New Delhi: Shakeel Anjum Dehlavi sits idle in his 50-year-old bookshop in Old Delhi’s Urdu Bazaar. Many years ago, he had 10 employees serving droves of Urdu readers. Now, only dust stirs on the neglected shelves. The bazaar, once a literary landmark, is now filled with the scent of kebabs and the clamour of diners.

Crowds still fill the narrow lanes of Urdu Bazaar, but they come mostly for Mughlai chicken and mutton biryani, not Mirza Ghalib or Manto. A market that sold lakhs of books each month in its heyday some 40 years ago now has just a handful of fading bookstores, hidden behind outsize signs for biryani joints and travel agencies. As sales plummet and readers vanish, booksellers fret that the legacy of Urdu literature itself hangs by a thread.

“In the past, the lanes of Urdu Bazaar always seemed to be filled with poets, students, researchers, professors, and all kinds of book lovers,” said 65-year-old Dehlavi, the proprietor of Anjum Book Depot. “Now, visitors come to Urdu Bazaar mainly to enjoy biryani, kebabs, and sharbat-e-mohabbat. It’s become just another khana bazaar (food market) of Delhi.”

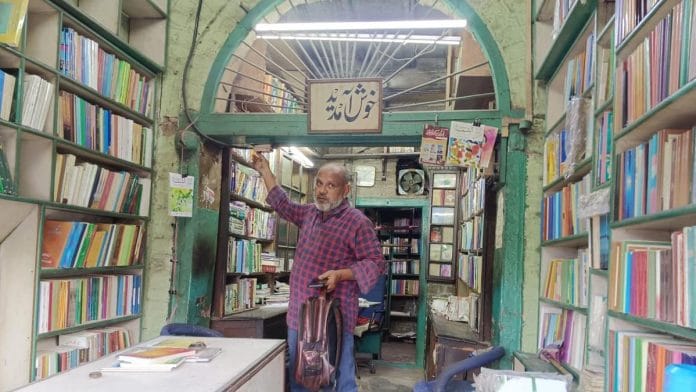

Located in front of Jama Masjid, near entry gate No 1, the market—once famous for its wide range of new, old, and rare books in Urdu, Persian, Hindi, and English—is now struggling to survive. The number of shops has dwindled from nearly 50 to just five.

One of the area’s oldest shops, Kutub Khana Anjuman-e-Taraqqi-e-Urdu, is still operational, but barely, with its shutters down more often than not. A fruit chaat vendor and a kebab seller now occupy the space in front of the store. Many of the most venerable bookstores of Urdu Bazaar are long gone— Lajpat Khan & Sons, Kutubkhana Hameedia, Ilmi Kutubkhana, Kutubkhana Nazeeria, and Kutubkhana Rasheed, to name a few.

“Just as the signboards of bookshops are becoming smaller and older, the number of Urdu readers, both here and across the country, is shrinking,” said Jahidul Rehman, the third-generation owner of Kutub Khana Rahimiya, one of the five surviving bookstores. “If someone were to say that Urdu Bazaar has vanished rather than vanishing, it would not be far from the truth.”

Also Read: Sharif Manzil to Dharampura–how crumbling Old Delhi havelis were restored, revamped, repurposed

An unravelling legacy

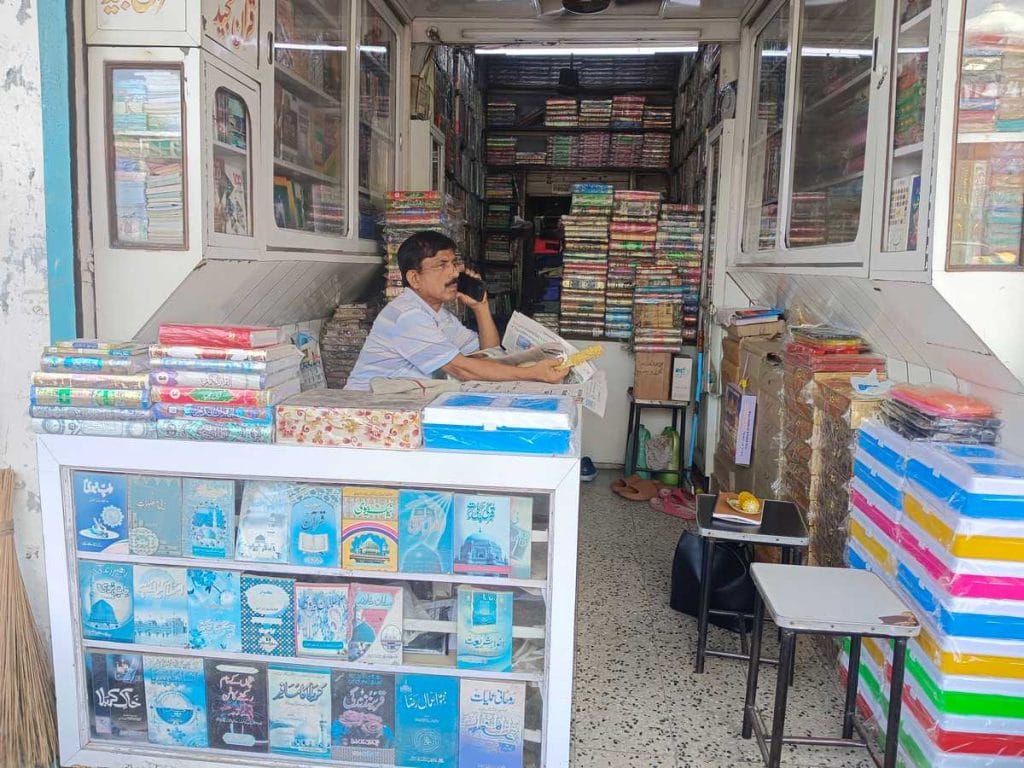

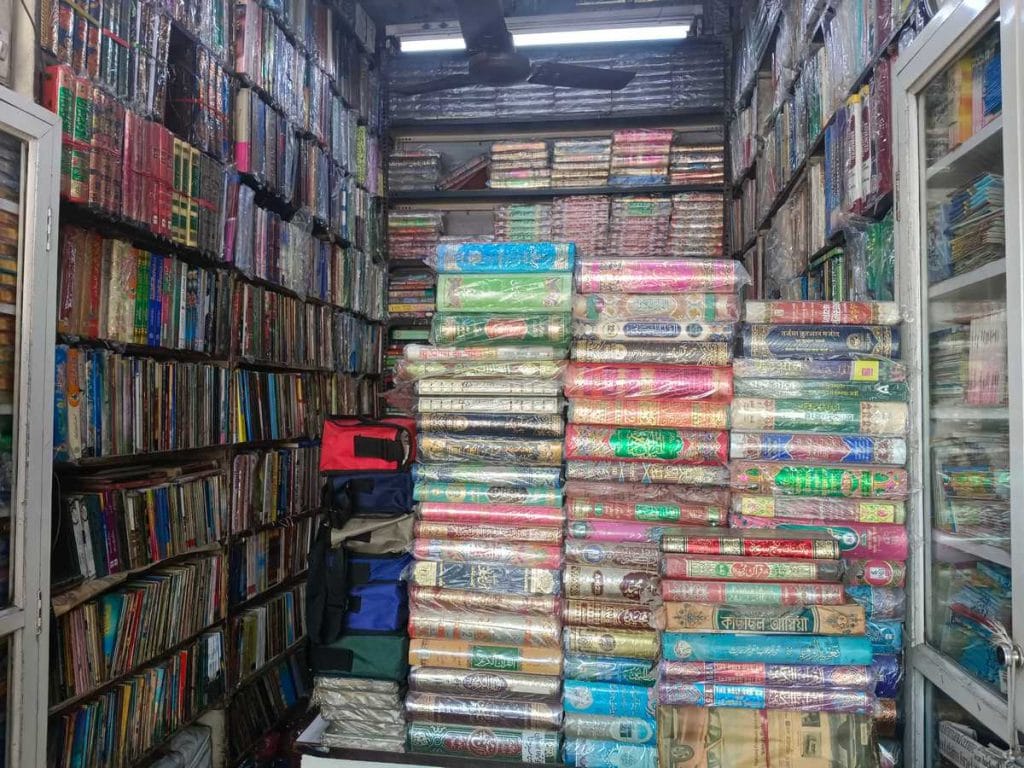

With its graceful archway, framed Urdu calligraphy, and shelves stretching deep into the shadows, Maktaba Jamia Limited still hints at the literary sanctuary it once was. But most of the books have sat untouched for decades, their plastic covers now grey and forlorn. It’s the same story in the other Urdu Bazaar bookstores—Kutub Khana Rahimiya, Anjum Book Depot, Madina Book Depot, and the oft-shuttered Kutub Khana Anjuman-e-Taraqqi-e-Urdu. Most are run by the third generation of their families—a labour of love for legacy, with lower and lower returns.

“Until the 1990s, we used to print and sell more than 50,000, sometimes even a lakh, books each month. Now, it’s down to just 5,000 or even fewer,” said 52-year-old Mohammed Moiuddin of Maktaba Jamia Limited, scrolling through his phone. Due to lack of readership, Maktaba stopped publishing its literary magazines, Qayam-e-Talim and Kitabnuma, in 2019.

For decades, Urdu Bazaar wasn’t just about selling books—it was a hub of Urdu printing, publishing, and poetry.

Also known as Kitab Bazaar or Urdu Mandir, it began with just a few shops in 1920 but quickly grew into a haven for Urdu literature. Poets, scholars, and everyday readers from all over the country came here to read Mirza Ghalib, sip tapri chai, and listen to evening mushairas. Even Jawaharlal Nehru was known to stop by to join the poetry gatherings. In the 1960s and 70s, more than 50 bookstores lined the bazaar, their wooden benches often becoming sites for debates on Urdu versus Hindi.

But the market began losing ground after the 1990s. Reading habits changed, and the once-bustling shops saw fewer customers. The lively debates and poetry sessions gave way to silence.

While the decline of Urdu was already being lamented even in the 1970s— with the New York Times pegging it to “apathy, Hindu chauvinism, and anti-Moslem feeling”— the booksellers of Urdu Bazaar say the biggest tipping point so far has been the internet and digitisation.

“Everything is available in digital format now. As a result, people have also decreased their book purchases. Because of this, we have also reduced our connections with new books and publishers,” said Dehalvi.

But the real loss, for many here, goes beyond business.

Dust to ashes?

The slow disappearance of Urdu Bazaar weighs heavily on its booksellers. For them, it’s also about the erosion of the Urdu language and cultural identity.

Sexagenarian Shakeel Anjum Dehlavi recalled spending his childhood in these narrow lanes, surrounded by the stories of Urdu’s golden days that his father passed down. He speaks fondly about a time when Urdu wasn’t tied to religion, but was simply a language loved for its beauty and expressiveness.

Even though Dehlvi is in politics himself—nominated as Delhi’s Matia Mahal assembly candidate for the AAP in 2013 and then later the BJP in 2015—he blames politics for the perception of Urdu as a religious language. Rehman agrees.

“Earlier, Urdu was learned as a language, and everyone enjoyed reading and writing in it. It was known for its elegance and softness. However, politics not only divided people but also the language itself,” said Rehman.

Many booksellers are now resigned to being the last generation to run these shops. The shrinking number of readers is making it increasingly difficult to sustain the business and support their families.

“Our children have refused to join this family business because of the decreasing customers and low income,” rued 44-year-old Jahidul Rehman. He had once started a career in advertising but returned to the shop full-time because it was more profitable.

But the teenage son of an Urdu Bazaar bookstore’s owner was clear that he did not see much of a future in the family business.

“I want to honour our heritage, but it’s hard to envision dedicating my life to a business that’s struggling due to changing times. Urdu has increasingly become seen as a religious language, and the reality is that very few people are interested in it anymore,” he said.

For many, the only lifeline is religious texts—the last commercially viable corner of the market.

“No matter how times change, people will not stop reading the Quran. Even now, we mostly sell Qurans, and it’s the only reliable source of income for us,” said 34-year-old Mohammad Sherwani, owner of Madina Book Depot.

To stay afloat, the remaining five shops have had to diversify. Along with religious books, they now sell small toys, decorative Quran boxes, and other knick-knacks to attract customers. Some shop owners, though, acknowledge this is just delaying the inevitable.

“We may soon be forced to sell our books to junk dealers and close the shops permanently”, said Dehlavi. “Most of our time is now spent dusting off books and hoping that some of our old customers will call or visit us again.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Good riddance!

Urdu has turned into the language of Islamic radicalism in the Indian subcontinent. Jihadi literature and all kinds of radical and violent ideologies emanating out of various Islamic schools are disseminated amongst the masses through Urdu.