Bengaluru: Aakriti Voruganti, 24, waved her phone near a metro tower at Bengaluru’s bustling KR Market. Around her commuters and shoppers jostled for space, vendors hawked their wares, and buses and cars blared their horns at each other. But Voruganti was transported far from the madding crowd to the 16th century–where the Bangalore Fort once stood in all its glory.

“Bengaluru is usually known for its swanky IT parks and software companies. Many, including me, don’t know that this city was not just born during the internet revolution. A huge part of the city’s rich history left to be unearthed by its own people,” said Voruganti, a senior resident doctor at Victoria Hospital.

The hospital is right across where the fort’s southern gate used to be, but she never knew about it until the words ‘Banni Nodi’ (come, see) on a board caught her attention.

When she scanned the QR code, her phone beeped with images of maps, lithographs, archival photographs, texts, and poetry–all capturing the history and iterations of the Bangalore Fort. Voruganti zoomed in on the colonial maps from the 18th century on her phone, stopping to examine the grainy photos and engravings.

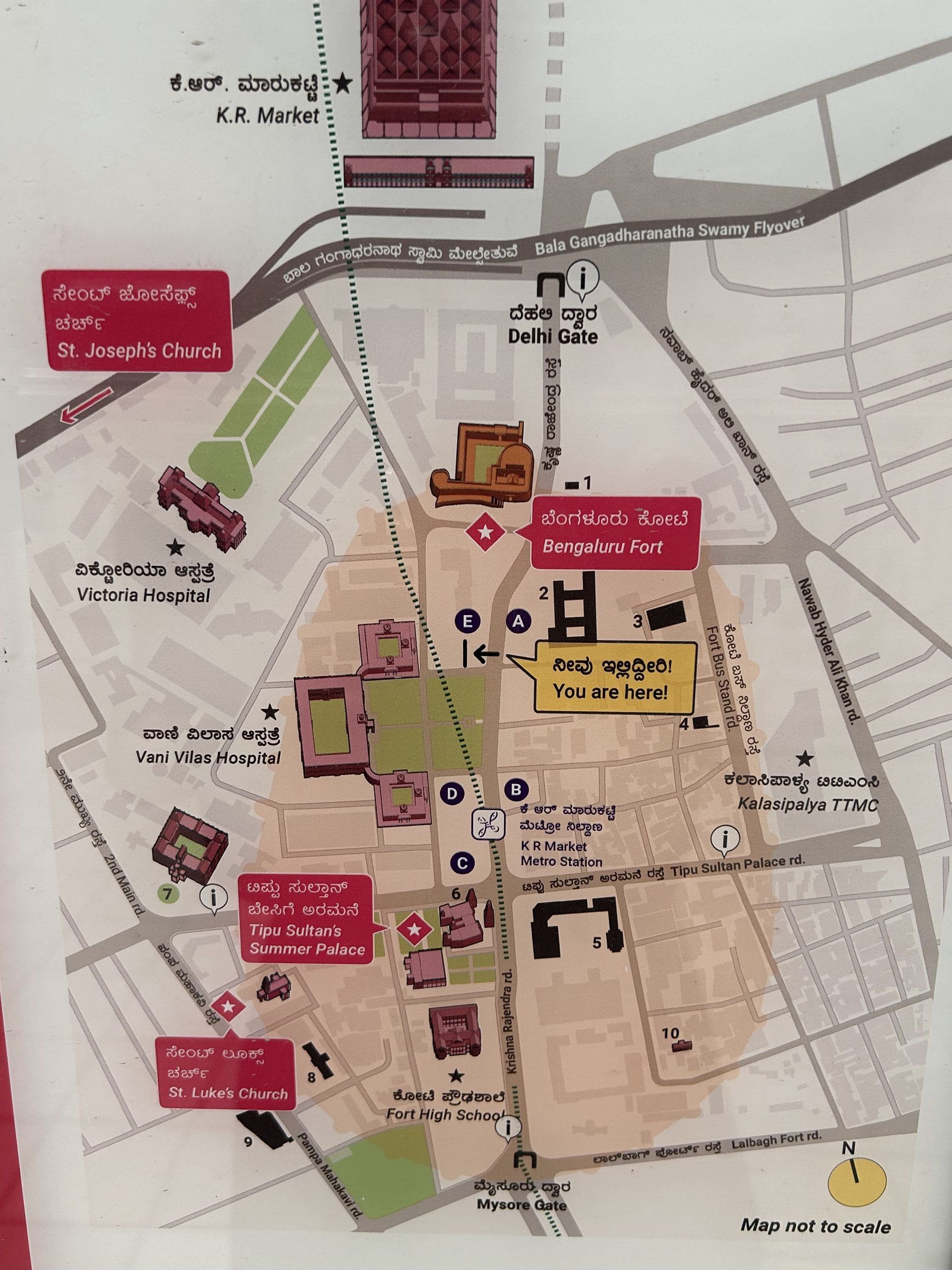

It’s a slice of Bengaluru’s past unfolding, not in the pristine halls of a museum, but in the chaos of KR Market— the Banni Nodi living history project with 15 signboards that has been set up within a 1.5 km radius of Bangalore Fort. Each signage has photos and information in Kannada and English, along with QR codes.

Designed and executed by Sensing Local and Native Place, non-profit organisations working in the areas of urban planning, environment, and heritage, with the support of the Directorate of Urban Land Transport (DULT) and the Bangalore Metro Rail Corporation Limited (BMRCL), the Banni Nodi series is a public wayfinding and placemaking project. But it doesn’t stop with the past. Instead, the information tracks the evolution of the city right up to the 20th century.

DULT officials who played a key role in the project told ThePrint that the goal was to create a site-responsive design that respected the location’s heritage.

KR Market

As he waited for customers, his cart parked just in front of the board, vegetable vendor Ramulu read the information in Kannada. He traced his fingers across the map on the board, trying to figure out where exactly was the battlefield where Tipu Sultan’s army clashed with the East India Company.

“We used to hear stories about the war from our great grandparents who heard it from theirs. But we never knew if they were true. For us, KR Market used to only mean the crowded and noisy market area. But I came across this today,” Ramulu said while enthusiastically pointing toward the signboard.

Vendors sell flowers arranged like curtains in red, orange, and yellow, there are mountains of kumkum (vermilion) arranged on carts, and row upon row of cheap jewellery. A few stop to read the information. By the mid 18th century, it was the stronghold of Mysore ruler Tipu Sultan. This was where the Third Anglo-Mysore War took place in 1790, and the final bloody battle between Tipu’s forces and the army of the East India Company under Lord Cornwallis in 1799.

“A lot of the social fabric of the area has disappeared over the years due to modernisation. Even old historical structures like Bangalore fort and Tipu Sultan’s Summer Palace that used to once exist in the area are now no longer in their original forms,” said Ankit Bhargava, co-founder of Sensing Local, a small interdisciplinary team of urban planners, designers, and architects.

A marble plaque, the Delhi Gate, and four watchtowers are what remain of the Bangalore Fort today—a measly five per cent of what was once a majestic structure.

Ramulu took pictures of the fort to show his two school-going children. He will carry on the tradition of telling stories of the war. But now he knows they’re true. He has old photos on his phone.

Today, the market area is known for its garbage-strewn streets and mucky pavements. Many vendors also lost their space in encroachment drives by the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) in 2019. By June 2017, the KR Metro Station came up. The metro too is symbolic as it is positioned right in the centre of the Bangalore Fort area and cuts through historical structures.

If you take the metro today, you will not be able to see the Bangalore Cantonment railway station, which was once a military cantonment of the British Raj. The more than 125-year-old Victoria Hospital where Voruganti worked tirelessly during the Covid-19 pandemic was inaugurated mainly to help patients during the bubonic plague epidemic that struck the city in 1898.

This change is what the signage project tried to depict, Bhargava said.

“The metro and the area around it both become part of the visual historical experience. This is why we decided to put up the signage both inside and outside the metro station,” he said.

Voruganti now stands in front of a large map, opposite Tipu Sultan’s Summer Palace, a stone’s throw away from KR Market. The map is from the 18th century with details on where the moat and the fort wall used to be. At the time, the palace was far larger than the lone building which survives today. The walls which were once inscribed with floral and geometric work have been now taken over by foul words and graffiti drawn by visitors.

Also read: Korean BBQ is an old fad. There’s a Turkish takeover in Delhi’s food scene

History and language

Like with most history, the debate on what is ‘authentic’ and what is not also found its way into the signage project.

“For a lot of the dates of when historical events happened, the facts were questioned based on sources that were accepted or not,” said Bhargava.

He explained that it was a mammoth process involving translators and historians and spanned approximately eight years beginning in 2016. “There were different people called in for reviewing and authenticating historical content. There was a lack of clarity on who the final sign-off authority would be. It was eventually decided that the Kannada Development Authority would be this authority,” he said.

The creators of the project were also navigating these problems at a time when political parties were appropriating Tipu Sultan’s life and other historical facts of the state for electoral gains.

In the run up to the 2023 Karnataka Assembly elections, the BJP introduced two Vokkaliga characters—Uri Gowda and Nanje Gowda—who, they claimed, killed Tipu Sultan in 1799. The theory was rejected as ‘fake’ by many historians and prominent Vokkaliga seers.

The debate on primacy of regional languages too found its place within the project. Each signage has information in Kannada on top, and English below that. It was a carefully orchestrated plan, according to Bharghava.

“We didn’t want the Kannada information to be merely a loose translation of the English text. We wanted it to convey the meaning and significance of the area’s history in the same way as we intended for an English reader,” he said.

Sensing Local and BBMP were also planning to implement the signage system for 67 other historical landmarks in the city.

“However, after the new Congress government came to power, the Detailed Project Report for this initiative was scrapped. So, the project never took off,” said Hemalatha, Superintendent Engineer, BBMP, who anchored the initiative to expand the project.

Lack of funds was another reason cited by Bhargava. It was expected to cost around Rs 5 crore, he said.

But two months after the project was launched, tourists and even local residents don’t know about it.

“Maybe if it was advertised enough, people would be curious,” said Sarah, 45, a tourist visiting Bengaluru for a couple of weeks from Tilburg, Netherlands, for a photography project.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam khan)