,” she whispers after some time.

The Delhi-bound train pulls out of the platform, but she’s not on it. The police didn’t let her go with the stranger.

But Panna’s hands are tied too. “Often the child is with a parent, or makes us talk to a parent. If we verify that they are going with their parents’ consent, then we have no mandate to stop them,” the officer said. It’s not trafficking.

Out-of-state migration in Jharkhand is the norm, and most take up labour-intensive jobs. The average per capita income in the state is Rs 75,000 per year, about Rs 6,200 a month, among the lowest in the country.

A 2019 Tata Institute of Social Sciences (Mumbai) study found that 10 per cent of out-of-state migration is among adolescents between 13-18 years. And 55 percent migrants belong to the Scheduled Tribes.

Gumla district with its rocky terrain offers little or no prospect of economic growth even in agriculture. The benefits of the green revolution haven’t reached here. Villagers only grow rice during monsoon season, and migrate after harvest in search of menial jobs, children included. Only 15 per cent of Jharkhand’s agricultural land has access to irrigation facilities.

In some villages of Bishunpur block, 4-5 children leave almost every month, says Gumla Child Welfare Committee member Dhananjay Mishra. Earning Rs 8,000-10,000 a month as a domestic worker in Delhi is seen as a good deal.

In this exodus, men, women and children can fall victims to traffickers or find themselves in situations they had not signed up for. Jharkhand recorded 49 cases of child trafficking, second highest in India after Kerala, according to NCRB 2021. The cases were filed under Section 370 (trafficking) and 370A (exploitation of trafficked persons) of the IPC. At the same time, the state also did not register any case under the Immoral Traffic Prevention Act.

Gumla sees the highest number of reported human trafficking cases, said a senior police officer who did not want to be named.

The political situation makes it worse. Some villages are not completely free of the Naxal influence. “Better to send your kid out of the village than let Naxals recruit them,” said Binod Kumar, a child rights activist in Gumla with NGO Vikas Bharti.

Also read: Jharkhand’s Santhals have just won a protest against an ancient death ritual—the 2.5 m shroud

It’s a trap

This flight for a better life rarely translates to independence or financial upliftment.

“But people are so desperate, they feel it’s better to sell the children than see them starve to death,” said activist Arpana Bara, a child trafficking survivor.

Under Section 3 of the Child and Adolescent Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, it is illegal for children between 14-18 years to take up “hazardous occupations”, including domestic work or at brick kilns—the destination of the majority of children.

“Representatives of ‘placement agencies’ offer Rs 2,000 per month to families of young girls and boys and take them to Delhi. These representatives earn up to Rs 30,000 per child,” said Binod. After some months, the brokers stop paying the families and the children never get the money.

From poverty, children are transported directly to big houses in posh areas of South Delhi, Gurugram, and Noida in the employment of wealthy, well-educated families. What happens behind closed doors occasionally makes news of children being physically and verbally abused or held captive make headlines.

“Families contact the police only when the money stops reaching them and they’re unable to contact the child,” Binod added.

In August last year, a 14-year-old girl who managed to escape her employers in Srinagar was found roaming the streets, begging strangers to lend her their phone.

“Please come save me, I am being raped,” she told her father in Santhali when she finally found a kind stranger who let her make a call. It was later learnt that she and another girl from her village Phori in Gumla district had allegedly been sent against their will and forced to work as domestic workers. No missing report was filed by their families.

“We were given Rs 19,000,” she recalled. Both girls said they worked in multi-storeyed palatial houses in the valley, with families who were “abusive”. “I was taken to a different location, held captive in a dark room for days, and raped repeatedly,” the girl told ThePrint. The case is under investigation.

Her friend’s experience was also traumatic. “Bhaiya used to touch me inappropriately while I mopped, broomed, and dusted furniture,” she said.

Today, both girls are back in their village. While the 14-year-old is living with her parents, her friend lives with a physically violent elder brother. Their parents are dead. She sleeps under a broken roof on floors layered with fresh cow dung.

With cases of abuse coming out in the media, a few villagers have started sending their children to southern states, which are considered safer.

“I have sent three of my daughters to work in Chennai. I will never send them to Delhi. But in Chennai they earn well,” said a 47-year-old man from Jehan Gutwa.

Also read: What reports on Indian women’s falling participation in labour force don’t tell you

Police’s failure

The lure of the big city has engendered a thriving placement agency network, especially in Delhi’s Punjabi Bagh and Shakurpur areas, according to activist Baidyanath.

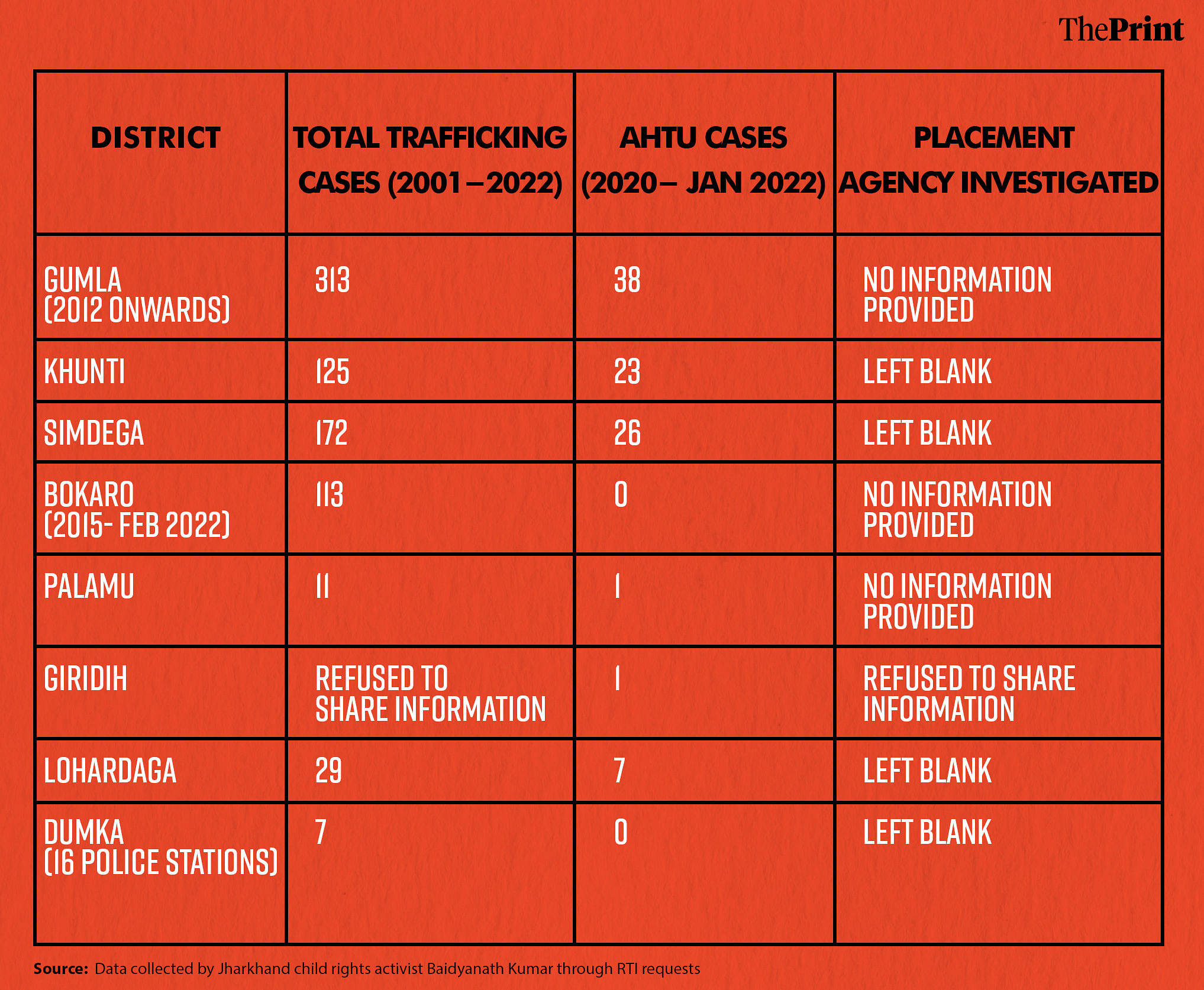

In January 2022, Baidyanath filed RTI requests to police in each district in Jharkhand seeking information on the number of FIRs registered between 2001-2022 under IPC Section 370, number of arrests made, cases registered at Anti Human Trafficking Units (AHTU), and details of placement agencies investigated by the police. So far, he has received responses from Superintendents of Police of seven districts.

A senior police officer told ThePrint that they can register FIRs only when people come forward to lodge complaints. “Families seldom file FIRs and it’s not possible for the police to keep track of every house in every village,” the officer said, requesting anonymity.

In 2017, Jharkhand’s then-Director General of Police issued an order telling the force to treat human trafficking as organised crime. Accordingly, the investigation has to link “the source transit and destination”. This meant that officers had to investigate how a person was trafficked, and link the transit to the destination — the placement agencies and the households employing the trafficked children.

However, according to RTI replies received by Baidyanath, none of the districts gave detailed identification of or action against placement agencies.

Dhananjay of Gumla Child Welfare Committee claims that the Hemant Soren government has been proactive, which has led to a “little bit of reduction” in trafficking.

“The AHTU has made a list of traffickers and has been arresting them. This has also made villagers fearful of sending their children away,” he said.

But the senior police officer cited above admitted failure on the part of law enforcement. “Placement agencies are a big failure in our investigation efforts. The problem is that once a kid is rescued, a chargesheet against one or two accused is filed and then everybody moves on. One has to remember that the police are also overworked. But we’re trying to move to a process where we see every case through,” he said.

One of the more high-profile ‘kingpins’ to be arrested was Panna Lal Mahto. He allegedly ran a human trafficking racket under the guise of placement agencies, traded 5,000 kids and made Rs 80 crore over the years. His was the last high-profile arrest, and the case is under trial.

The Vigilance and Monitoring Committees at the village level — comprising the sarpanch, two trafficking survivors aged 16-17 and a woman — are also responsible for preventing the trafficking. “We need to activate the committees. We are collaborating with the Panchayati Raj department to generate awareness about the child labour problem,” said Rajeshwari B, director, Jharkhand State Child Protection Society.

Also read: Haryana’s desperate bachelors bought wives. They turned out to be ‘loot-and-scoot’ brides

The rare hope

Little girls with pony tails and red ribbons run across the playground at Kasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalaya in Gumla. These are boarding schools where rescued girls are rehabilitated and educated for free.

“I like being at the hostel. The boys in the village used to harass me,” a girl at the school said.

Orphaned girls with no guardians are kept at shelter homes run by NGOs and aided by the government. Less than an hour’s drive from the school is one such home, which received 23 rescued girls between April 2022 and February 2023. Not all of them are victims of trafficking.

One of them is a 12-year-old who left her physically abusive brother to work with a family in Delhi. “After my mother passed away, my elder brother started abusing and beating me. I hated my life in the village,” she said. Even now, she insists she would rather work at the Delhi house than return home.

The steady stream of rescued minors is straining Jharkhand’s limited resources. On 17 February, RPF officer Panna prevented three girls—aged between 10 and 14 years—from boarding the trains to Delhi and Chennai. They were accompanied by a woman from their village.

Often when they are brought back or rescued from abusive employers, agents approach the families again. The 14-year-old rape survivor from Phori village said her family was contacted by ‘brokers from Delhi’.

“They offered good money but I refused to go. I will stay here and study hard to become a doctor,” she said. The 14-year-old now has a school to go to. “Although I don’t have any books.”