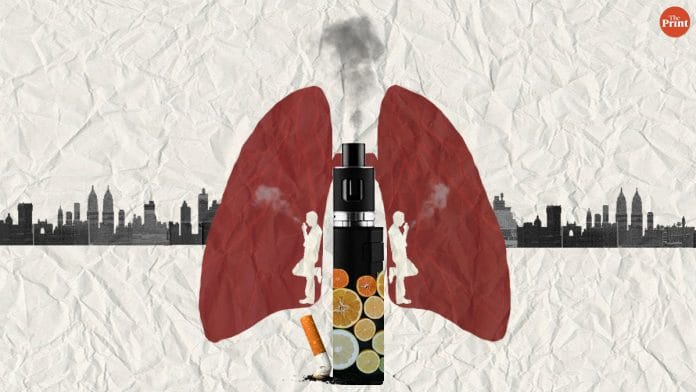

Three years ago, in a big boost to promote preventive healthcare, the Indian government banned electronic cigarettes. A plethora of evidence showed the devices were causing a new form of nicotine addiction even among non-smokers. With added flavours and attractive designs, adolescents were the soft targets.

But the ban could do little to curb the menace of vaping. A variety of nicotine-delivery devices are easily available at neighbourhood cigarette shops and an online search of ‘buy vape online’ throws up plenty of websites selling vapes in India.

Teenagers ThePrint spoke to said that vapes are ordered on WhatsApp groups active around college campuses at exorbitant prices. These devices are all the rage at pubs and after-school parties.

Parents, school teachers and anti-vaping activists are worried; two court cases filed last year have made the health ministry take note of poor enforcement of the ban on e-cigarettes. It has asked states to conduct month-long drives to implement the ban, and submit action taken reports. It also held a national review meeting last month and has reached out to law officers.

The first PIL was filed in Rajasthan in June 2022. A month later, the Jaipur Police conducted raids and booked five people under the Prohibition of Electronic Cigarettes (Production, Manufacture, Import, Export, Transport, Sale, Distribution, Storage, and Advertisement) Act 2019. The police commissioner also issued letters to the deputies to organise special drives and campaigns to implement the Act and take action against the offenders. They are also formulating methods to track online sales of vaping devices.

The Delhi High Court, which disposed of the second PIL, directed the state to “conduct more periodical checks in all localities in Delhi”, especially around schools and colleges.

Pro-vaping activists, on the other hand, are demanding revoking the ban and regulating the vaping devices instead.

Also read: Blanket vaping ban could do more harm than good to smokers, say experts

Enforcement and challenges

When offline classes at her private university at Greater Noida resumed in January last year after a long pandemic break, Priyansha Gupta, 22, a law student, saw many of her peers taking puffs from their vapes.

Her quest to find the source of the banned devices led her to file RTIs in her home state, Rajasthan. She found that no FIRs had been registered under the Act between 2019 and 2022. The state also did not conduct any raids to seize e-cigarettes, as per Section 6 of the law.

In June 2022, Gupta filed a PIL saying that the police, anti-smuggling unit and other enforcement agencies have failed to implement the ban on e-cigarettes.

“After my PIL, the police made five arrests in Jaipur, maybe just to show that they are taking action on this issue, when in three years they had made no arrests,” says Gupta.

A similar churn was taking place in Delhi as well. In November, advocate Shiv Vinayak Gupta wrote to 10 government departments and to Google, filed RTIs, cyber complaints, and a police complaint which led to a raid on a Defence Colony market shop where vapes and other linked devices worth Rs 20 lakh were seized.

“I found out that only two FIRs had been filed in Delhi since the ban. The ban has remained only on paper,” says Shiv Vinayak, adding that the Delhi shop that was raided is still allegedly selling vapes, though discreetly.

According to the Act, the police can take suo moto action and raid shops storing vapes. It also has the power to crack down on online sales. But lack of awareness among officers and accountability split among different agencies have made the ban ineffective, say public health experts.

“It’s an inter-ministerial issue. Online sales come under the electronics and IT ministry, commerce is under different ministries. This is why things are falling between the cracks. We need a body like the PMO that can reside over this inter-ministerial group. A blatant violation of the Act is happening,” says Monika Arora, vice-president research and health promotion, Public Health Foundation of India.

The sensitisation workshops for enforcement officers that happened for tobacco-related bans were also hampered due to pandemic lockdown, say experts.

“After the law came out, the [health] ministry laid down the procedure but with Covid lockdowns, there was no follow-up on the ground about seizures. Customs were sometimes seizing it where e-cigarettes were coming in as toys or some other material,” says Ranjeet Singh, the lawyer representing the government.

An enforcement officer told ThePrint that suo moto action to seize e-cigarettes is absent as there is no information about how deep-rooted the problem is in states.

He recommends a pan-India study, one that will shed light on the sale of the product, to what extent do minors purchase it and how.

“The states will then know the scale of violation. Currently, no one knows what the quantum of the sale is, who is purchasing, where these are sold. Right now, action is only taken when there is a complaint, which is rare,” says the officer. He adds that e-cigarettes are not considered a big issue yet because they are still seen as a tool to curb smoking.

But many in the judiciary as well as in the police aren’t even aware of vapes, as Gupta and Shiv Vinayak found out.

“The police booth is hardly 20 metres away from the Defence Colony shop where the raid happened. The police were not even aware what e-cigarettes are. They asked me for a copy of the Act,” says Shiv Vinayak in frustration.

The judge hearing Gupta’s case in Rajasthan also allegedly asked what e-cigarettes were.

Also read: Scientists are working hard to dismiss the anti-vaping argument

Catching up

On a recent trip abroad, S, a teenager, insisted that her mother, D, buy her a vape. S was attracted by the design and flavour and wanted one of her own. S had tried vaping with her friends at school before and her mother had weaned her off it after persistent effort. But the new vape would be S’ style quotient at school parties, she told her mother.

“You don’t want me to share others’ vapes and get an infection, do you?” S said to D, who ultimately gave in.

The e-cigarette heats a mixture of nicotine and flavours to create an aerosol for inhalation. It started making inroads into India about a decade ago. Since there is no tobacco, it was initially projected as a cessation device – just like nicotine gums and patches – by the pro-vaping industry.

Evidence soon started emerging of the harmful effects of vaping.

A white paper released by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) in May 2019 says that a cartridge in an e-cigarette contains as much nicotine as a pack of 20 cigarettes.

“The liquid vapourizing solutions also contain toxic chemicals and metals that have been demonstrated to be responsible for several adverse health effects, including cancers and diseases of the heart, lungs and brain,” notes the paper.

But to school-going children like S, the aggressive advertisement of vapes through social media platforms project these as less harmful than cigarettes.

In a yet-to-be published study conducted by Arora, based on interviews with 370 youth, she has identified 190 Instagram influencers who are promoting e-cigarettes. Her research also found that students from lower income backgrounds are pooling in money and sharing vapes.

The vaping industry has also innovated since it first launched. From the first set of vapes in the form of cigarettes and cigars, the devices now look like pods and flash drives, making it difficult to identify them as vapes at shops and even at homes. More than 460 different e-cigarette brands are available in over 7,700 flavours, as per the government records.

Also read: Number of non-smokers with lung cancer in north India is now same as smokers: New study

Why ban

Indian states started banning e-cigarettes in 2016. Punjab and Haryana were the first ones to ban it under the Poisons Act. By the time the Centre announced the ban in 2019, 16 states had already banned these electronic devices.

In September 2019, the Union Cabinet issued an ordinance banning Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS). Three months later, the health ministry introduced the Act, which bans all forms of production, sale, distribution, and advertisement, but not personal use.

While public health care activists are struggling to stop vaping devices from reaching adolescents, the pro-vaping lobby is pushing the device as a safer alternative to cigarettes.

Samrat Chowdhery, founder of Association of Vapers India, a consumer body of former smokers who switched to vaping, says that e-cigarettes have been the most effective means for him to quit smoking. The ban on the devices, he argues, should be lifted and vaping should be regulated.

“Nicotine by itself does not cause cancer. Vaping eliminates combustion. That itself makes it significantly less harmful than cigarettes. People should have the option to transition to a less harmful way of consuming nicotine,” says Chowdhery.

He adds that the use of e-cigarettes by teenagers cannot be the reason for denying 27 crore tobacco users a product that can potentially save their lives. The ban, he says, has pushed the vaping devices in the black market, making their access to teenagers easier.

In the courts, however, the need for a ban is reimposed. While the Delhi case was disposed of after directions to the enforcement agencies, the Rajasthan case is still on.

Meanwhile, the schools and parents are firefighting this menace. Schools are appointing monitors to check if children are carrying vapes and worried parents are looking for solutions to keep their children away from this ‘trend’ that is spreading like an epidemic.

The teenager S now owns an imported vape, but the device stays with D under strict supervision. It can only be taken out on special parties where it can be flaunted.

(Edited by Prashant)