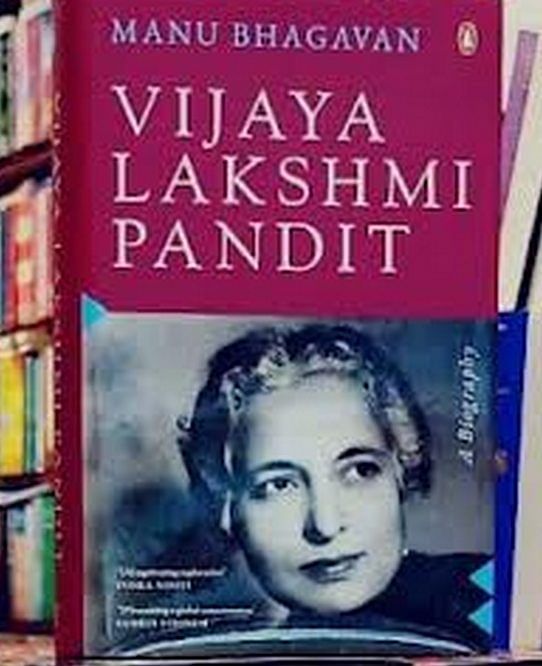

New Delhi: Forget “Jawaharlal Nehru’s sister”. Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit was a force of nature in her own right— a freedom fighter, a minister, and a diplomat who Eleanor Roosevelt once described as “the most remarkable woman” she had ever met. Yet, she has only now received her own definitive biography, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, by author and historian Manu Bhagavan, who traced her life through archives and extensive interviews.

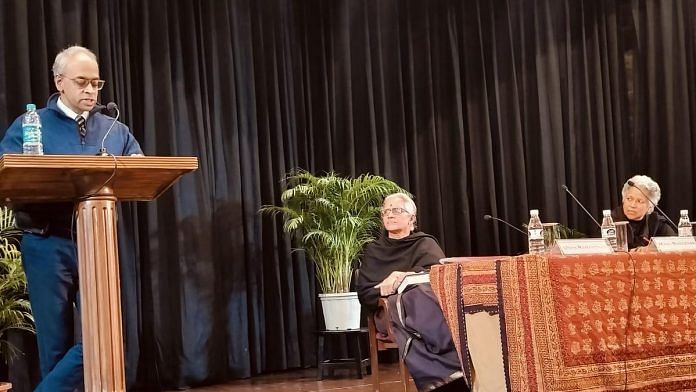

As 2023 wound to a close, the book launch at Delhi’s India International Centre (IIC) saw family members, scholars, and journalists gather to rediscover Madam ‘Nan’ Pandit, as she was fondly called. The overarching theme of the event was Pandit’s largely forgotten legacy, which Bhagavan attributes to two factors: the erasure of her ideas due to her gender and her political rift with her niece Indira Gandhi.

“There’s an active erasure of Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit from history because she went against Indira Gandhi. Her work has almost been scrubbed from public record,” Bhagavan said during his discussion with Gita Sahgal, Pandit’s granddaughter.

Vijaya Lakshmi grew up with her siblings Jawaharlal and Krishna in Anand Bhawan, the ancestral Allahabad home of the Nehru family, but she has been “erased” even from here, he added. “She’s almost a ghost.”

Bhagavan’s biography has been hailed as a groundbreaking work that restores Pandit to her rightful place in Indian history. Nayantara Sahgal, Pandit’s daughter and an author, pointed out in a statement that this is the first attempt to “put it (Vijaya Lakshmi’s life) all together”.

For Bhagavan, a professor at Hunter College in New York, writing the book was a rediscovery of history. “For me, it was the story of 20th-century India,” he said. “I was reading about things that I knew very well about, but as I walked alongside her, the story of history felt very different.”

Also Read: Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, Nehru’s younger sister who slammed Indira for Emergency

Finding Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit

The launch opened with a statement from Nayantara Sahgal, expressing gratitude for “recovering the voice” of her mother. Sahgal, who was initially expected to attend, couldn’t make it due to fog and increasing Covid-19 cases. Instead, her daughter, journalist and activist Gita Sahgal, read out the statement, conveying appreciation for “bringing (Pandit) back into the limelight when she has been forgotten”.

Ironically, Bhagavan’s journey to documenting Pandit’s life began with his own ignorance, he told ThePrint. Several years ago, when he was sitting in his office, an American colleague came into his room and excitedly handed him a project manuscript. “He said his book would be of particular interest to me because of Madam Pandit, Madam Pandit!” said Bhagavan, affecting an American accent.

Although Bhagavan didn’t immediately connect the dots, once he did, he felt embarrassed for not knowing much about Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit.

As president of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) from 1953 to 1954, Pandit was very popular in the United States, earning admiration not only from Eleanor Roosevelt but also charming many on the streets of New York, including taxi drivers.

While working in India on his book The Peacemakers, Bhagavan read more about Pandit at the National Archives in New Delhi. From there, his interest in her grew gradually, and he finally decided to write a biography of her. Fortuitously, he said, Penguin approached him with a proposal for the project just as he was about to begin his research.

Across several continents and 40 different archives, Bhagavan uncovered a wealth of material that was just waiting to be mined. “Pandit’s archives are among the best kept in the country, her work is exhaustive in nature, in the form of letters and speeches. But perhaps her work was not as seriously reviewed as the men of her time,” Bhagavan said.

Also Read: Fear, riots, but no ‘Muslim victimhood’— launch of ‘City on Fire’ puts Aligarh in spotlight

Forgotten feminist

One of Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit’s biggest achievements, in her own view, was her speech calling for freedom from imperialism at the UN General Assembly on 25 October 1945. At the end of his talk, Bhagavan played an audio clip from this historic address, where Pandit also emphasised that “building the future” was an endeavour that “must be shared jointly by men and women”.

Next, Bhagavan provided glimpses into his book by reading out excerpts. One described Pandit’s experience of living in a humble village hut during an election campaign. Her readiness to stay in an impoverished household despite her privileged upbringing provides a contrast between a new India and the old. Back then, Gandhian leaders, unburdened by paparazzi, immersed themselves in the lives of people. Their experiences were not necessarily plastered in newspapers, but their reflections became a part of history.

In a panel discussion, Bhagavan, Sahgal, and scholar Usha Ramanathan also delved into Pandit’s legacy as a policymaker, stateswoman, and representative of India in the US and Russia. Ramanathan lauded the book’s feminist lens, which gives precedence to Pandit’s voice over Bhagavan’s.

Over the writing period, recalled Sahgal, Bhagavan grew so fond of Pandit that he advocated for her even in front of her daughter, Nayantara. When Nayantara pointed out that Pandit spread the ideas of Gandhi and Nehru, Bhagavan apparently politely told her that “she was a woman of her own”.

Bhagavan revealed that Pandit received no formal education beyond school, but continued to seek and acquire knowledge through the rich library at Anand Bhawan. She was thus able to take on the finest minds of her time, often coming out ahead of them.

Yet, dismissive and patronising attitudes prevailed not just during her lifetime, but even posthumously. This was captured in an interview that Bhagavan conducted with an official for the book, in which he sought to understand Pandit’s contributions to India’s foreign policy. “What this official said was that Pandit’s biggest contributions to foreign policy were her fine arms since she wore sleeveless blouses a lot,” Bhagavan recalled.

In the centre rows, scholars and family members listened intently, but half the audience, comprising mostly senior citizens, left before the event concluded. Others had fallen asleep, snoring loudly. Which begs the question — for whom are the ideas of one of India’s finest minds of the 20th century truly being recovered?

The author says he has done his job in finding the voice of Pandit and writing about it. But he leaves it to readers to rediscover her.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)