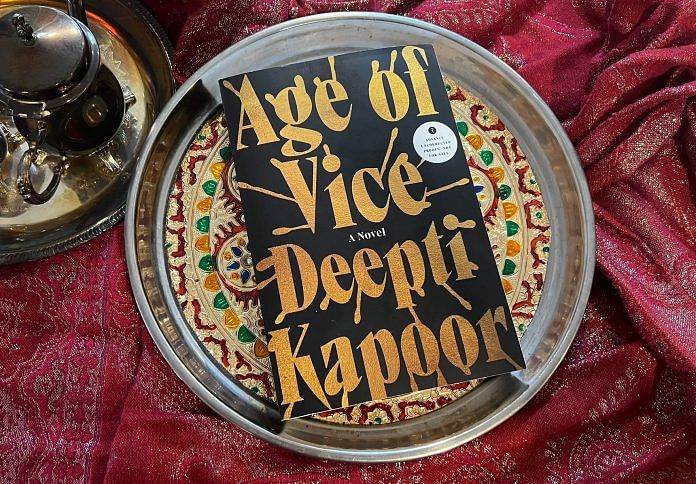

A new novel about class, clout and corruption among Delhi’s Gatsbys is the talk of the town. Anurag Kashyap and Zoya Akhtar want it. The Guardian calls it India’s answer to The Godfather. It has caught the fancy of FX Studio, and its translation rights have been sold to publishers in 20 countries. Deepti Kapoor’s new novel, Age of Vice, is a hit even before its release.

It’s Kapoor’s second novel, and has been in the works since 2019. She’s being hailed as an Indian Marlon James, or Lee Child — both of whom have written blurbs for Age of Vice. It explores power, politics and patronage, in a way that hasn’t been dealt with in Indian fiction in such an engaging manner in a while — not since Vikram Chanda’s Sacred Games (2006), and Megha Majumdar’s A Burning (2020), say publishers.

But it’s not just a novel about Delhi’s Gatsbys. The seed for the story stems from the 2012 Delhi gangrape and its immediate aftermath: Kapoor followed the corruption trail to the nexus of private bus routes that allowed such a crime to take place. “I couldn’t write a book just about rich people,” she says.

Age of Vice straddles the genres of crime thriller and political fiction; it’s a dark, gritty story about climbing the class ladder. Kapoor wanted to explore the imperviousness and impunity of the wealthy in India.

“Our Indian novelists haven’t written good novels about the wealthy,” says publisher Chiki Sarkar, co-founder of Juggernaut Books. “This kind of wealth is bodyguards, high quality vodka, cocaine, Mercedes cars, farmhouses with swimming pools. It’s not about art, propriety, old money, and ‘class.”

Also read: Indians tried new-age Keto, Atkins, Paleo, low-carb. Now they’re going back to Ayurvedic diet

The Western gaze

Kapoor’s 2014 debut novel — A Bad Character — also explores Delhi and its vices though not as brutally, received mixed reviews. But Age of Vice has garnered a lot of international attention, somewhat unusual for a book by a relatively new novelist coming from the global South.

The Washington Post declared it “a rare case of a book bounding as high as its hype.” The novel has “all the energy of a high-concept crime thriller,” made all the more compelling by “the emotional intelligence of Kapoor’s characterisations,” according to The Guardian. Reading the book is “worth staying with these dazzling characters, and this incredible, wild story, to find out” what comes next, says the Chicago Review of Books.

“This is the kind of subject and theme that works for the West,” says Kanishka Gupta, a literary agent. Likening it to Slumdog Millionaire (2008) and its international success, Gupta says her book is more like the Godfather series for India. “She’s a woman writing in a male-dominated genre, and her three-book deal was extremely lucrative in the UK and US — so of course it’s getting some buzz.”

A Burning, too, received this kind of hype, and like Age of Vice, is about the heady intersection of politics and power, and the impact it has on those unlucky enough to have access to neither.

Both Age of Vice and A Burning lift up the covers on India’s story of grit and growth — and offer a glimpse into a developing nation’s dark underbelly.

“Everyone in the West adores Ajay,” says Kapoor — she’s been interested in knowing which of the characters are her reader’s favourites. Ajay, one of the novel’s main characters, stands out against the rest because he comes from a Dalit background and has no privileges. His lot in life is to serve, and the story never lets its reader forget it.

“They say it’s Ajay’s story,” Kapoor continues. “Okay, sure, it is his story — but he’s just a starting point. You move past that into stories of corruption, slums, development.”

Kapoor and her husband, who are both based in Portugal, are involved in developing the novel into a script for an FX show. The pace of the novel would lend itself well to the screen: Kapoor’s visceral writing paints the scenes perfectly.

“What’s excited the West is this adrenaline quality,” says Sarkar. “We’ve seen some of this world in movies and television shows, but not in books.”

Also read: Marx, movies, memories—Saeed Mirza’s book on Kundan Shah, rats and the conspiracy of silence

Where is the great Indian political novel?

While Indian political nonfiction is popular on the charts — with work by writers like Josy Joseph, Sonia Faleiro, Milan Vaishnav, Akshaya Mukul, and Rukmini S doing well — Kapoor’s novel is an interesting addition to Indian fiction. It tells a familiar story about India, one we’re all used to reading in headlines and in essays. But it does so in a literary way.

“You can smuggle in these ideas in a thriller because more people will read them,” she says.

And it works. The best political fiction must succeed as a story first, writes academic Rahul Jayaram, a professor at Vidyashilp University. He lists Vikram Chanda, U.R. Ananthamurthy, Qurratulain Hyder, and several others as examples of this.

“It isn’t politics with a capital P but in the lower case; every ‘politics’ in the farm, mine, factory, household, zenana, agrahara or ashram typifies their best writing. They use their characters to aesthetically examine the milieu they come from. It’s not just politics, but sociology, socio-economics, philosophy and psychology that’s at play,” he writes.

Kapoor agrees with this: her story aims to capture Delhi at the turn of the century, as it transforms from a sedate city into a mega metropolis with the opening up of the economy and liberalisation. She was working as a young reporter in the city at the time, covering stories like the opening of the first metro line or the first bowling alley.

In a way, it’s the perfect novel for someone like Kapoor — who wanted to be a crime reporter but made her way to becoming the first editor of a men’s lifestyle magazine at the publication where she worked — to write.

“What counts as political fiction anyway?” asks Kanishka Gupta. Arundhati Roy’s Ministry of Utmost Happiness and Meena Kandasamy’s The Gypsy Goddess are on his list.

“Frankly I don’t see this novel being received as rapturously in India,” he adds.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)