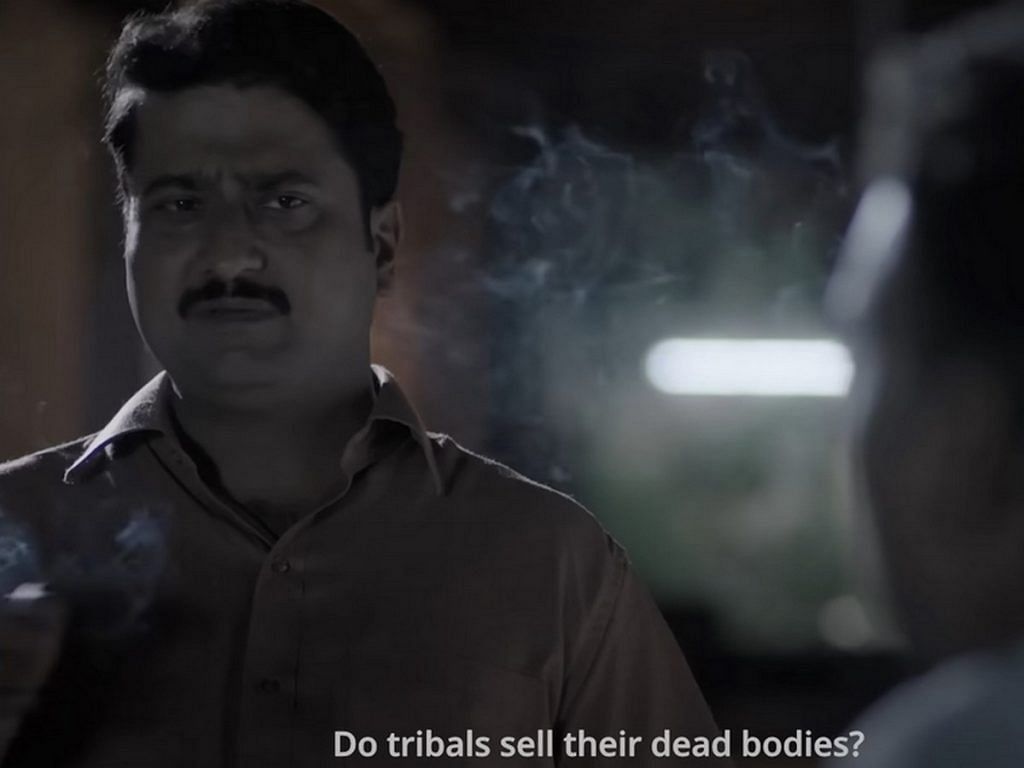

In one biting scene from the Marathi film Ghaath, crooked cop Nagpure tries to cover up his botched attempt to kill a Maoist leader in an encounter. “Do tribals sell their dead bodies?” he asks, hoping to procure a corpse. There are no heroes in this film—just tribals stuck between ruthless Naxals and a self-serving state.

But Ghaath isn’t alone in tackling the Naxal conflict this year. There’s also Bastar: The Naxal Story, which frames the whole issue as a black-and-white showdown: good cops vs evil Naxals.

From Bollywood to regional cinema, Indian filmmakers have long been drawn to the Naxal movement, with its anti-government stance providing fertile ground for storytelling. Directors and writers shift their take on the heroes and villains depending on their political leanings, but the appeal remains the same—forests, firearms, and fierce ideologies make for gripping drama.

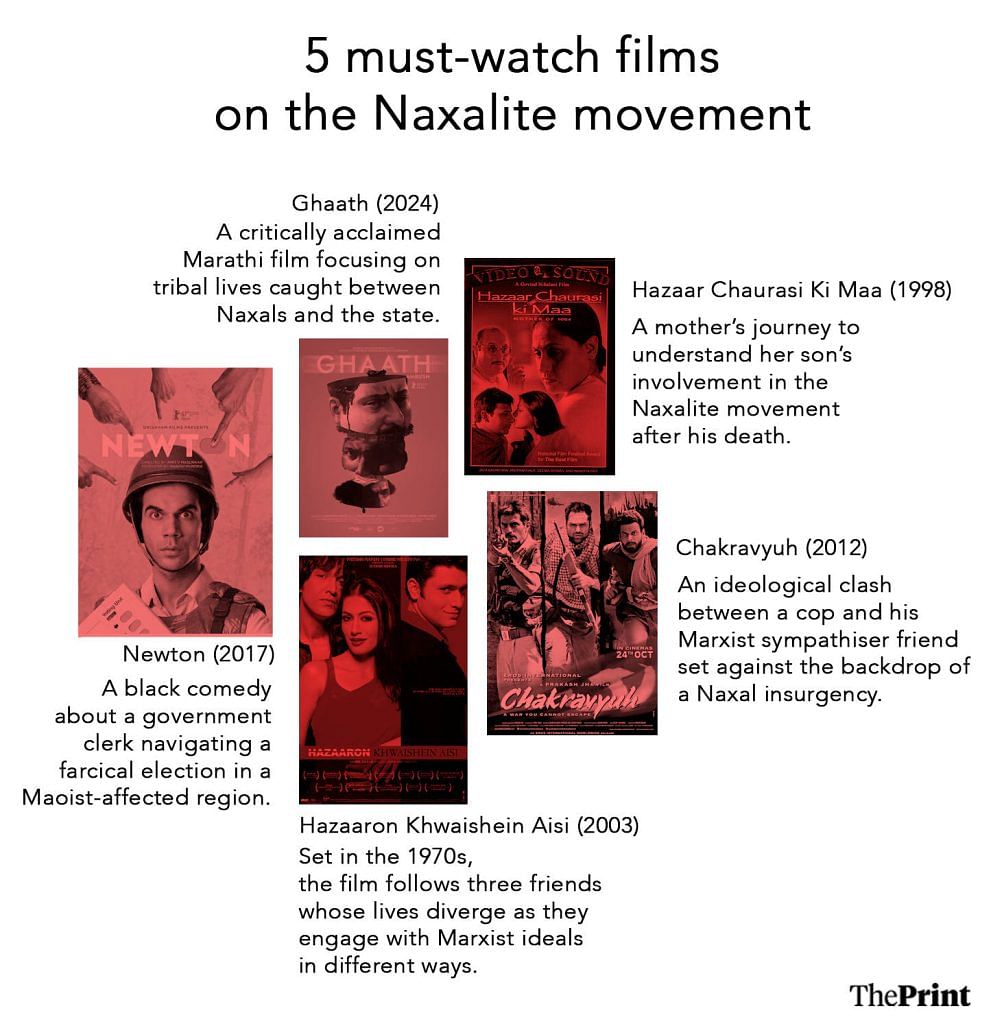

This fascination has spawned a long line of films on Naxalites, from Mrinal Sen’s Mrigayaa (1976) and Shaji N Karun’s Piravi (1989) to Govind Nihalani’s Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Maa (1998), Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi (2003), Chakravyuh (2012), Newton (2017), and Kaushik Sen’s upcoming Hajar Churashir Maa.

“Since the Naxalite movement was anti-state, there was the existing narrative of hunting, running, secret meetings, hideouts, caches of arms, difficulty of fugitive life, and hints of romance. This is probably why the reel has been interested in the movement,” said Sharmila Purkayastha, author and associate professor of English at Miranda House, whose research includes the Naxalite movement.

In the end, everything is about power. Even if the government does have policies for tribals, it is the policeman who will decide because he has the gun. It is the same for Naxalites

-Chhatrapal Ninawe, director of Ghaath

If Ghaath and Bastar offer sharply different takes on the conflict, they’re following a well-worn tradition of Naxal films that explore the movement at various stages. Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Maa zooms in on the dying embers of the movement and the toll on those left behind. Bastar looks at the state’s counterstrike through the Salwa Judum, a vigilante force formed in 2005 and later declared illegal. Ghaath spotlights surrendered rebels, disillusioned cops, and the harsh realities of life on the run.

“What has been consistent with films on the Naxalite movement is that they are set in particular moments of the history of the movement. And the movement itself has evolved, changed, and today it’s on the wane. But what we get to see are certain ‘stages’ depicted on celluloid without a sense of history,” said Purkayastha.

Also Read: Propaganda or political? Bastar: The Naxal Story teaser sparks what Sudipto Sen intended

Guns, government, ground realities

The Maoist-state conflict gets wildly different treatments in Ghaath and Bastar: The Naxal Story.

While Bastar—directed by Sudipto Sen of Kerala Story fame and widely panned— portrays the police as tireless heroes reclaiming the Maoist stronghold of Dantewada, Ghaath shifts its focus to the often-ignored impact on tribals. It explores how land, water, and jungles—central to tribal life—are being torn apart by both the government and the Maoists.

“The meaning of ‘ghaath’ is both wound as well as ambush, and I wanted it to show the nature of the tribal existence in such areas,” said Ghaath director Chhatrapal Ninawe, himself an Adivasi from the Halba community.

At the centre of Ghaath are three characters: Falgun (Dhananjay Mandaokar), a former revolutionary bent on revenge; Raghunath (Milind Shinde), his elusive Maoist leader brother; and Nagpure (Jitendra Joshi), a cop notorious for killing Naxals. It’s a tense cat-and-mouse chase, with Falgun targeting Nagpure, and Nagpure hunting Raghunath to secure a transfer.

The film is divided into three chapters, each titled after the Adivasi slogan “Jal Jangal Zameen” (Water, Forest, Land)—a slogan tribals still use to assert their rights. Through these chapters, Ghaath shows how both the state and the Maoists treat tribals as pawns in a battle for control.

“In the end, everything is about power,” Niwane told ThePrint. “Even if the government does have policies for tribals, it is the policeman who will decide because he has the gun. It is the same for Naxalites—in the end, the man holding the gun decides who is killed.”

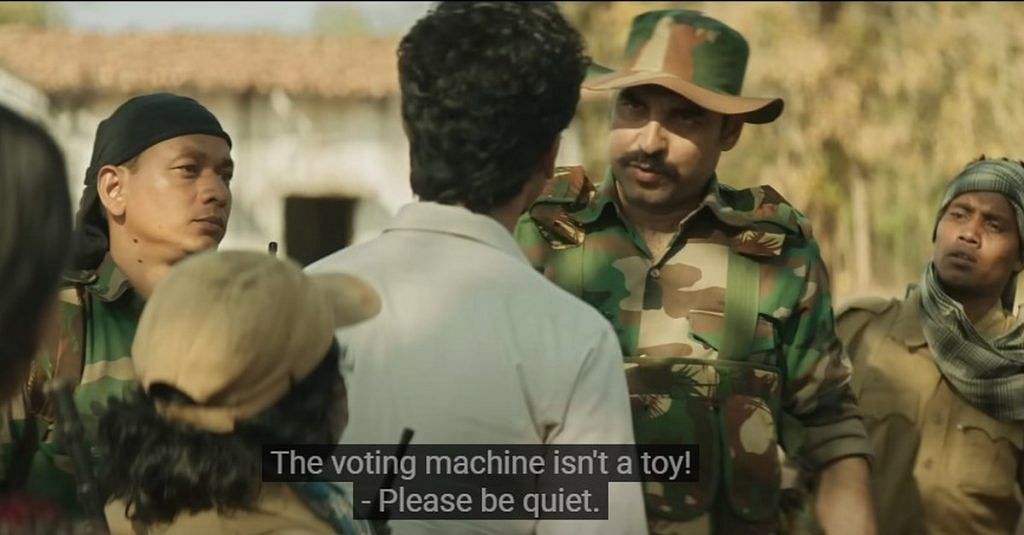

This theme—people caught in the crossfire between the government and the Naxalites—also forms the crux of Newton, a critically acclaimed black comedy directed by Amit Masurkar. Rajkummar Rao stars as Nutan ‘Newton’ Kumar, a government clerk sent to oversee a ‘free and fair’ election in the Maoist-hit Dandakaranya region of Chhattisgarh. What unfolds is a scathing satire on a farcical election that tries to paper over chaos.

“Elections are important for the government to show ‘normalcy’. We wanted to show the people who are sent to establish this ‘normalcy’, like medical practitioners and election officers,” said Mayank Tewari, who co-wrote the screenplay of Newton.

The script was partly inspired by the case of Binayak Sen, a public health professional who was accused of aiding Maoists. He was arrested in 2007 for allegedly carrying letters for jailed Maoist ideologue Narayan Sanyal and was charged with several offences, including sedition.

On a research trip to affected regions, Tewari found governance in shambles.

“What hit us hard is that there is actually no development,” he said. “Local journalists would tell us that they are not able to report fairly because they were targeted as Naxalite informers.”

Newton also asks hard questions about democracy—what happens when people are treated as mere voters, and whether they’re truly represented at all. Indeed, in 2023, as many as 40 villages voted for the very first time in 40 years.

At their core, both Ghaath and Newton examine how the battle over resources has turned both the government and the Naxalites into enemies of the very people they claim to protect. As a character in Newton puts it: “We want to break free from both the government forces and the Maoists.”

Bollywood, Tollywood & city shift

Bollywood’s take on Naxalism has gone from gritty tribal struggles in the jungles to also encompass the ideological sparring of city intellectuals and Marxist sympathisers.

Early films like Mrigayaa (1976) were rooted in rural areas, where state exploitation was the clear antagonist. But this began to change by the late 1990s. Hazar Chaurasi Ki Maa (1998) centred on a Calcutta family discovering their son’s involvement with a Naxal group after his death. The cityward drift continued in Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi (2003), which explored the Marxist ideals and diverging paths of three friends in Delhi’s Hindu College. Then, in 2012, Prakash Jha’s Chakravyuh used the jungle mainly as a backdrop for an ideological clash between a cop and his Marxist sympathiser friend.

Vivek Agnihotri’s Buddha in a Traffic Jam (2016), and the follow-up book Urban Naxals, took a more in-your-face approach, with less nuance. Critics called it outright “propaganda” for its portrayal of Naxalism in Bastar and sympathisers in a Hyderabad B-school. It’s message was far from subtle— beware the intellectuals backing Marxism.

However, regional cinema, especially in states directly affected by the Naxalite movement, has generally offered a more grounded and localised perspective. Telugu cinema, in particular, has produced several films on the Naxalite struggle, especially during the movement’s peak in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Movies like Sindhooram (1997)—not to be confused with the 2023 OTT film of the same name about ‘pseudo-Naxals’—Encounter (1997), Kubusam (2002), and Virodhi (2011) captured the raw realities of the conflict. Kubusam in particular stands out for capturing the convenient posturing of the political parties on the issue, while Virodhi looks at the ideological fissures with the Naxalite movement.

That tradition continues in today’s Telugu cinema, with both serious and commercial films keeping the movement alive on screen, even as it has faded in former hotspots like Warangal.

The mothers of Bastar have suffered the most because of the Naxalite movement. It is not a political film, but an emotional film

-Amarnath Jha, Bastar: A Naxal Story scriptwriter

For instance, Virata Parvam (2022), set in the 1990s, follows Vennela (Sai Pallavi), a young woman drawn into the Naxalite movement in Warangal through her love for a leader called Ravi (Rana Daggubati). The film revolves around their tragic romance but also explores factionalism within the movement, state crackdowns, and the fading ideals of the cause.

As former Naxal Lanka Papi Reddy told The Indian Express: “Even till 2000, revolutionary parties used to recruit intellectuals from colleges in Warangal. These days, corporates pick them up offering hefty salaries. That sums up the state of the Naxal movement.”

Another 2022 film, Acharya, looked at Naxals as protectors of traditional Ayurvedic practices and villages rich in biodiversity. However, both Virata Parvam and Acharya were box office failures.

In contrast, SS Rajamouli’s RRR (2022), the highest-grossing Telugu film of the year, touched on Naxalite-adjacent themes by fictionalising the story of Komaram Bheem, a Gond leader who led an uprising against the Nizam of Hyderabad and local landlords in the early 1900s. While this history of resistance has been the ideological fodder for the Naxalite movement in the region, the film’s portrayal upset members of the Gond community.

“Through this film, we thought (Komaram Bheem) would become known throughout the world. But it looks like they are only using his name. They don’t really seem to be talking about his struggle for Adivasi rights over land, water, and other resources,” said Kanaka Venkateshwar Rao, a teacher from the Raj Gond community.

In RRR, Bheem (NTR Junior) is depicted as a Hindu figure, despite the Gond community following their own spiritual traditions. The film also incorrectly credits Savarna revolutionary Alluri Sitarama Raju (Ram Charan) with coining the slogan “Jal, Jangal, Zameen” (Water, Forest, Land), though it was Bheem who is said to have come up with it.

Ultimately, RRR, like many others, largely relegates tribal and women figures to ‘supporting’ roles. Few movies have challenged that depiction.

Women of the Naxalite movement

Women in films about the Naxalite movement are usually cast as lovers or mothers, serving as foils to the male protagonist— whether he is on the side of law, or against it. Their roles typically revolve around highlighting the ‘normal’ life of both the Naxalites and police. But in a few films, female characters are given more depth, with their own political awakenings.

In Ghaath, a tribal woman, Kusari, is first rescued by the Maoist leader Raghunath from an abusive contractor, only to be raped by him later. Her story is a metaphor for how tribals are exploited by both sides—and shows they must carve out a path without relying on rebels or the state.

“Through her character, I wanted to emphasise how tribals need to shape their own destiny,” said director Chhatrapal Ninawe.

Kusari’s story contrasts with that of Geeta (Chitrangada Singh), in Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi (2003). Geeta starts out as an urban, privileged woman who falls for the revolutionary rhetoric of Siddharth (Kay Kay Menon). While she initially follows the middle-class path of marriage and stability, she later gives it all up to work in a Maoist-affected region of Bihar.

“Geeta is the only character who shows real growth,” director Sudhir Mishra told ThePrint. “She understands that rhetoric is limiting and does actual work— teaching the village’s children.”

Both Kusari and Geeta are lovers, but have an identity beyond the romance. The most politically charged lover, though, is Nandini (Nandita Das) from Hazar Chaurasi Ki Maa. Arrested and tortured by police for information about her Maoist lover Brati, she doesn’t cave and fights back by filing a human rights case.

But it’s often the mother figure that filmmakers use to question the cost of the movement. At the heart of Hazar Chaurasi Ki Maa is a mother’s grief. Set in the 1960s and 70s during the Naxalbari movement in West Bengal, the film, based on Mahasweta Devi’s novel Hajar Churashir Maa, follows Sujata (Jaya Bachchan), a bank worker who only learns of her son Brati’s involvement in the Naxalite movement after his death.

Right after she’s assigned the label “mother of 1084” — the number given to Brati in the morgue — she reflects: “Maut huyi, par khabar nahi ban payi” (He died, but it didn’t make the news).

Forced to confront his ideology, Sujata rejects the trappings of a ‘respectable family’ that had kept her in the dark. Disgusted by her husband’s infidelity and corrupt business practices—both of which Brati opposed—she walks out on her family to honour her son.

A mother’s suffering is also a key strand in Bastar: The Naxal Story, but it takes on a different flavour altogether.

While Nihalini’s film looks at the waning of the movement in Bengal and police brutality, Sen’s film, set between 2010-13, has no sympathy for Maoists. It likens them to groups like Islamic State and Lashkar-e-Taiba. The film drew protests from student groups after a teaser featured a character calling for the deaths of “Leftists” and “liberals,” with some critics also labelling it a “propaganda” film.

“Leftists, liberals, pseudo-intellectuals from cities are behind those in Bastar who are planning to divide India. I’ll shoot these Leftists dead in public. Hang me then,” thunders Neerja (Adah Sharma), a police officer bent on wiping out the Maoists. Neerja is shown fighting while pregnant to underline that being a mother doesn’t soften her resolve.

The film also follows Ratna (Indira Tiwari), a tribal woman whose husband is murdered by a Maoist leader. To make matters worse, her son joins the Maoists. Seeking revenge, Ratna joins the controversial Salwa Judum, a state-backed vigilante militia, and fights alongside Neerja.

Unlike Sujata’s introspective grief, Ratna’s path is one of direct action, with the film portraying her as a warrior. But Bastar has a blind spot—it glorifies the Salwa Judum, ignoring its history of violence and human rights abuses. Ratna becomes symbolic of mothers who’ve lost sons to the movement, yet the film never acknowledges the police brutality inflicted on these same women.

“The mothers of Bastar have suffered the most because of the Naxalite movement. It is not a political film, but an emotional film,” says Amarnath Jha, one of Bastar’s scriptwriters. Describing himself as a former Maoist, he said that the film’s creators travelled extensively across Bastar to gather sources for the movie.

But Prof Sharmila Purkayastha sees the emotional framing in this film as problematic.

“There is somehow this set idea of women as suffering mothers. If they really care about the mothers, they would not make propaganda movies,” she said.

Also Read: Panchayat to Laapataa—villages on OTT are Gandhian simplicity or Ambedkar’s den of ignorance

A widening no-go zone

Making a film about the Naxalite movement, especially one critical of the government, comes with its own set of challenges. Ghaath is a testament to that. One of its original producers, Jio Studios pulled the plug on the film just before it was set to premiere at Berlinale in 2021. The rights were later acquired by Shiladitya Bora’s Platoon One Films, and Ghaath finally premiered at Berlinale in 2023, and got a theatrical release on 27 September 2024.

Newton scriptwriter Tewari also had well-wishers warning him to avoid speaking too openly about Naxalites or the government to avoid becoming a “target”.

As the Naxalite movement fades from mainstream discourse, the few films that address it in a more nuanced way risk being either silenced or co-opted as state propaganda, according to Purkayashtha.

“The Naxalite movement has almost faded away from public memory,” she said. “It’s not surprising that a propaganda film comes just as the government is taking stringent action against a dying movement.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)