New Delhi: A few years ago, the temple head of a 300-year-old monastery in Lower Assam invited journalist and author Sangeeta Barooah Pisharoty for a visit. He wanted to show her a 15 ft wide and 180 ft long woven drape. It was a replica of the Vrindavani Vastra, a 16th-century Assamese tapestry woven under the supervision of Vaishnavite saint Srimanta Sankardev.

The original silk tapestry was written off as lost until a fragment of it was identified by a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

“Vrindavani Vastra or Brindabani Bastra (as the Assamese pronounce it) is an example of a traditional sacred weave detached from its roots and appropriated into Western culture,” said Pisharoty, who spoke about the art form at the India International Centre on 19 January. Her book, The Assamese: A Portrait of Community, explores the state’s linguistic, cultural and political history, but she chose to focus on Assam’s sacred weaves during the 45-minute-long lecture.

Not only is the Vastra linked to Assam’s oldest cultural traditions, but it’s also led to the formation of the first school of sacred weaves in Assam.

And the re-discovery of the fragment has revived the art form in Assam. The practice of sacred weaves had all but died out in the state though the tapestry itself had an unexpected global footprint—it travelled to Tibet and then Europe. Fragments have been found at the Victoria and Albert, the British Museum in the UK and the Musee Guimet (the Guimet Museum) in Paris. It has become a focal point of cultural reclamation for the Assamese community, said Pisharoty. The replica at the Assamese monastery that she visited is part of this movement.

“Like the rest of India, there also exists a rich tradition of sacred weaves in Assamese communities,” said Pisharoty, adding that it’s often excluded from texts. “While a lot of books talk about the sacred weaves in India, they tend to exclude the Northeast.” Pisharoty says she wants to rectify this.

Also read: This Delhi art exhibit on throwaway culture is full of ‘trash’. The medium is the message

Tibet to England

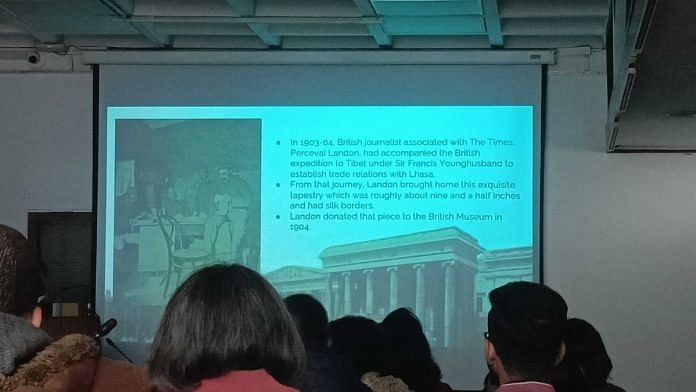

For about 85 years, the rare Vrindavani Vastra remained in the British Museum where it was catalogued as ‘Tibetan Silk Lampas’ because it had last been sourced from that region by a British journalist, Perceval Landon.

He was part of a British expedition to Tibet under Sir Francis Younghusband in 1903-1904 to establish trade with Lhasa. And he discovered nine-and-a-half inches of the tapestry at a Buddhist monastery in Gobshi, which he donated to the British Museum. It was only in 1992 that a senior curator, Rosemary Crill, identified the fabric as the original Vrindavani Vastra during an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In 2017, the Chepstow Museum near the Wales-England border held an exhibition that featured a garment lined with the Vrindavani Vastra fabric.

The tapestry at the Victoria and Albert Museum is decorated with weaves of animals, trees, and stories from Lord Krishna’s life. There are images of the Hindu god dividing the serpent Kaliya and figures of Narasimha, Balarama, and Garuda, as well as Krishna playing the flute in a tree.

Pisharoty made a larger point about how the intermingling of cultures creates practices and rituals— the gods may differ, but the divinity remains intact. It’s how a tapestry of Krisna was found in a Tibetan shrine.

“The ritual importance of textiles in religions transcends civilizations. In Assam, the act of weaving remains a sacred tradition, with rituals like the use of worn cloth for Gosain Kapur or Briha, echoing the sanctity of the craft. The parallel can be drawn to global practices, where prayer mats in mosques and sacred garments in churches attest to the reverence for woven textiles,” Pisharoty said.

However, the revival of the ancient weaves and replicas has divided the community. Is it acceptable to replicate a Bastra woven by a Guru? The devouts don’t think so.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)