Pakistan has been debating how to regularise its weapons market, and a state-run company is about to set up an industrial estate around the old ‘gun valley’.

Lahore: Ajab Khan Afridi is an unusual hero. Legend has it that one night in 1923, the Pashtun tribesman and his brother rode towards the lodge of a British officer. Swords and torches in hand, they barged in and killed the officer’s wife. Afridi then picked up the couple’s teenage daughter, Molly, slung her over his shoulder and took her away.

The men, it is said, were furious because the British raided their village and misbehaved with the women. But they never meant to harm young Molly, who was treated well and released by her captors after the British army paid ransom.

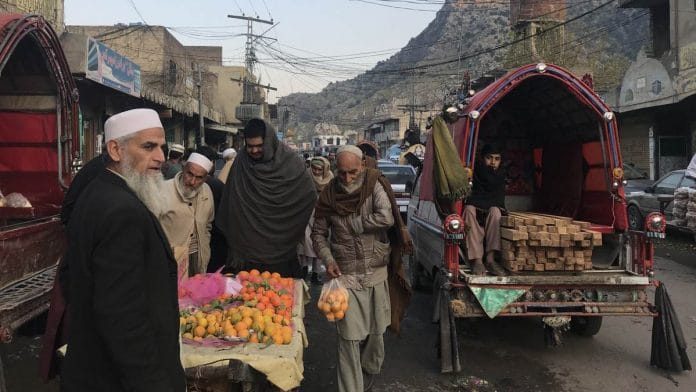

Today, Afridi is an icon in Pakistan’s largest and oldest firearms market — one that is almost 150 years old. His marble statue stands tall in the main square of Darra Adam Khel, a mountainous valley in the northwestern tribal belt, close to the border with Afghanistan.

Pakistan’s ‘Gun Valley’, as it has come to be known, is a small and impoverished town, with a population of an estimated 80,000. Yet, it is home to about 2,000 weapon shops, and according to some, over half the population is employed in making weapons. For most, making firearms is the only thing they know how to do.

Sounds made by hammers, electricity generators and gunshots echo through Darra Adam Khel. The quality of the products is impeccable and nearly impossible to distinguish from the originals. Everything is available here — from automatics and semiautomatics, to 9mm and Beretta, and even anti-aircraft guns — at below-market prices of between Rs 20,000 and Rs 40,000.

Also read: Pakistan’s conventional military deterrence is more robust than commonly assumed

Law-and-order is bad for business

In the 1980s, the valley armed the war in neighbouring Afghanistan, both legally and illegally. Then, in 2008, militants overran the area and a notorious commander took control, though it didn’t curb profits. But when the Pakistan Army launched a military assault in the lawless tribal belt, to scrub it of local and foreign terror outfits, sales tumbled. Pakistan imposed stricter gun-control laws, which further dried up the customer base.

Law-and-order has been bad for business, complain gun-makers.

“The industry has collapsed,” says Gul Zameen Afridi, a 40-year-old who deals in 12-bore shotguns. “Earlier, people would come from all over the world to buy weapons. Now, we are only allowed to manufacture licenced weapons.”

In the old days, a single gun would be passed between six to seven labourers, who would painstakingly chisel each weapon. But now, the thousand-strong workforce is melting away, taking up other professions to earn their living.

Libas Khan, 47, has been in the industry for three decades. He sells shotguns, semi-automatics, 8mms and 7mms.

“I have no formal education,” he says. “Making firearms is the only skill I have learned from my grandfather. None of my eight children go to school, because I don’t earn enough to pay their fees.”

Also read: India cannot satisfy Pakistan enough without reworking the Indus Water Treaty

Plan for a reboot

For a while now, Pakistan has been earnestly debating how to regularise its arms and weapons market. The state-run Pakistan Hunting and Sporting Arms Development Company has proposed setting up an “industrial estate” or a gun town, for which over 200 acres of land near Darra Adam Khel will be acquired. Initially, 500 shops will be set up to control production and the quality of the weapons.

“The government has already begun acquiring land,” says Tahir Khattak, CEO of the company. “Once that is complete, we aim to have this town ready within two years.”

Internationally, the arms trade is big business, which Khattak says the government is finally keen to tap into. Pakistan, at the moment, exports shotguns and small arms to Austria and Lebanon, while its import bill of weapons is close to $20 million from China, the US and Turkey.

“Our exports, as of now, are close to nothing. Only when the imports will be cut off completely can the local industry grow. Already, 10 small arms being produced by Darra Adam Khel are internationally certified. Africa and the UK can be big buyers for these,” Khattak said.

Books, not guns

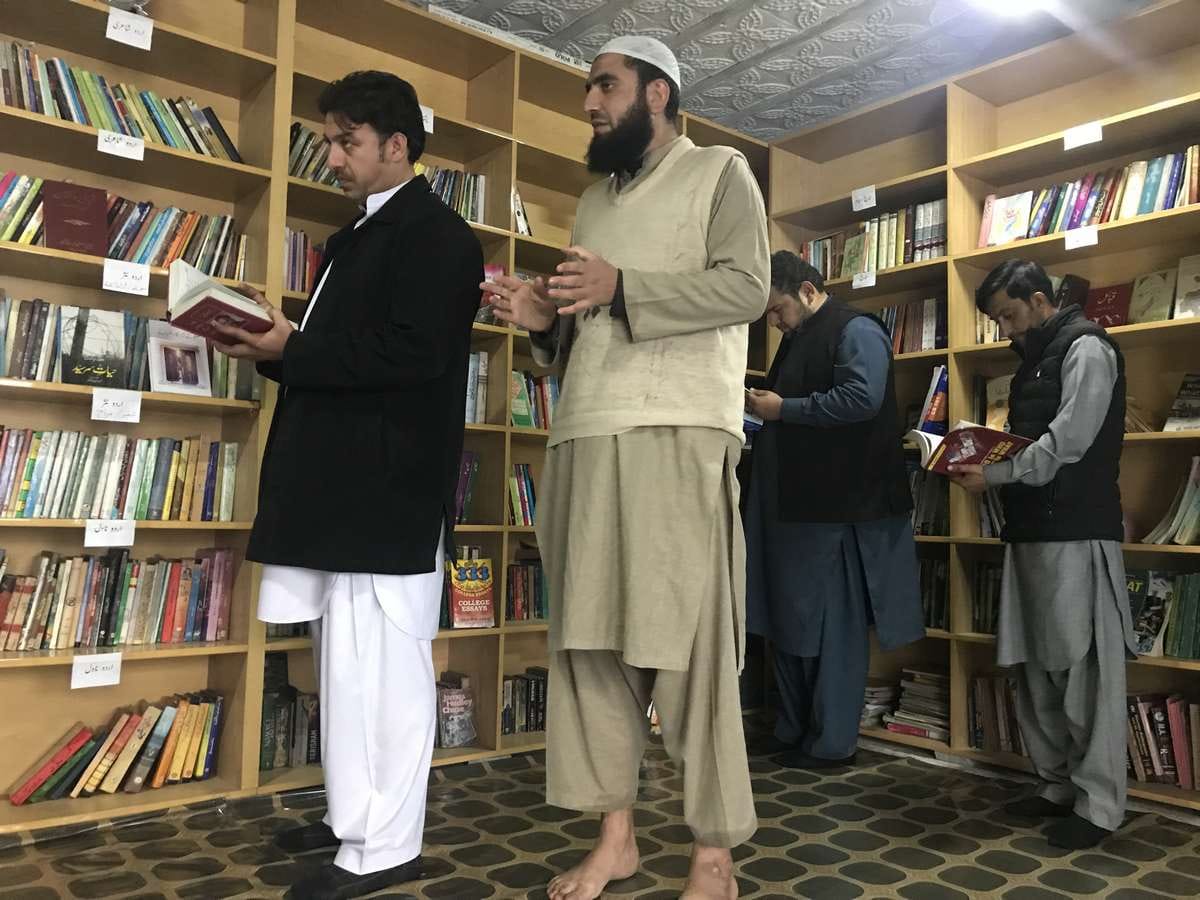

But not all the residents of Darra Adam Khel agree that the age-old tradition of arms dealing and making should continue. Shahnawaz Zeb, 32, is a professor at a private college. His family was also in the firearm trade.

Yet, last year, he went his own way and set up a small library, with donations, in the midst of the weapons market. He then launched its Facebook page, Darra Adam Khel Library, to invite local people.

“I know it is a strange composition — a library on the top floor of a gun shop. But business is not bad,” Zeb says with a chuckle.

His collection includes books in English, Urdu and Pashto. Today, he has 170 members. Most of his regular customers are women, who are not permitted to venture out in Pakistan’s tribal areas.

According to the Bureau of Statistics, the estimated literacy rate among women in the tribal areas is below eight per cent. So, Zeb’s female customers have to send a male relative with a handwritten list of books they would want to buy or borrow.

“Times are changing and we should change too,” says Zeb. “We need to take the guns away from our younger generation and arm then with books instead.”

He then points to a poster behind him that reads “Chheen lo haath se bandooq merei, aur panaah do mujhey kitabon mein (Snatch the gun from my hand and give me shelter in books).”