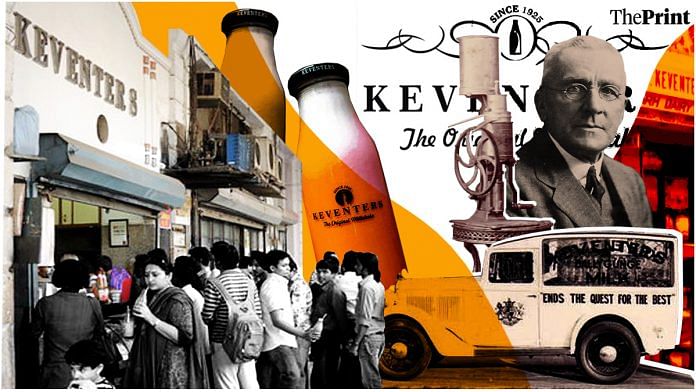

Legacy food brands create a deep comforting presence by linking taste, aroma, and memories. A similar emotional connection was felt when Keventers — a nearly 100-year-old milkshake and ice cream brand — was relaunched in 2014 after a long dormant gap. It was the allure of legacy that persuaded Agastya Dalmia and his co-founders Aman Arora and Sohrab Sitaram to dive deep into history and revive the original flavours, resurrect old packaging bottles, and recreate retro insignias at their outlets. Their decision to use a clip art of the founder Edward Keventer — or Mr K — as their mascot was the ultimate salute to the halo enjoyed by the creator of this sticky brand.

It’s a wise decision considering how dramatic the inception of this brand is. The pictures and the story seem straight out of a Merchant Ivory film. Edward Keventers or Mr K, a young Swedish man, landed in Bombay in 1889 with samples of dairy processing machines — the Alfa Laval cream separator and butter churner. As an independent salesman representing a private machine manufacturer based in faraway Europe, Keventer faced a daunting task. He was neither a cog in the massive British Raj machinery nor a part of the Indian establishment. Marketing and sales persons today would be inspired to read about the effort and sheer zeal of this roving salesman who travelled across India — from Bombay to Madras to Calcutta and also to smaller cities such as Patna, Kanpur, and Aligarh — demonstrating the working of new processes and fanning appetite for these dairy products.

Despite Keventer’s best efforts, the response across these regions was lukewarm since no one was familiar with the concept of dairy processing. Finally, in Bombay, he rented a small shop and began to collaborate with a local Parsi dairy. Soon, the demand for butter increased exponentially in that locality. This perhaps was the advent of the first modern dairy processing setup required to make flavoured milk and butter. These food items, which we now consider most basic and common, were introduced in India for the first time with these modern equipment brought by Edward Keventer.

But before he could build on that success, Keventer’s licence from Bombay’s agricultural division expired, and he was compelled to again scout for opportunities in various towns of North India. After a year of further struggle, he was finally offered a long lease of running a dairy at Aligarh. Thus started the saga of the Keventers brand that Edward and his wife Alma started. Filled with a spirit of adventure and drive, Edward’s nephew Werner came to India at the age of 21 and soon joined Keventer Dairy.

Edward and Werner were the main force behind the Keventer Dairy initiative, and they expanded the Aligarh dairy system prototype to Calcutta, Simla, Ghum, and Delhi. Soon, Keventer’s flavoured milk, butter, and condensed milk became popular across cities.

Dressed often in sarees, Werner’s wife Borguild was a devoted Indophile who provided warm mentorship to local staff and their families. Archival pictures show cows grazing freely in grasslands and clean ventilated stables where bovines were milked by hand. Compared to brutal mechanised dairy systems of today, Keventer Dairy was a compassionate place for animals. The farm labourers too were provided with accommodation and other facilities. In the course of 55 years — from the 1900’s to 1940’s — the original Keventer farm at Aligarh acquired the proportions of a village for 300 people to stay, a school, post office, water supply facilities, printing press, workshops, and even a church.

When tragedy struck

At the end of World War II, tragedy struck the family. The couple was travelling back from Europe via Egypt when Werner died of a sudden heart attack in Alexandria. With their father and chief mentor’s death and India’s imminent Independence, Werner’s wife Bourguild and her four daughters decided to sell the dairy business and exit India.

The Delhi branch of Keventer’s dairy was bought by eminent businessman Ramkrishna Dalmia or RKD. The Dalmia Group was already running a huge number of enterprises, including mills that processed sugar, paper, cotton, jute, cement and engineering plants, insurance, a bank, and even a newspaper — The Times of India — which they sold later on.

Built on a 23-acre plot at the edge of the Malcha Marg area in Delhi — this dairy was perhaps one of the smallest of Dalmia enterprises. Yet it was the one that was most recognised by common people of Delhi. Keventer Dairy’s ghee, butter, cheese, and most importantly, its plump bottles of banana, strawberry, and pineapple milkshakes sold briskly through 48 distribution centres set up by RKD. This is perhaps the time when the Keventers brand imprinted itself on the mind and memories of people. Newspaper taglines saying ‘I scream, you scream, we all scream for ice cream’ advertised their popular cassata slices and carts with psychedelic lights plied residential colony lanes and popular picnic spots such as India Gate lawns. It was one of the first ice cream brands to introduce cones, which became an instant hit.

Even in those days of low-tech operations, Keventer Dairy collected fresh milk from dairy owners in Rajasthan and Haryana and stored it in steel vaults, which maintained minus 4 degrees temperature. Dalmia imported specialised machinery like atomiser to make powdered milk and keedo machines for making condensed milk. These two specialised items were supplied to the Army, and for this reason, Keventer Dairy was given a certificate of ‘Public Utility Service’, which meant they were allowed unrestricted movement and operations even during public holidays.

This seemingly idyllic time got shattered when the Malcha Marg area got declared as a diplomatic zone with almost all the high-security embassies getting located in this part of the city. The 400 or so workers at the dairy seemed like a ‘security risk’ to the authorities who clamped down on them, disconnected their water and electric connection and withdrew their licence to operate. There could not have been a worse time for closure because Ramkrishna Dalmia at this stage was in much turmoil — the split of business operations with Sahu Jain, a messy partition with his brother Jaidayal Dalmia, and a battle of inheritance between his six wives and 17 heirs — leading to an implosion in his various large businesses across East India. In all this shakeup, the survival of the business waif – the Keventer Dairy — was the last of RKD’s priorities.

One thing led to another, and Keventer Dairy, along with its 23-acre plot, was sold to the DLF group of realtors. Miraculously, everything was sold except the name. The brand Keventers itself remained with Gun Nidhi Dalmia — one of Ram Krishan Dalmia’s 17 children.

Also read: From Bahadur Shah Zafar to the Nizam of Hyderabad, a jewellery brand for the royals

Cut to 2014

From the early 1980s to 2014, for almost three decades, the original dairy operations by Dalmia Group remained suspended. Miraculously, the brand remained alive because one of the distributors based in Connaught Place in Delhi continued to sell his own concoction of milkshakes while illegally using Keventers’ branding and packaging. This is perhaps a unique example where the ‘fake’ helped the ‘real’ to survive!

Cut to 2014, millennial inheritor Agasthya Dalmia and co-founders Sohrab Sitaram and Aman Arora decided to resurrect the slumbering legacy. Like Rip Van Winkle — who wakes up to a changed world after a long slumber — it is just the right time for Keventers to revive because food and nostalgia are the flavours of this season, especially if they are served in fat retro glass bottles filled with comforting milkshakes.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)