New Delhi: If there was any doubt before, there is room for very little now — the confident, calculated steps of the Narendra Modi government to control the narrative around Jammu and Kashmir have been effectively ruffled by the foreign media.

External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar confirmed as much last week when he unambiguously identified “the English-speaking liberal media [in the West]” as being New Delhi’s biggest challenge in explaining its decision to repeal Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir to diplomats and foreign administrations.

At a gathering of American businesses under the US-India Strategic Partnership Forum (USISPF), Jaishankar said the US media was not aware of the fact that Article 370 was a temporary provision of the Indian Constitution, and were “ideological in their reporting” of it.

But even before Jaishankar’s remarks, it was obvious that foreign media coverage of Kashmir had become a thorn in the government’s side, chipping away at Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s concerted efforts to present himself as a formidable leader of the world’s largest democracy.

“India’s image has gained global prominence and the world expects our country to play a leading role in resolving international problems,” the Prime Minister told BJP workers in Ahmedabad on 2 October, shortly after returning from the ‘Howdy, Modi!’ event in Houston, Texas.

The foreign press on Kashmir

Since 5 August, the day the Modi government scrapped Article 370, the move has been labelled the “darkest day” (Al Jazeera), “a shock decision” (Bloomberg), and the “revocation of Kashmir’s limited autonomy” (Los Angeles Times).

On the day Modi spoke in Ahmedabad, Al Jazeera published a report about ‘Depressed, frightened’ minors held in the Kashmir crackdown.

The New York Times also published an editorial, criticising Modi for saying in Houston “that revoking the constitutional clause on Kashmiri autonomy meant ‘people there have got equal rights’ with other Indians now”.

“That’s an absurd assertion to make about a state in the world’s largest democracy that’s essentially under martial law,” NYT asserted.

Four days later, a high-level US Congressional delegation, comprising senators Chris Van Hollen and Maggie Hassan and US Ambassador to Pakistan Paul Jones, visited Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. Hollen had been previously denied entry into Jammu and Kashmir by India, citing safety concerns, when he “wanted to see first-hand what was happening”.

More heartbreaking news: https://t.co/syEmc12Hjg

But it leaves bhakts unmoved. So let's reframe the issue: Does our Govt understand how much damage such reports are doing to India abroad? Can it seriously assert that our international image has improved under their tenure?

— Shashi Tharoor (@ShashiTharoor) October 7, 2019

Reports in The New York Times (US), The Guardian (UK), Al Jazeera (Qatar) and South China Morning Post (Hong Kong), relying on local Kashmiri stringers to be their eyes and ears in the Valley (given that foreign correspondents have been denied free access), have focused significantly on alleged human rights violations in Kashmir.

These include reporting on pellet gun victims, torture, arbitrarily detained leaders and children, loss of livelihood, and the wide-spread ramifications of a communication blackout.

Countries like Japan, Australia, Canada, and most nations in India’s neighbourhood, barring Pakistan, that rely on news agencies (AP, AFP, Reuters) also reflect the criticism evident in the original reportage.

Editorials, encapsulating the formal position of a publication, were published by NYT, Washington Post, LA Times, Bloomberg (US), South China Morning Post (Hong Kong), Global Times (China), Financial Times and The Guardian (UK). All condemned India’s move.

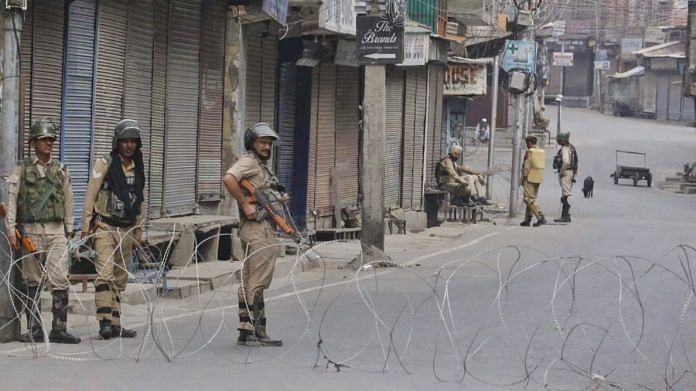

Further, photographs from Reuters, AFP and AP were revealing — deserted streets and closed shutters flanked solely by the military and paramilitary forces were a favourite with publications, and NYT’s collated photo report showed protesters mid-struggle with the security forces, and people struggling to leave the state with ticket windows crammed.

“For the foreign press, Kashmir is both a conflict zone, and disputed territory, and it covers it as such. After Kashmir’s change of status, they think it is their job to capture protests, not to pander to the Indian government’s sensitivities,” Sevanti Ninan, media commentator and former editor of the media website TheHoot.org, told ThePrint.

Also read: How foreign media has covered Kashmir crisis — and run foul of Modi govt

Fault lines

The fault lines between the foreign media’s coverage and the aims of the government were visible as far back as 9 August, less than a week after Union Home Minister Amit Shah announced the move in the Rajya Sabha.

Al Jazeera published a video on the first Friday after the move, which claimed that Indian troops had opened fire and used tear gas on Kashmiri protesters in Soura, Srinagar. The BBC (UK) followed. Almost immediately, the Ministry of Home Affairs was calling these news reports “completely fabricated & incorrect”.

A news report originally published in Reuters and appeared in Dawn claims there was a protest involving 10000 people in Srinagar.

This is completely fabricated & incorrect. There have been a few stray protests in Srinagar/Baramulla and none involved a crowd of more than 20 ppl.

— Spokesperson, Ministry of Home Affairs (@PIBHomeAffairs) August 10, 2019

Alt News, a fact-checking platform, confirmed that the protest videos were indeed authentic, although it was “unable to independently verify” whether any live rounds were fired by security forces.

While the MHA, three days after its initial statement, admitted that some “miscreants mingled with people returning home after prayers”, it categorically denies any live firing till today.

Law enforcement authorities showed restraint and tried to maintain law & order situation. It is reiterated that no bullets have been fired in #JammuAndKashmir since the development related to #Article370@diprjk @JmuKmrPolice

— Spokesperson, Ministry of Home Affairs (@PIBHomeAffairs) August 13, 2019

The BBC defended its coverage in an official statement, but the tone of the conversation between India and the foreign press had been set.

This wasn’t the first time that the BBC locked horns with the Indian establishment. The broadcaster was expelled from the country for two years in 1970 for telecasting two of Louis Malle’s documentary films — Calcutta and Phantom India — that “caused outrage amongst the Indian diaspora in Britain and with the Indian government, for what were perceived as prejudicial and negative depictions.”

“There’s always been extreme sensitivity about the foreign press in India,” Mark Tully, the BBC’s former chief of bureau in New Delhi for 20 years, told ThePrint. “It used to be particularly acute with regards to the British press for a number of reasons — because the BBC was so widely listened to in this country, the old hate-love-hate relationship wherein we were called colonial agents and such, and also because the Indian diaspora was so vocal back in Britain.”

“There’s a great desire for India to be seen as an emerging global leader,” he said.

The Western press, historically pro-democracy, were also extremely critical of Indira Gandhi’s imposition of The Emergency in 1975, writing dispatches despite hostility and threats to their safety. Seven foreign correspondents were expelled from the country, while another 29 were banned from entering.

International spotlight

A month after the scrapping of Article 370, as reports of human rights violations, a seemingly ceaseless communication lockdown and an increasing number of detentions in Kashmir continued to flood a host of international news platforms, world leaders began to take notice.

From Bernie Sanders, the frontrunner in the Democratic presidential race in the US, calling for a UN-backed peaceful resolution to UK Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn asking for “international intervention”, leaders across political and geographical lines were showing critical scepticism about the Indian government’s official narrative.

The situation in Kashmir is deeply disturbing. Human rights abuses taking place are unacceptable. The rights of the Kashmiri people must be respected and UN resolutions implemented.

— Jeremy Corbyn (@jeremycorbyn) August 11, 2019

Swedish deputy PM Margot Wallstrom also publicly criticised the decision.

By the end of September, 14 US congressmen, including one Republican, collectively issued a statement to PM Modi “urging (him) to lift the communications blackout and address the ongoing humanitarian concerns”. More recently, six others wrote to the Indian Ambassador to the US, Harsh Vardhan Shringla, stating that there was an evident discrepancy between the Indian government’s official line and the version of Kashmir being told to them by their constituents.

While I understand India has legitimate security concerns, I am disturbed by its restrictions on communications and movement within Jammu and Kashmir. I hope India will live up to its democratic principles by allowing freedom of press, information, and political participation. https://t.co/5xlWTE6ANu

— Mark Warner (@MarkWarner) October 8, 2019

The Strasbourg-based European Parliament also debated the ‘Kashmir issue’ for the first time in 11 years in September.

‘Liberal bias’

Vijay Chauthaiwale, the person in-charge of the BJP’s foreign affairs department, blamed the liberal bias against the party for the bad press.

“Look, there has always been a liberal bias against the BJP, especially by a section of the Western press, and to an extent, it is okay with us,” he said. “But what’s surprising is to somehow suppress the other side of the opinion, which is not conducive to free and ethical journalism. For example, many Kashmiri Pandits have written to the New York Times, but none of their opinions has appeared so far.”

At least one such opinion did make it to the NYT — ‘We Never Moved Back to Kashmir, Because We Couldn’t’ by writer and filmmaker Priyanka Mattoo, published on 12 September.

On 28 August, the news organisation also carried two letters by readers — “One reader condemns India’s moves as repressive, while another (written by a Kashmiri Pandit Hindu American) is hopeful about Kashmir’s future.”

The paper also published an op-ed piece by Ambassador Shringla, titled ‘India Is Building a More Prosperous Kashmir’, on 19 September.

“But look how soon the rejoinders came for so many of these,” Chauthaiwale said.

“They were far softer and less critical on Manmohan Singh; the UPA’s corruption scandals, inefficiency and decision-making paralysis rarely got this much coverage,” he said, adding that “even in 2014, The Economist had endorsed Rahul Gandhi”.

In contrast, during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the foreign media was less than friendly to PM Modi, described as “India’s Divider In Chief” by TIME magazine on its May 2019 cover.

As the BJP strutted back to power with an even bigger mandate than 2014, AP chose to describe Modi as a “charismatic but polarising” figure, while NYT qualified his victory as being aided by a “mix of brawny Hindu nationalism, populist humility and grand gestures for the poor”.

“I think Narendra Modi was criticised even after Gujarat, so it gave him a bad start with the foreign press,” Tully said, adding that while he’s wary of generalising the foreign press’ positions, “Hindu majoritarianism is not something that the Western press likes very much”.

In an opinion piece for Firstpost, Rajiv Tuli, state executive member of the RSS in Delhi, termed the foreign media’s coverage of Kashmir as “sensational misreporting” that “exposes their bias against India”.

But as Britta Petersen, author and former South Asia Correspondent of the Financial Times Deutschland in India, pointed out: “When Indians talks about ‘the Western media’ or ‘the foreign press’, they actually mean English and American media. Almost nobody ever reads German, French, Italian, Spanish or Scandinavian media.”

She added: “It is totally different in my own country (Germany), where the topic of Kashmir disappeared from the media after a few days. Having said that, India is a democracy and must be prepared for uncomfortable questions when it does things that democracies usually don’t do, such as putting political leaders behind bars and shutting down communications for weeks.”

Also read: Foreign media images seem doctored, haven’t tortured anyone in Kashmir: Indian Army chief

Kashmir, an ‘extraordinary newsgathering environment’

In an official statement to ThePrint, the BBC, through the BBC World Service’s Head of Indian Languages Rupa Jha, noted the “extraordinary newsgathering environment created by the absence of communications” in Kashmir.

“Balance is at the heart of our journalism, and our reports from Kashmir have unfailingly carried the positions of all sides of the story… Our reports…include interviews and accounts from BJP MPs Rakesh Sinha and Jay Panda, former J&K Deputy Chief Minister Nirmal Singh, ORF Fellow Ashok Malik, retired Indian Army General D.S. Hooda and others,” Jha wrote.

The Washington Post also said it stands by its reporters. “The Post’s coverage of India’s actions in Kashmir since the 5 August crackdown has been fair, accurate and comprehensive — at a time when India has imposed tight restrictions on the flow of information,” it said in an official statement to ThePrint. “We urge the Indian government to grant foreign correspondents access to Kashmir.”

S. Venkat Narayan, president of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of South Asia, also said denying foreign journalists physical access to Kashmir “has resulted in the perception that there is something to hide”.

“Keeping the foreign media in the dark completely, even two and a half months later, does not reflect very well on the world’s largest democracy and the freedom of the press,” Narayan said.

MEA and the failure of India’s PR project

For Wajahat Habibullah, former chairperson of the National Commission for Minorities, the government’s anxiety surrounding the internationalisation of Kashmir lacks self-reflection.

“The Kashmir issue had fallen off the international desk for many years now,” he said. “But if you’re going to take action that makes something an international issue and then say that ‘no, it shouldn’t be one’… That’s hardly the way out.

“What’s the point of the MEA? To be a communicator between the government of India and the world,” he continued. “Now if it’s come back, whose fault is it? Jaishankar would be well in the know of this, because he’s spent his career in the foreign service; he’s spent his career, like all (IFS) diplomats, in essentially justifying India’s stand and to gain respect for India amongst foreign nations.

“So, saying that ‘the media is doing this’ and ‘the (US) Congress is doing this’, because you have failed in your job… What is the purpose of blaming everyone else?” Habibullah asked.

Brahma Chellaney, noted author and international geostrategy expert, said the internationalisation of Kashmir wasn’t unprecedented — citing the Kargil war, the IC-814 hijacking and the Balakot air strike in February as examples. He said “factual distortions are obvious in many foreign reports”, but added that India’s bad press abroad was “a larger failure of the Indian government in not paying enough attention to media relations”.

“Media relations have been poor under successive governments — the tenure of Manmohan Singh also shows that, but the Modi government has an anti-elite bias, an anti-elite standing, if not an anti-elite government,” Chellaney said, adding that the MEA’s formal structure and the lack of official spokespersons in the PMO had made it anything but easy for journalists to get quotes or clarifications.

Chellaney was one of the few Indian voices arguing for the Indian side who was published in an international syndicate; his 2 September opinion piece ‘Myths of Kashmir’ was picked up by over 100 newspapers abroad, he said.

“There are very few Indians that are proactively writing on international issues. It’s like global discourse has been surrendered by Indians to the Anglo-Saxon group. Indians only write about Indians, but the world or even Asia, you leave it to the others to pontificate on those issues. J&K is just the latest example,” he said.

Also read: BBC to New York Times – Why Indian governments have always been wary of foreign press

(This report has been updated to accurately attribute comments to the Ministry of Home Affairs instead of the Ministry of External Affairs. The error is regretted.)

Al Jazeera is NOT liberal. It’s the mouthpiece of the Islamic right and far-right. (eg. bin Laden interview)

Give a large defence order to USA and they will be quiet. And UK labour party will never be in power. It is a part which gets Muslim votes as most of them live on doles and labour party is party of lazy idiots. Boris Johnson does not give a damn. And most Indians vote conservatives.

Many newspapers have criticised the Chinese for their treatment of their ethnic Muslims. Do they care?

Israel has been criticised for its treatment of Palestinians and selective killings of Iranian scientists. Do they care?

Myanmar has been criticised by foreign media when it kicked out all the Rohingyas. A small country like Myanmar does not care a bit.

Why should India care?

So what should India do? Hand over the Kashmir on a plate to Pakistan?

Bhai… Thora relax karo. Woh apna kaam kar raha hai tum bhi apna kaam karo.