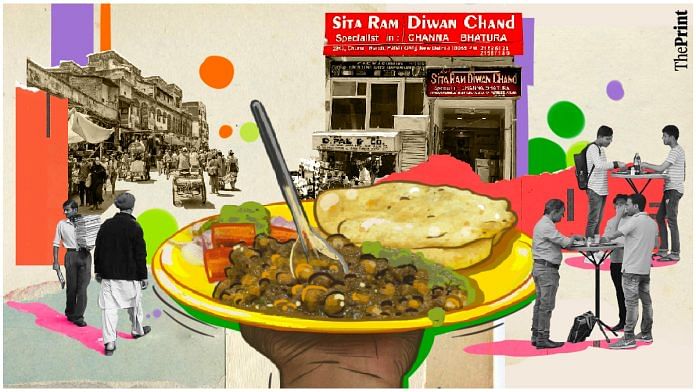

Astute realtors constantly remind entrepreneurs of three key rules of real estate industry — they are location, location and location. Thisis so because location shapes and enhances a business like no other factor. The proof lies in the story of Sita Ram Diwan Chand, which began as a humble chole bhature food cart in Paharganj in 1947. Today, it has a cult following among foodies who throng in large numbers to the restaurant—in a bustling, crowded centre of Delhi—just to relish a plate of this fiery dish.

In many ways, the fortune of Sita Ram Diwan Chand eatery is tied to the story of Paharganj. Like thousands of people who migrated into India after Partition, the founder Sita Ram was barely 15 years of age when he came to Delhi from Lahore. He had no anchor or any means to support himself. Seeing crowds gravitate toward food carts that lined the streets of Old Delhi, he took a cue — and began to look for a spot where he could set up his own food cart. He stepped into the thriving bazaar of Paharganj, which was named after its hilly terrain. At the time, it was a bustling and pulsating place full of traders, transporters, and wholesale merchants of grains from across India. A large number of local residents lived in the upper quarters and ran small kirana shops on the ground floors. Connected to the walled city through Ajmeri Gate, Paharganj was the vital outpost through which goods and people travelled between Chandni Chowk and the Yamuna river.

Building a fortune in a cart

Setting up a small food cart or ‘cycle rehdi’ next to the entrance gate of the local DAV school in Jhula Mandi street of Paharganj, Sitaram decided to recreate a popular Lahori dish—chole with paneer-stuffed bhature with seasonal achaar and chutney. Within weeks, his little stall became so popular that entire families began to queue up. His recipe became such a hit that he decided to shift his small business to Paharganj’s Imperial Cinema.

Sitaram didn’t know at that time that by setting up a couple of wooden planks along the Imperial Cinema wall – he would make his chole bhature venture a part of the refugee ecosystem in Paharganj. A large number of refugees had been granted living quarters and commercial shops by the government close to the cinema. The teeming crowds would visit the Imperial Cinema to enjoy the melodious music and timeless stories of Mehboob Khan, Bimal Roy, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, RK Studio and savour Sitaram’s home-cooked Lahori chole bhature. Over time, this entire nostalgia package became a part of collective memory, and this quaint open-air-one-dish restaurant began to gain traction from far and wide.

Meanwhile, the Paharganj market was undergoing a metamorphosis. Until the New Delhi Railway Station came up near Ajmeri Gate and Paharganj in 1950s, the entire city was served by Old Delhi Railway Station. The new station at Paharganj had a common entry and exit facility for all passengers. Located outside the constraints of the walled city, and yet the epicentre of the new imperial capital, the railway station near Paharganj became a busy hub. Wave upon wave of immigrants were flocking to the capital from across India. Many Paharganj residents found it lucrative to sell off their dwellings to commercial outfits and move out to quieter parts of the city.

Soon grain godowns, kirana shops, and trader hubs too took a back seat. The sabzi mandi and then the grain mandi moved out of this area. In their place, dhabas, juice shops, restaurants, lodges, and hotels emerged. The contours of the market were rapidly transformed by outsiders and all the businesses evolved over time depending on popular demand.

Also read:Halwais to high-end caterers—how Rama Tent House became grand wedding planners in Delhi

Growing and staying same

This transformation further boosted Sita Ram Diwan Chand business and in 1965, Sitaram opened a proper dukaan (outlet) with a live kitchen, a seating area for clients, and a formal area for accounts (or galla as the owner’s seat is called) in Old Delhi. “We have always believed in hard work. My father would wake up early in the morning and open the shop at 7. He would serve the chole on a pattal [leaf plate] to all guests. Alongside, he would make the bill and handle the payments himself. I did the same for 40 years, and now, my son Puneet does the same. There is no break, no holiday. We have to serve 365 days a year,” says Pran Kohli, the owner of Sita Ram Diwan Chand.

The New Delhi Railway Station continued to expand through the latter half of the 20th century. With 16 platforms and 235 trains from across India, the Paharganj market acquired a new and colourful avatar. The proliferation of restaurants and hotels began to don attractive neon lights and eye-catching hoardings, shaping a new skyline. As a result, when the Flower Power movement of the ’70s picked up in India, Paharganj became a popular pit stop for backpackers on the hippie trail. Thus started Paharganj’s rendezvous with nifty coffee shops, rooftop bars with lilting music and a lingering aroma of cannabis.

Despite the changed topography, Sita Ram Diwan Chand always followed one mantra, also the title of a popular film: “Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi”. There has been no change in the age-old methods and proportions in the recipe of the classic single dish served at the restaurant. The khada masala or raw spices are still purchased, cleaned, ground, and blended at the shop. The sour and sweet chutney is still made using dried pomegranate seeds. The achaars offer seasonal bounties with mango in summer, amrak or star fruit in monsoon, amla or gooseberry in winter, and carrot pickle in spring. The bhatura is stuffed with cottage cheese along with aromatic spices like carom and fenugreek seeds along with a sprinkling of asafoetida. The chickpea curry is made with a masala blend containing more than 20 spices.

“Many times, when a grandfather, son, and grandson visit our shop together, we ask them if the taste of our dishes has changed over time. We feel happy when they say – it’s just like old times. The success of our business is nothing but a miracle. Why else would a one-dish restaurant have such a following that people from other cities use mobile apps to order food from us?” says Kohli.

This article is a part of a series called BusinessHistories exploring iconic businesses in India that have endured tough times and changing markets. Read all articles here.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)