Ankit* escapes his stifling, homophobic parents, abusive neighbours and school friends for a few hours every day when he goes to his college in Delhi University. That is the only time he gets to dangle beautiful bead necklaces around his neck and wear shiny rings on his slender fingers. He can truly be himself then.

But now, college life is also closing in on him.

Ankit, who identifies as queer, is a second-year student of Sri Guru Gobind Singh College of Commerce (SGGCC). For the last two years, colleges across Delhi University are turning into a battlefield for queer students. At the heart of it is a demand for officially recognised queer collectives, a safe space for ideas, events and conversations – much like women’s studies centre and debating, drama, dance and film societies in colleges.

Many colleges are pushing back. Students’ multiple memorandums to the college administration, protests, and files pushed through the faculty members have been gathering dust at the principals’ offices. Inside campuses, ThePrint has learnt, the demands of queer students in most colleges are met with resistance, ignorance, indifference, and even threats by the college authorities.

“As queer-trans people we have collective trauma of being alienated from the society, from our own family, for not being accepted. So, the entire world seems like an unsafe place for us. We have to constantly hold up our walls to make sure no one is coming to harm us. That is why a queer collective in college, where we don’t have to fight against anything and we can just be ourselves, is needed,” says Geeta*, a student from Hindu college.

College life, which typically represents freedom and fearlessness for the young, is especially critical for queer students who escape their families and schools for the first time. The campus acts as a portal to a life where they can safely come out and embrace their identities. But harassment, micro-aggressions and even suicides are turning campuses into sites of trauma.

In college canteens and classrooms, in festivals and events, the queer identity is overlooked, neglected, and dismissed by the faculty, peers and the administration, they claim.

Queer students are warding off daily comments on their looks, wrong pronouns, hearing their deadnames (names assigned at birth) and consuming homophobic misinformation on informal social media groups linked to their colleges.

ThePrint reached out to the principles of multiple colleges. Only Jatinder Bir Singh, principal of SGGCC, responded. He explained that there is a moratorium on the new societies (or collectives) since the college already has 40 clubs and societies. None of the other colleges responded to detailed queries sent by ThePrint.

Also read: Not woke on same-sex relationships, says Madras HC judge, wants ‘psycho-education’ session

The struggle to be seen

After nearly three months’ wait, Arnab Adhikari, a second-year student of Zakir Husain Delhi College, was called for a meeting by the gender sensitisation committee. His memorandum to the principal’s office for a queer collective was finally moving forward. He said he felt a tug of hope. But his happiness dissipated as soon as he entered the meeting room.

The attitude of the five faculty members sitting across him could be captured by one word – hostile. They asked him to keep his phone aside, and on silent mode. And a barrage of accusations followed.

“The committee members said that I am polluting the college and bringing a negative impact on its culture by demanding a queer collective. They accused me of spreading propaganda and said that I could be suspended,” said Arnab, the president of the college’s unrecognised queer collective.

The committee members allegedly told Arnab that if they acknowledge this “nonsense” (of forming a queer collective), then their college’s funding might stop. When Arnab didn’t budge from his demand, they allegedly said theirs is a religious minority college and accepting a queer collective might bring backlash from the Muslim community.

A popular student of the college, Arnab, in less than a year, had more than 80 students, across courses and religious minorities, supporting his cause for a queer collective on campus. His proposal to the management was simple: provide a platform to queer students where they can hold seminars and events around queerness.

The rebuttal from the gender sensitisation committee members crushed him. More than half the members supporting him disassociated themselves from the collective for fear of being suspended and their parents finding out.

Arnab’s brush with the management, however, didn’t end there. On 15 July, the gender sensitisation committee organised a seminar on ‘creating awareness on LGBT issue’, without any representation of queer persons. And it backfired. It also made Arnab’s resolve to get a queer collective on campus stronger.

The presentation described Q in LGBTQ as: “the gender identity is different in some way that is not normal, not heterosexual, something different”.

When Arnab objected, he was allegedly asked to keep quiet and leave the room.

“The organisers said they are learning to acknowledge the ‘abnormalities’ of people. They used wrong pronouns (like using ‘she’, ‘her’ for a person born a female, but doesn’t align with that identity). When I asked questions after the presentation, they said I am thinking too much,” he said.

His last letter to the principal requesting a queer collective, sent in August, has received no response yet. The principal’s office of Zakir Husain Delhi College did not respond to questions from ThePrint.

Similar requests for recognising queer collectives in other colleges are also either stonewalled or dismissed entirely.

Also read: Jamali Kamali, hijron ka khanqah, Sarmad’s tomb — Delhi history’s safe spaces for LGBTQ

Queerness, a ‘threat’

The queer collective at Jesus and Mary College (JMC) in south campus was started informally in 2018. Students began holding meetings and sharing their experiences, but were allegedly asked to keep it outside the campus.

“The members of the collective were told that they can’t do these “political things” in college. They were told that their parents will be called,” said Priya*, a queer student at JMC.

Students were allegedly threatened with detentions, given the similar alibi as Zakir Husain College that it was a religious minority college and were put on a spot with questions like, “do you think your parents would approve of these western ideas? This is against our social structure.”

Queerness, students at JMC said, is seen as a threat by the management.

By 2020, the JMC queer collective started demanding recognition from the authorities. But it never heard back. While other societies at JMC, such as the finance cell by the commerce department, were approved around the same time, the queer collective wasn’t, students claim.

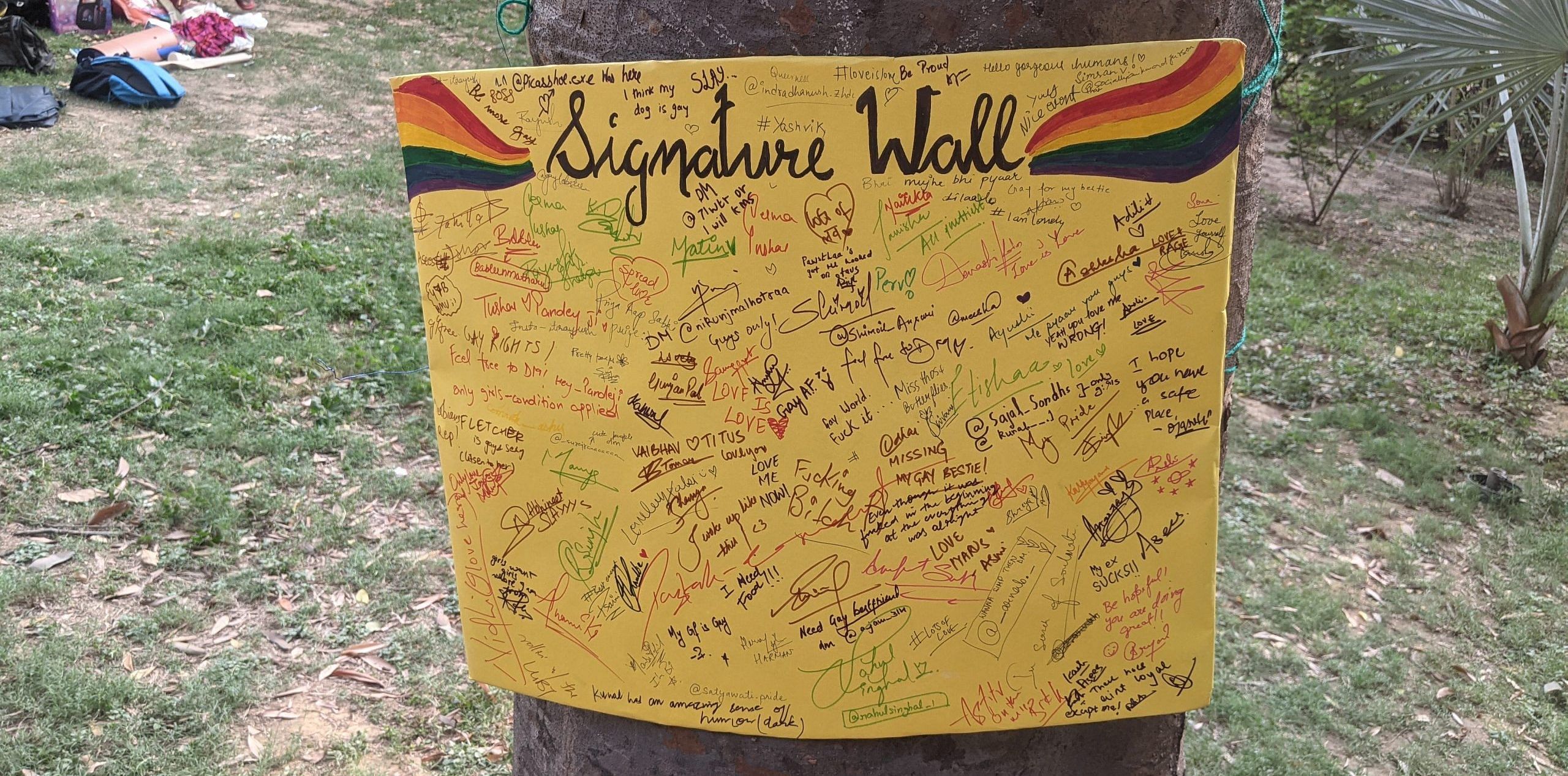

Unable to understand what they were doing wrong, JMC students reached out to queer collectives across north and south campuses to understand how their proposals can be made stronger. They held a signature campaign on campus and gathered support from more than 500 students. They submitted a fresh proposal in September to the principal. But that also went into a blackhole.

“Each time we checked, we were told that the principal is busy,” Priya said.

Fed up of the wait, the students decided to silently protest. For two weeks, every day, a group would just sit outside the principal’s office. When the principal finally invited them in, she allegedly said that she has no authority to sanction such a collective, said Priya.

The principal’s office of JMC did not respond to questions from ThePrint.

Also read: Dabur Fem’s ad plays on fairness obsession. But it got Indians talking about LGBTQ at least

A lonely fight for students

Two years ago, at SGGCC, when Nikhil*, then a fresher, reached out to the authorities with the proposal for a queer collective, he was allegedly asked for a list of queer students on campus. Calling it unethical, as many queer people are closeted, he did not submit the list. The second time, the students found a professor to be their collective’s convenor. But that professor was never seen again in college, says Nikhil. Such is the fear.

To mark their protest, the queer students of SGGCC came up with an innovative idea. They left tiny chits of papers in toilets and canteen, saying in Hindi: ‘You can see this tiny piece of paper, but you can’t see the homophobia in college?’

“Everybody saw that chit,” says Ankit.

The trick was a rage. On Instagram, the reel on these chits had over 10,000 views. But instead of addressing the homophobia on campus, the chits were torn off and the matter hushed up.

SGGCC principal dismissed the need for an independent queer collective. “In other colleges of India, I have found only a few societies doing a multitude of events. For example, NSS can do all social and awareness programmes and one doesn’t need a separate club for doing identified work. Queer group can do events under the umbrella of NSS,” Jatinder Bir Singh said.

NSS, or National Service Scheme, is a public service programme conducted by the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports in colleges. More societies and clubs in the college means more functions and hence more financial requirement, he added.

In many other colleges, the queer students are constantly asked to collaborate with the older, established women’s groups or gender societies, most of which have no representation of queer students or are ignorant about queer issues. The two cannot be easily conflated, students say.

Geeta from the Hindu College told ThePrint that their multiple letters to the principal’s office either go missing or the principal doesn’t bother to see them.

“Now we have decided to not seek recognition. The queer-trans people in the college are frankly exhausted. They don’t have the fighting spirit left. They just want a space where they can relax and feel comfortable and just be there for each other,” she said.

In this fight for inclusivity on campuses, the queer students, unfortunately, are alone. Those who step up to support are penalised in multiple ways.

A professor, speaking on the condition of anonymity, elaborated how the permanent faculty could be alienated and ad hoc teachers could lose their jobs if they are seen supporting the queer collective.

“Teachers who support queer students get pushbacks in other ways. Their projects won’t pass through. They will be kept out of certain committees. They might feel as outsiders and won’t feel welcomed or included. They are seen from a particular lens,” said the professor.

Also read: Where are India’s queer parents? Having a family is not even an option for many Indians

Micro-aggression part of college life

The demand for independent queer collectives on campuses has risen from incidents of outright homophobia and the subtle ways in which a heteronormative culture is imposed on queer students.

Men wearing jewellery and make-up or women wearing baggy clothes are pointed out by people on campus.

When a queer student at JMC corrected a faculty that she doesn’t identify as a female, the latter allegedly said, “If you are different, you have to tell me. You are all girls.”

“People are indifferent to a point that they make you feel neglected. This passive aggression made me so mad when I first joined college. I started questioning – why can’t I be myself on this campus?” said Nikhil.

To the students, a wonderful college life is promised by the world where one can live freely as a queer person, says Pooja Nair, consultant therapist, Mariwala Health Initiative, a Mumbai-based queer affirmative organisation for mental health. But when campus diversity isn’t acknowledged and celebrated, students get a rude shock.

“The discrimination may not even be big incidents. There is so much of everyday micro aggression. Someone may not like to sit next to them, or nobody wants to be with a queer person on a group project. People make fun of them behind their back or sometimes to their faces. Queer people may lose friends the minute they come out,” says Nair.

At JMC, an all-girls college, some professors continue to deadname queer students or misgender them despite being corrected multiple times or requested to use gender-neutral terms like students.

When a queer student at JMC tried to explain pronouns in the class, they were labelled as someone who only talks about gender issues all the time.

“I once raised my hand to say something and my teacher snapped, “There is no gender angle here. Keep your hand down”,” said the student, not willing to be identified.

Queer students are often told by fellow students that some jokes can’t be cracked in front of them because they won’t laugh. Or that being a lesbian or a bi-sexual in a girls’ college must be bliss since they are surrounded by girls.

Nair explains that the faculty are immune to queer students’ challenges and don’t even bother attending sensitisation workshops organised in colleges.

“They do not see mental health of queer-trans people as a matter of life and death. They do not understand the gravity of being a queer young student in a college and the kind of struggles they might have to go through. They see it as a fad,” says Nair.

The grievance redressal mechanism in colleges to address homophobia is broken and ill-equipped to deal with it. Such complaints are addressed by the anti-ragging cell and internal complaints committees. But most of the queer students do not take this route because of unresolved past complaints. Or, when abuse happens in virtual spaces like informal WhatsApp and Instagram groups, it falls out of the purview of the college authorities, they claim.

When Priya reported an incident of sexual abuse on campus, the administration allegedly told her that her abuser is suicidal so no action can be taken against her. In Zakir Husain Delhi College, posters put up by the queer collective are often torn and queer students are constantly mocked on their attire, piercings, hair colour and choice of clothes, jewellery or make up.

The abuse in virtual spaces where abusers can hide behind the veil of anonymity is worse, say students.

An Instagram page allegedly started by the Hindu College students called queer persons “brainwashed” and “mentally ill”. In a group of SGGCC students, messages saying “stop this rainbow bullshit” and a photo of a trans person with a caption “what a clown world we are living in” were circulated. Other messages said that queer people are more likely to get HIV-AIDS.

In October, in Zakir Husain College, two Google forms (which are publicly available on the informal queer collective’s Instagram page) to join the queer collective were filled by anonymous people. These were full of homophobic slurs mocking and shaming the collective, says Arnab.

In 2020, in an unofficial college WhatsApp group when Nikhil requested members to not use abusive language, he became their soft target.

“I still remember the horror of opening that group and reading the messages. The number 69 was put in different context, with me tagged in a sexually suggestive manner. I became the butt of jokes in a public group of 256 people. I was not even out with my sexuality at that point. I was having borderline panic attacks. This was when I had just entered college. This was a complete shock,” says Nikhil.

“Nikhil’s complaint went to the women development cell. They said they cannot do anything about it since it’s not a women’s issue,” says Ankit.

Ankit himself was hoping to meet welcoming peers when he joined college. In high school, he would often have mental breakdowns. He would lock himself in his bathroom and cry for hours, tired of the constant bullying in school and neighbourhood. He would change his path and cross dirty, poorly-lit lanes to avoid boys who would tease and harass him.

His home was no comfort to him either. He is not allowed to lock the door of his room or work with his laptop screen sheltered. Last year, a girl from his neighbourhood told his parents that he attended a pride parade. The warning from his father, a policeman in Delhi, was curt.

“We bury ‘such people’ alive,” his father told him, referring to queer persons. His mother told him that she will disown him if he comes out as queer.

He hoped college would be different.

On his first day, he was outed by a friend in a group. When he admitted that he is queer, the boy sitting next to him jumped to his feet and said, “Don’t try hitting on me”.

“The moment I had the courage to accept myself, a guy came and stomped on it,” recalled Ankit.

When Ankit was given the warning from his father, he went into his shell. Nikhil and other queer members of the collective noticed it and helped him come out of his depression.

Ankit and Nikhil then became instrumental in bringing change on campus. As part of the informal collective, they provide strong support to queer students on campus who are still confused about their identity or afraid to openly come out. Queer students have confided in them personally and on their social media accounts.

Colleges are not mandated to have queer collectives. The guidelines of University Grants Commission (UGC) are also silent about these collectives. The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act 2019 lays down how educational institutions must be non-discriminatory for transgender persons. Any act that causes mental, physical, or emotional harm to them shall be punishable with imprisonment and fine. But the students tell ThePrint that they do not have the courage or the resources to fight these long legal battles alone.

“We have no one to go to. The most we can do is call the harassers out on our Instagram stories,” says Ankit.

Also read: Shock and outrage won’t stop Indian parents forcing queer children into ‘conversion therapy’

A platform

In colleges across Delhi University, the numbers in the informal queer collectives are swelling. From a handful at the time of initiation, some of them now have over 100 members. Though the queer collectives can’t end homophobia on campuses, they provide a support system to queer students.

For instance, in April, Miranda House queer collective organised a fundraiser to collect Rs 8,000 for a queer student who was struggling from anxiety, depression, and trauma due to a history of abuse at their household. Previously, a similar fundraiser had collected Rs 14,000 for them, which paid for their 14 therapy sessions. Many more such fundraisers are organised by the college’s queer collective.

In collaboration with Hindu College, Miranda House queer collective also organised a workshop last month on the legal capacity of queer-trans students. The discussion covered the rights, options and facilities available to queer persons in educational institutions.

But while Miranda College queer collective is recognised, others conduct their activities without any institutional support. Recognition, they say, will allow them to book amphitheatres and auditoriums on campus and they won’t have to worry about arranging logistics and other equipment. Recognised societies in colleges also get funds from the management and, in some colleges, students get credits and attendance rebate for participating in collectives.

“A lot of students on campus were very excited and enthusiastic to know that there was a queer collective simply because they felt that there was an organisation that represented their wants and needs and interests. Something they can rely on if they face any issues or any difficulty in regards to their gender identity or their sexuality,” said Mauli Kaushik, senior coordinator, Lady Shri Ram College queer collective, which was officially recognised in February.

The students’ body in LSR conducted a large on-campus survey to assess the need for a queer collective and the response they received was overwhelming. Almost 90 per cent of the students felt that the college needs a queer cell. While 21 per cent students identify themselves as part of the LGBTQIA+ community, more than 52 per cent showed interest in participating with the collective. 68 per cent students believed that they or someone they know would feel more included if the campus has a queer collective.

“Now that we are recognised, we can simply fill a form to get a venue booked, get speakers. We now have a budget approved. Had we not had it, we would have faced serious setbacks,” says Vanshika Gur, senior coordinator, LSR queer collective.

In colleges where queer collectives are recognised, the sensitisation about queer issues has improved, students claim.

Miranda House in north campus was one of the first colleges to have a recognised queer collective in 2018. At orientation and fests, they get to present themselves just like other societies.

But everyday otherising continues nevertheless.

“Sometimes we get looks from people from the administration department when we go there for the collective’s work. There are hush-hush conversations. This makes us uncomfortable,” says Shreya Srikoti, treasurer, Miranda House queer collective.

The credit for colleges slowly moving toward inclusivity goes to queer students on campus, says the south campus professor.

“Five years ago, it was impossible to invite certain kinds of people on the campus, or to hold certain kinds of events. That has changed now. It is all due to the energies the students have spent, their struggles, and the pain that they have gone through,” says the professor.

Once the queer collectives are functioning, talk of deepening the diversity by acknowledging intersectionality has begun too.

“Once I proposed that there should be two presidents and one should be from a marginalised caste. The collective members could not understand why we needed it. But like any other collective, it will take time for the queer collectives to be more refined,” says Osheen Dahiwale, head of study and discussion vertical, Miranda House queer collective.

Also read: ‘No reason to hold them back’ — how courts have become a support system for same-sex couples

A tragic end

On 5 April, Jesus and Mary College lost its pioneer of queer rights—Sam, 20.

Sam was shunned by his family. He lived alone in a room in the north campus, slept only a few hours at night, and did odd jobs to make enough to survive. A week before his tragic end, he could barely push himself out of bed to brush and bathe. His mental health had visibly deteriorated. But, his friends allege, Sam’s professors turned a blind eye to this.

“He had asked for an extension for an assignment. He was in no mental state to write it. But it was not granted to him,” said Sam’s friend from JMC. His unwelcoming family was perhaps the trigger, the friend suspects.

Sam’s death not just scattered the queer community in JMC, it rattled his friends across Delhi University.

“He had no money to eat, but he was the first one to help others. He would foster people’s pets, organise fund raisers for needy students and wanted to establish a south campus queer collective,” said Sam’s friend.

But the community failed Sam. His identity was held invalid by his family, society, and his educational institution.

“The faculty of the department where Sam studied did not step out of their rooms for a week. One teacher broke down in class and asked students how she could help. But were they ever approachable when Sam needed them?” says one of Sam’s friends, angry.

When the students at JMC wanted to organise a memorial for Sam and hold a meeting later, the principal called them and allegedly asked them to only keep the memorial.

On a small pin board, Sam’s friends left notes around his smiling photos. “I am so ashamed of myself. We failed you,” said one note.

Posters in neon colours on the pin-board was another attempt by queer students at the campus at being heard – “Stop misgendering deadnaming”, “All women’s institutions don’t mean we’re all girls” “Gender senitization for faculty and students body”.

But the faculty from the department where Sam was enrolled did not even attend it.

Note: Names of students with an asterisk (*) next to them have been changed on request to protect their identity.

(Edited by Prashant)