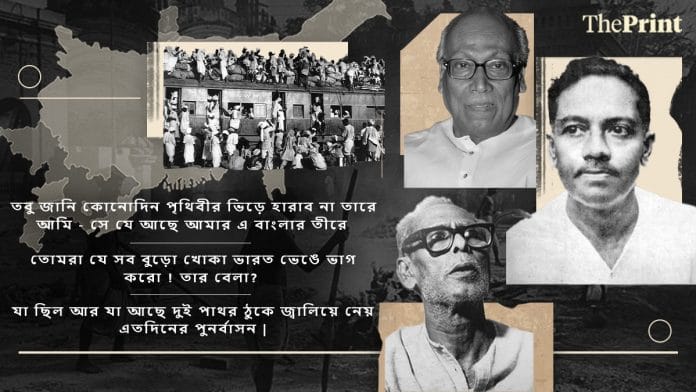

Kolkata: Bengal saw three partitions, but Indian academia developed an acute case of amnesia to it. In all the hype over literature on the Punjab Partition, Bangla’s articulation of loss — especially its poetry — hasn’t got enough national attention.

It has been incorrectly argued that the partition of Bengal wasn’t as bloody as the partition of Punjab — on the contrary, it was equally traumatic, violent, and devastating. The violence in Bengal had precedent in the 1905 partition of the province by former Viceroy George Curzon. The move aimed to suppress the growing nationalist movement in Calcutta, where Bengalis were leading the push for Indian nationalism. On 16 October 1905, when the first partition was implemented, Bengal observed a day of national mourning, Tagore composed Amar Shonar Bangla (which would later go on to become the national song of Bangladesh), and the streets of Calcutta roared with cries of Bande Mataram. What this partition succeeded in doing was mobilise huge masses against the British empire, sparking off the Swadeshi Movement. Within six years, the partition had to be undone.

The second Partition — of Punjab and Bengal — happened in 1947. The allusion of the third partition, is the formation of independent Bangladesh. Language, a key identity of united Bengal, had fueled both the national movement against the British and the Bangladesh Liberation War against Pakistan. The formation of Bangladesh had stemmed out of a disagreement regarding the same language that ‘Bengal’ from both sides of the border shared. So, Bangladesh was a twofold remembrance of the partition pain of Bengal and for a community who for years, had written, spoken, celebrated, and fought for a language that was now spread across borders.

Loss, longing & displaced homelands

Bengal partition literature, especially poetry, which is often a culmination of the memories of all its three partitions, exhibits a recurring theme of longing. There is an astute romanticisation of the past with an even greater yearning to return to it.

A rough translation of an excerpt from Jibanananda Das’ poem Tomra Jekhane Sadh Chole Jao reads somewhat like this:

“All of you, can go wherever you all want to

“I shall remain on this side of Bengal.

I will see the jackfruit leaves, falling, with the breaking breeze of dawn

I will see the earth-tinted wings of herons frosted in evening’s embrace

Their yellow legs, peeking in the darkness, through the soft feathers

Dancing, in rhythm, on the grass

Till suddenly, the Hijol trees of the forest beckon them—

Right beside my heart.”

Das, one of the most powerful poets of modern Bengali literature, was born and brought up in Barisal, which is now a part of Bangladesh. His poems are characterised by imagery of rural Bengali landscapes and wildlife. The ‘Rupashi Banglar Kabi’, or poet of Beautiful Bengal as Das was popularly known, was one of the many who had to migrate to Calcutta after the partition. As the opening line of the poem says, he was also in complete denial.

Nature in Das’ poem is all-encompassing; it has different moods, textures, and emotions. But all the while, it is beautifully soothing. The violence, displacement, and pain of partition for someone rooted in nature would, undoubtedly, be excruciating. He reiterates his initial sentiment toward the closing lines of the poem:

“But still I know, I will never lose her

amidst the world’s chaos—

For she is always on my Bengal’s shore.”

The emphasis on “this side” of Bengal and “my Bengal’s shore” points to two things at once. First, he wants to remain in the landscape he calls home — it lies on the ‘other’ side of the shore. Second, he imagines an undivided Bengal. Das’ Bengal, in essence, is still united by the beauty of its embracing nature. This is the Bengal he wishes to remain in, the home he refuses to lose “amidst the world’s chaos”.

On first reading, Das’ poem appears hopeful; the denial almost a form of ignorant optimism. But a closer reading tells a different story. In a 2022 paper, Md Imran Hossain and Md Saber-e-Montaha write, “His way of depicting pastoral life is unique because he…utilises trees, leaves, deer, grassland, even curlew to transfer human feelings onto them.” In this poem, the dominant emotion in nature is profound sadness expressed through the imagery of falling leaves, cold evenings, and a longing for the dark forest.

These broader feelings of loss, denial, and displacement were common among the entire populace that migrated during the partition.

Also read: Bengali poet Jibanananda Das took over Tagore’s legacy by not trying ‘too hard’

Other articulations

Different poets expressed the sentiment in their own ways, but the difference occurred in the narratives or largely different spheres in which these feelings played out. Faiz Ahmed Faiz writes in his poem Subh-e-Azadi or ‘Dawn of Freedom’:

“This stained, pitted first-light, this day-break, battered by night

This dawn that we all ached for, this is not that one.”

Although the broader theme is denial and loss, the refusal to accept reality is celebrated as the joy of independence. Moreover, the loss is explicit and assertive. It is a nationwide, palpating emotion – much broader compared to the sentiment expressed in Das’ poem. This poem dares to look at one’s face and say: “I refuse your partition.”

In the end, Faiz writes:

“The hour of the heart and spirit’s deliverance has not yet arrived

Let us go on, that goal has not yet arrived.”

Here, he is unapologetically speaking and commanding an entire suffering populace to march on till the goal is achieved.

Das’ tragedy, in contrast, is much more regional and personal, separating his sense of loss from others. He doesn’t speak for the migrant masses.

This retelling of the personal in the context of a partition is also seen in Punarbasan or Rehabilitation by Shankha Ghosh:

“Whatever was around me

Grass and pebbles

Reptiles

Broken temples

Whatever was around me

Exile

Folklores

Lonely sunset

Whatever was around me

Destroyed.”

The poet talks about the exile and destruction around himself – what he has lost and is leaving behind. He uses the partition shock of dismemberment as a literary artifice here. The poem structure is scattered too — the poet is unable to form sentences, so he forces himself to spit out words, sometimes even short phrases to make sense of what is happening around him.

To an extent, it can be argued that the partition hurt Bengal’s historical pride of remaining united against the British. In an EPW article, Dipesh Chakravarty writes: “The past as personal grief: memory that would have expressed itself at the time in numerous acts of personal grieving, in families’ and kin-groups’ sense of loss and bereavement.” Memorialisation, in contrast, “has a public character and seizes upon a historical moment to produce metaphors for public life”. Bengal’s partition poetry is entrenched in memory but often dares to memorialise.

According to Chakravarty’s definition of memorialisation, the poems, by virtue of being read by the public, are acting in the broader sphere of memorialisation of partition. But the intent of Bengal’s partition literature lies loyal to the sphere of memory. It narrates stories of pain, loss, and displacement, all in the realm of very personal grief. Pain sustains itself in the “lonely sunsets”, banks on the ‘self’ often overlooking the ‘other’, and holds personal memories at its crux. This local, regional aspect of a shared and much larger memory feeds into the fact that much of Bengal’s first imaginings of communal brotherhood lay in the idea of a united Bengal rather than a united India. This idea is reflected in both Ghosh and Das’ poems, where the theme of loss is much more grounded in the loss of Bengali land than the larger loss of Indian territory itself.

Even after exploring the uniqueness of various sentiments in Bengal partition literature, the question regarding the amnesia around it prevails. Shelley Feldman, in her essay The Silence of East Bengal in the Story of Partition, argues that the absence was not accidental but a deliberate effort to silence a movement. There is an immediate need, she claims, to re-examine and reconsider the construction of nationalist narratives in India and Pakistan. The oversight regarding the unique experiences of partition in Bengal, particularly the dual colonialism in Bangladesh, would go on to further marginalise certain narratives. There is a necessity to acknowledge the distinctiveness of the Bengali Partition because the implicit subsuming of one collective set of experiences within a larger narrative that primarily focuses on Punjab is itself a hegemonic project.

The myth of the literature vacuum

Many have claimed that not much literature was produced in Bengal during the time compared to Punjab, where Partition literature was a different genre in itself. That has now proved to be a myth — the vault for Bengali Partition literature is equally huge. The problem is the lack of translation, accessibility, visibility, and knowledge.

Moreover, the amnesia does not exist in silos. If we look at the situation in 1947 from a purely administrative perspective, Delhi was the administrative centre for the British. So, when Partition was announced, those who were documenting it naturally reached the capital first. Punjab was much closer to Delhi than Bengal. Partition violence was already rapidly rising in Punjab as opposed to the relatively spread-out communal riots and displacements that were taking place in Bengal in the beginning. BBC archives show ‘famous’ Partition photographs largely taken in the Punjab-Lahore area. The invisibility of the Bengali Partition started right from the primary documentation period.

In this context, it would be interesting to read Ananda Shankar Ray’s nursery rhyme, Teler Shishi (The Jar of Oil), which was composed with the fresh memory of Partition. Monish R Chatterjee writes in a paper: “Rendering a serious subject such as the lasting bruise and trauma of an ethnic and geographic partition…in a children’s nursery rhyme may appear to be the use of a relatively lightweight medium, I would consider it in fact a rather brilliant use of a forum which relatively easily enters into the psyche of a populace”.

“Little Khuku (girl) breaks a jar of oil,

And you’re furious, mad

But look at you grown Khokas (boys); breaking up an entire country

As if that’s not half as bad

Well, what about that?”

A very popular nursery rhyme in West Bengal, it shows that the problem was not with the lack of literature at the time. Bengalis were penning down the ruins of Partition for their children to read and remember. The second and third verses of this rhyme pinpoint what these grown men were destroying. Ray lists the destruction of nations, railways, granaries, mills, shanties, coal mines in a world of no accountability.

Unlike Das and Ghosh’s poems, here, the theme of loss is more direct and asks for answers: “What about that?” The personal element, though, hasn’t quite disappeared; a very powerful first-person voice questions the leaders of the nation. It shows one man’s anger against those who decided to split a united India. There is no underlying hope that the borders will be redrawn.

Also read: Bengal Partition stories aren’t like Punjab. You won’t find violence, but a world was lost

The troubled 1940s

Another reason why Bengali Partition literature remains distinctly different from its counterpart in Punjab, is that writers spoke about death, destruction, and loss as not just an outcome of the territorial split but also starvation and poverty. The 1940s were terrible for the province — just four years before Independence, Bengal was struck with a famine that killed nearly 3 million people. For years, Bengal suffered from poverty, shortage of food and basic amenities and saw death all around.

A lot of the literature produced around 1947 did not place Partition loss at the core. The loss was perceived in the larger context of a hungry, starving, diseased Bengal. This is what Birendra Chattopadhyay wrote:

“There’s an astonishing smell of rice

in the night sky

Someone’s cooking rice even today;

serving it, eating it.

But we stay up the whole night, drowning, in this astonishing smell of rice

We stay up, in prayers, all night.”

The picture of a burning Bengal is depicted in the poem Mrityur Por, Kuri Bochor (After Death, Twenty Years):

“You didn’t have to witness

All the terrible catastrophes

You did not burn in the tortuous fire of ’46

The famine and the epidemic

That came through the blood

When the nation became a nation of sons killing each other,

Fighting for the flesh of their mothers

You did not have to see

The nation’s madness in the Partition of ‘47 which was

Worse than the insanity in Lumbini.”

Here, Chattopadhyay blames those who escaped the hellish conditions in Bengal during Partition. A parallel can be drawn to Faiz’s poem — Chattopadhyay, too, refuses to see this independence as a celebration. For him, it is “worse than the insanity in Lumbini”.

The key difference, however, is that there is no optimism to march on to a better future. There is just an acceptance of reality and terrible anger at the cost of this independence. Many say that Chattopadhyay’s poem was directed at Rabindranath Tagore, who died in 1941. Atabi Saha, points this out and says “however, as Chattopadhyay ruminates, these young poets could not relish the pleasures of dreaming, living in a country which has endured a series of adversities in the years after Tagore’s demise…[the] famous Bengal famine and partition atrocities in the pre-independence period…” He writes in the latter half of the poem:

“But contrary to these experiences

Your life was surrounded by a light of humanity, Poet

We too, had learnt that dream from you”.

Dipesh Chakrabarty in 1995 had written “memory, then, is far more complicated than what historians can recover and it poses ethical challenges to the investigator-historian who approaches the past with one injunction: tell me all” . This is exactly what Bengal’s poets– many of whom found their homes reduced to just memories on the other side of the border– could capture in their verses of loss, displacement, and memory distilling Bengal’s unique partition experience.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)