New Delhi: Many say that Sri Lankan food is an extension of Indian cuisine. This assumption is based on the country’s demography — more than 20 per cent population of the country are Tamilians.

But the similarities don’t travel beyond the Rasam, appam, dosa realm.

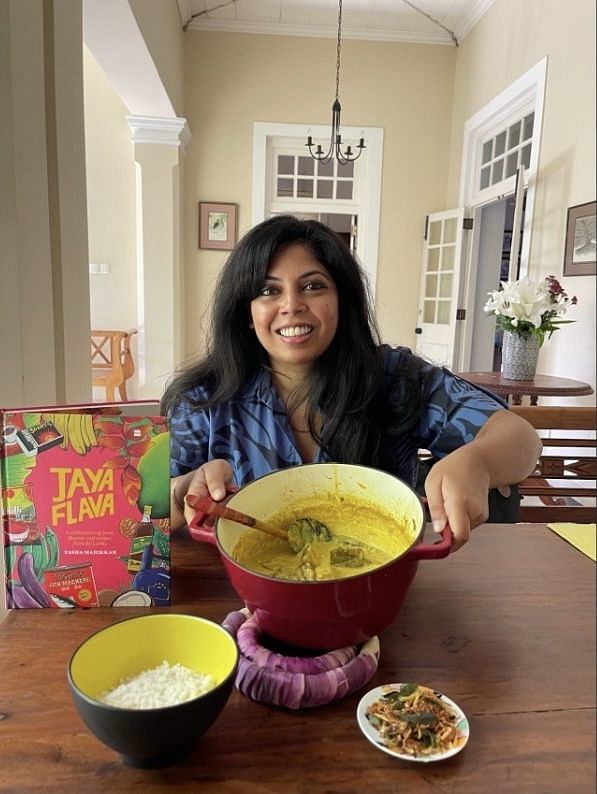

Author Tasha Marikkar captures Sri Lankan food’s individuality in her cookbook, Jayaflava: A Celebration of Food, Flavour, and Recipes from Sri Lanka.

“It’s an attempt to put Sri Lankan food on the world map,” Marikkar told ThePrint. “And, celebrate the many ethnicities in the country.”

After returning to Colombo from London in 2015, Marikkar left her advertising career behind, finding respite in the kitchen. She became the unofficial ambassador of Sri Lankan cuisine. Marikkar has bigger dreams for the country’s cuisine and Jayaflava is a cornerstone of it all.

From mutton poriyal and polos curry to lamb curd curry and chicken curry puffs—the recipes in Jayaflava have multiple cultural origins. They’re a blend of Colombo Chetty, Sinhala, Ceylon Tamil, Indian Tamil, Ceylon Moor, Burgher, Malay and Vedda food cultures.

“Our cuisine is magical and quite hidden from the world. It is far less explored than other South Asian cuisines, I want people to fall in love with it,” Marikkar said.

Also read: Indians have gone too far with fusion food. Gulab jamun tiramisu is perverse

Rainbow cuisine

Marikkar claims to have had “no skills” growing up. She refers to herself as an “indoor child” who spent countless hours in front of the television. Daytime TV was her jam and it’s through it she fell in love with cooking. Marikkar was just six years old when she entered the kitchen.

“Watching Martin Yan [American TV chef] smiling into the camera while using a gigantic cleaver in the early afternoon taught me my cooking fundamentals,” she writes in Jayaflava.

From the age of 11, Marikkar would make Christmas lunches, including a whole turkey, for roughly 20-25 people at her house.

Today, Marikkar does pop-ups of Sri Lankan food across the world—at weddings, private dinners and more. Meanwhile, her family lunches now have a gathering of 40-45 people.

“The love Sri Lankan food, especially curries and seafood, receives is overwhelming. I think it’s also easy to like the cuisine because it’s very dietary friendly, mostly vegan and gluten-free,” she said.

Notably, every season of MasterChef Australia witnesses at least one chef, who has ethnic roots in Sri Lanka.

This year, Darrsh Clarke’s brinjal curry and Savindri Perera’s tropical squid ceviche and lamprais blew the judges away.

While tasting Perera’s lamprais—chicken stock-infused rice, chicken and pork curry, seeni sambol, eggplant, plantain, meatballs, and toasted coconut belacan, all wrapped up in a banana leaf—judges Sofia Levin and Poh Ling Yeow were brought to tears.

“I think this is my favourite thing I’ve eaten in this competition to date,” Levin said.

The liberal use of spices, including the many varieties of chilli peppers, curry powder and their treatment of seafood has given Sri Lankan cuisine an identity of its own. The cuisine is often referred to as a rainbow for its use of colourful and varied ingredients.

Marikkar suggests not getting intimidated by the number of ingredients that go into each recipe.

“Buy the critical spices and curry powders. Once you are confident about the dishes, dial up the heat, make it more aromatic, or keep things mellow,” she wrote in the cookbook, which took four years to publish.

International trade and colonialism have had a huge impact on Sri Lanka’s culinary history. The island nation’s cuisine is influenced by multiple different cultures. For instance, the Indian Tamils who migrated to Sri Lanka in the 1800s. Their version of South Indian food has evolved over centuries in Sri Lanka. South Indian dishes like hopper, string hoppers and mutton poriyal are an integral part of Sri Lankan cuisine.

Other communities, like Arab traders, Javanese soldiers, and the Europeans also left an indelible mark on the Sri Lankan cuisine.

“Without the Portuguese, we would not have chilli in Sri Lanka. Without the Javanese, we would not have lamprais or sambols. Without Arab traders we wouldn’t have beef curry or watalappan and no curry puff without Europeans,” she said.

This melting pot has crafted today’s Sri Lankan identity.

Also read: Delhi food has declined. From Mughals, British to modern era

For the love of cookbooks

Marikkar’s family shares a deep passion for collecting cookbooks, and it’s rare to find a title missing from her father’s bookshelf. In an era where recipe tomes are written by social media stars, they consider cookbooks more than just a collector’s item.

One afternoon, while looking through the bookshelf, Marikkar observed that since 1950 Sri Lankan cookbooks have focused on a single ethnic cuisine.

That’s when she got the idea of uniting the entire island’s food culture in one book. It wasn’t an easy job, but Marikkar took on the challenge.

Her ethnic background—a mix of Colombo Chetty, Sinhalese and Ceylon Moore—lends itself to the task. It’s much like achcharu, a Sri Lankan pickle that is sweet, tangy and spicy.

This marked the beginning of Jayaflava, a team that combines the Sri Lankan phrase jaya wewa and the British slang word flava. Jayawewa is a slogan akin to Jai Hind that means ‘celebration’ or ‘victory’, while ‘flava’, which means flair or style, denotes the freshness and dynamism of Sri Lankan cuisine.

The author travelled across Sri Lanka to capture the rich tapestry of the country’s diverse cuisine for her book. From crab curry and prawn curry to kanji and lamprais, she gathered an array of recipes during her travels.

“If you want to eat an authentic Sri Lankan meal, it’s mostly in people’s homes and Colombo,” she said.

Every recipe was carefully crafted in her own kitchen, where she adapted the methods and spice blends before finalizing the selections for her book.

“I went from a UK size 10 to 14 while curating this book,” she laughed. Out of the 200 Sri Lankan recipes she collected, only 85 made the final cut.

During her culinary adventure, she stumbled upon a variety of curries she had never encountered before, including stingray curry, an oyster dish, catfish head curry, and an omelette made with catfish eggs.

“The omelette was my favourite; I’ve never tasted anything quite like it,” she said.

In her next cookbook, Marikkar promises to showcase her adventures with these lesser-known dishes, which are on the way to becoming extinct.

“Many traditional recipes of Sri Lanka are at risk of disappearing with the older generations,” she said. “But I’m determined to restore them.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)