Delhi: Twenty-year-old Simran Bhat puts on a red bindi, throws her mother’s pink dupatta over her shoulders, and hooks a bronze chain earring onto the upper bridge of her ear. With her father holding the ring light, she hits the record button. And just like that, she becomes Kakyn, a sharp-tongued, nosy Kashmiri Pandit aunt with 40,000 Instagram followers.

But for the apple-cheeked Bhat, this gentle roasting of the older generation is not just a comedy act. It’s a form of cultural assertion. It’s her way of celebrating her Pandit identity and making it relatable for a generation of KPs that’s starting to lose touch with its roots.

“People largely associate Kashmir with Kashmiri Muslims. Not many know what Pandit culture is like. The idea was to give a glimpse into a Kashmiri Pandit household,” said Bhat. Unlike most others her age who were born outside the Valley, she speaks fluent Kashmiri. And she’d like her peers to take a cue from her.

Bhat is part of a growing wave of young Kashmiri Pandits who are attempting to revive their dying culture. Aakriti Chatta films elaborate recipes from her Noida kitchen. Budding filmmaker Anmol Kachroo captures nostalgia in photos and short films, and posts about traditions like Herath (Kashmiri Mahashivratri). Rohit Bhat shares warm videos with his family, including a primer on Kashmiri words—sheen for snow, roodh for rain— and an ode to his mother in the language. Sunandan Handoo specialises in short “Koshur (Kashmiri) humour” videos. His videos often show a father scolding his son, always ending with the same punchline: yemis aava jahnam (may he go to hell).

Together, they’re building a digital memory bank, one Reel at a time.

These young KPs are pushing the migration narrative beyond political injustices and historical trauma. Instead of just grief or grievances, they’re giving a platform to their unique culture, food, language, and history. They remind their followers that they don’t eat wazwan. That they savour Kashmiri lotus stems and collard greens as much as mutton dishes. That married women wear dejhor (a long-chained earring), not mangalsutras. That their festivals, folk songs, and rituals, once performed in the courtyards in Kashmir, now survive within four walls in cities they still hesitate to call home.

Three decades after militancy forced Kashmiri Pandits out of the Valley, the new battle is cultural survival. And these young Kashmiris are fighting for their identity by bringing the memories they have inherited to Instagram.

“The content these young people are creating on social media is not for entertainment. It’s an attempt to keep a culture, that’s facing a threat of erosion, alive. A culture that was left to fade away by apathy. But these young creators are rebelling, clinging to the fading reflections of their heritage,” said author Siddhartha Gigoo, who enjoys watching these videos in his free time.

And sometimes, the videos resonate with an unexpected audience—younger Kashmiri Muslims who’ve never lived alongside Pandits.

“A lot of Kashmiri Muslims message me saying they didn’t know the two communities had so much in common,” said Simran Bhat.

Also Read: Kashmiri Sikhs ask how to stop losing daughters to Islam— ‘It’s a threat to demography’

Channelling mouj and kakyn

To become a 60-year-old Kashmiri Pandit aunt, Bhat parts her hair in the middle to make her face look wider, ties it into a tight bun, and slips into a salwar kameez. It’s a look she’s curated from old photos of mouj (mothers) and kakyn (aunts). Her character’s dramatic laments about love marriages and exam-time scoldings are straight out of any typical Indian household, but with a distinctly Kashmiri Pandit flavour.

Acting, though, wasn’t Bhat’s first calling. It was music. Her mother was a sitar player in Kashmir, and her parents encouraged her to pursue singing. In 2017, she made it to the semi-finals of Gaash Taruk, a Kashmiri Pandit cultural event in Jammu. But it was her spoken words there that left the biggest impression.

“For the semi-finals, we had to introduce ourselves in Kashmiri,” says Bhat.

Watching a 12-year-old raised in Noida speak Kashmiri with flair left the panellists stunned.

“So, they asked me to anchor the shows—and I readily accepted,” added Bhat, whose parents migrated from South Kashmir to the camps in Jammu and later settled in Noida.

It was the way she moved her hands, scrunched her nose, and delivered lines that earned her the nickname Kakyn. The same expressions have made her popular on social media now. In several of her videos, Bhat begins with a cup of kehwa and a piece of Kashmiri bread—a familiar nod to her roots.

Bhat’s fluency in Kashmiri is the product of a concerted effort by her family to preserve their heritage. Kashmiri culture permeates every corner of their Noida home.

Every morning, her mother brews sheer chai (salt tea) in a clay pot. The tea, tinted pink with baking soda, is poured into small, round pyalas—the same kind they drank from in the Valley. A Jammu and Kashmir Bank calendar still hangs on the wall. And despite having a dining table, they still sit on the carpet, lay out a dastarkhan and eat together.

Kashmiri was the first language Bhat learned. “I still struggle with Hindi,” she laughs.

Bhat grew up on stories of resilience passed down from her grandparents. She heard how one dreadful night in the 1990s, her grandfather hurriedly filled two steel containers with rice and dal and made her mother and sister leave South Kashmir overnight in a truck. There was no time to pack anything else. At the Jammu camp, the same rice and dal became their lifeline—it fed them for an entire year. Milk was a rare luxury at that time. But they took Kashmir everywhere.

“They replicated Kashmir in our house in Noida,” said Bhat.

In 2019, Bhat finally decided to share that world online. The idea was simple: seeing a young woman speak fluent Kashmiri might inspire others to learn the language too.

Her early videos didn’t get much traction but instead of giving up, she tweaked the format—speaking in Hindi but sprinkling in Kashmiri words and phrases. Soon, her videos started racking up lakhs of views.

“The language switch was very important. After I made the switch to Hindi, the reach swelled. Now, I get messages from non-Kashmiris who say that they are learning Kashmiri through my videos,” Bhat laughed.

In one clip, Bhat plays the classic neighbourhood aunt—the one with an example for every situation. She speaks mostly in Hindi, slips in Kashmiri, and throws in English translations when needed. In a recent video, her character Kakyn tells a relative that her daughter wants to study in faarin (foreign). She adds, “I told her—when you haven’t even done anything worthwhile in India (nabji taar chate hai), how will you achieve shoob (excellence) in faarin?” The video garnered over 3,000 likes, 92 comments, and nearly 1,000 shares. One comment read, “My mother also says the same.”

But virality came with online heckling. In one of her videos, as she casually mentioned that she was 20 years old. Her followers didn’t believe her and subjected her to mocking comments.

“I realised it was actually a compliment because I had moulded myself into the character so well that my followers couldn’t believe I was so young,” said Bhat, whose bronze dejhor is an ancestral heirloom passed down from her great-great-grandmother.

And now, Bhat has a goal: to make Kashmiri so mainstream that it becomes as widely recognised as Punjabi—a language that people want to learn.

But if Simran Bhat and others—like Rohit Bhat, who has around 38,000 followers—are keeping KP culture alive primarily through language, others are doing it through food, festivals, and nostalgia.

The last storytellers

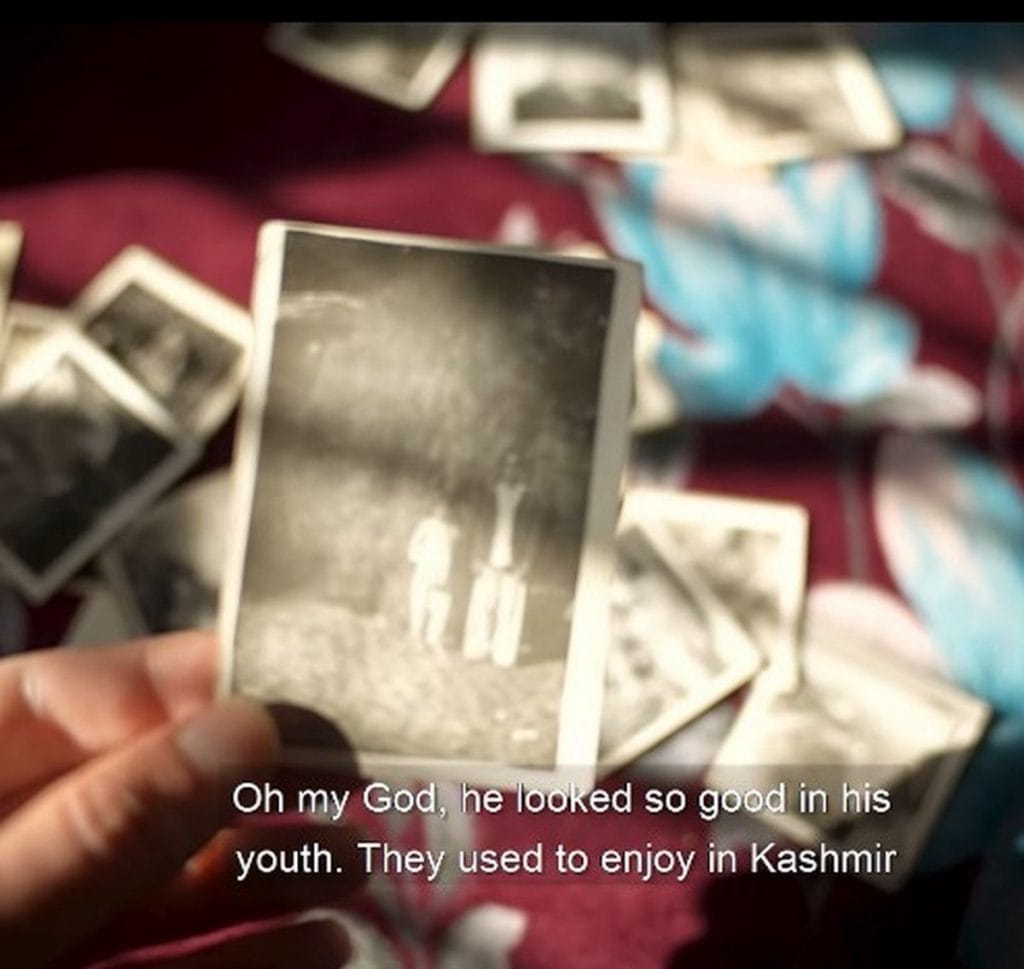

A woman leafs through old black-and-white photos, reminiscing about celebrating Mahashivratri in Kashmir.

“I was cleaning the trunk when I came across these black-and-white photos… See, this is Nishat… and this is Pahalgam. Tathaji had gone on a picnic with his friend. Oh my God, how lovely it is. They used to enjoy so much in Kashmir,” says the voiceover, chuckling nostalgically.

The voice belongs to 26-year-old photographer and filmmaker Anmol Kachroo’s mother. The video, posted on Instagram last week, is his tribute to Herath, the Kashmiri Pandit version of Mahashivratri. It’s part of a series Kachroo started in 2019 to document his community’s life in exile. Another popular video on this theme got nearly 3,000 comments, including from Kashmiri Muslims.

“This valley, our home, has been incomplete without you .Don’t remember those days when you were here, for I was not yet born. Please, come back. This land is as much yours as it is mine,” said one.

When Kachroo started this project, he was studying in Mumbai and surrounded by classmates who knew their cultures inside out. Kachroo realised he couldn’t say the same about his own. The thought gave him sleepless nights.

“I thought that they (my parents) are the last generation who lived in Kashmir. After them, there will be no one left to tell us stories. So, I must document them and preserve this,” said Kachroo.

If Kachroo picked up the camera out of a need to remember, Aakriti Chatta turned to the kitchen.

Also Read: A new breed of fashion influencers is slaying Bollywood star egos and stylist cliques

Haak, hing, and heritage

While working in Pune as a software engineer, 26-year-old Chatta often called her mother whenever she craved home-cooked Kashmiri food. Over the phone, her mother would walk her through the steps.

“After two or three tries, I perfected the art of cooking Kashmiri food,” she said. Soon, she began casually posting reels of her cooking—dum aloo (slow-cooked potatoes) bubbling in a pot, steam rising from a bowl of nadru yakhni (lotus stem in a yoghurt gravy), healthy haak (collard greens).

But it was COVID-19 that turned her into a food blogger. That’s when her DMs started filling up with messages from young Kashmiris living away from their families. They wanted recipes for rogan josh and rajma gogji—the taste of home. She began posting elaborate videos in response, and the appetite for them only grew.

“That’s when I realised that I need to keep doing it. I need to keep the culture alive through cuisine. Social media was to give voice to our food habits and culture, which are underrepresented,” said Chatta, who has over 9,000 followers on her Instagram account khyen_chyen.

Her videos aren’t just about what goes into the pan but what sets Kashmiri Pandit cuisine apart. And soon, her comment section became a battleground for authenticity.

When she posted a tomato brinjal gravy recipe on 3 March, drawing over 1,000 likes, 323 shares, and 67 comments, a man from Kashmir scoffed: “Hing kaun daalta hai?” (Who adds asafoetida in this dish?)

Her response was firm: “Kashmiri Pandits add asafoetida. It is integral to our vegetarian dishes.”

Kashmiri cuisine, she points out, has nuances that are in danger of being forgotten.

“Kashmiri Muslims don’t put asafoetida in their food. They use garlic. We equally eat vegetarian food. And we are equally Kashmiri,” she said.

Kashmiri Pandits, she added, don’t cook wazwan—the elaborate multi-course meat feast associated with Kashmiri Muslim cuisine. There’s no rista or goshtaba. Instead, there’s mastch, an oblong, delicately spiced meatball found only in Pandit kitchens.

Chatta often layers her videos with old Kashmiri songs, posts reels of her husband cooking traditional meals, shares scenes from family rituals, and documents her visits to Kashmir.

During one of those trips, she posted a video with the caption: “Unspoken emotions of a Kashmiri going back to their home as a tourist. Gatch ha Garhe (Longing to go home). Pain.”

For author Siddhartha Gigoo, these digital fragments—recipes, family pictures, Reels of rituals—are more than just content.

“Kashmir will soon be remembered as a place of Kashmiri Muslims because we no longer live there. There will be no signs of us,” he said. “People will remember us through these digital imprints.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)