Delhi: In 1896, a Viennese gentleman sent the first picture postcard from India to Europe. It showed a ‘nautch’ girl, the goddess Kali holding a demon’s head, ‘Burning Ghat’ and Kalighat. “Greetings from Calcutta,” it said.

The man was W Roessler who operated a photography studio at the time in Chowringhee Road. He’d just realised there was a marketable opportunity with the picture postcard: Europeans must be interested in seeing photographs of their colonial subjects — and he was right, according to postcard collector Ratnesh Mathur. The humble picture-postcards acted as foot soldiers of the colonial expansionist mindset. It reinforced national pride in how much and how far the British Empire had spread and ruled.

Until that point, only words could describe India. But there was significant European interest in seeing what India, fabled as the land of rich maharajas and exotic animals, looked like — and Mathur’s extensive collection of 9,000 postcards shows just how much.

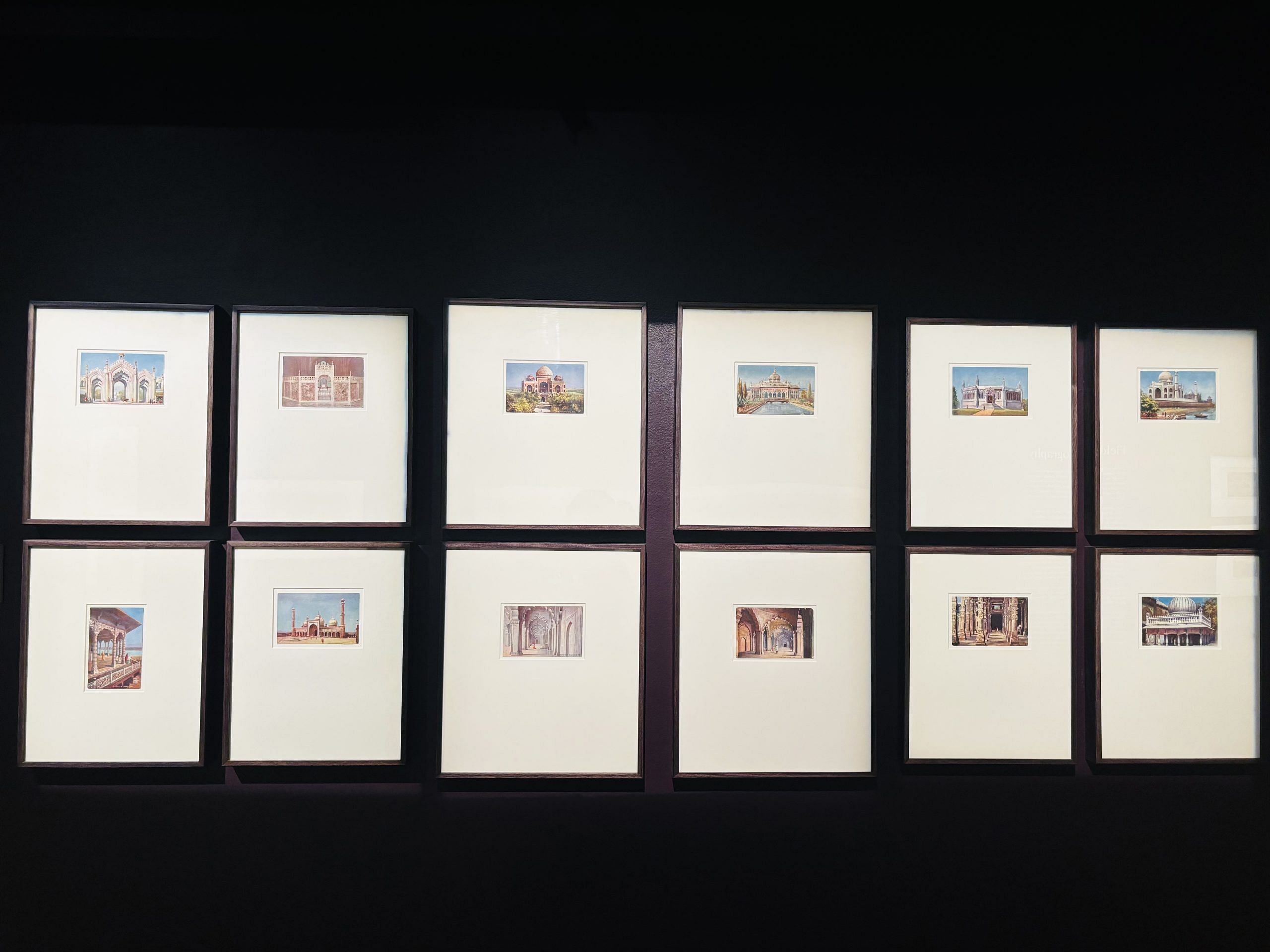

The DAG in Delhi is currently displaying select postcards of India in the early 20th century, which range from paintings of monuments to aerial photographs of cities. On 4 October 2024, Mathur and historian Swapna Liddle held a talk titled ‘Conserving and Disseminating Heritage: The ASI and the Postcard’ as part of the DAG’s exhibition, Histories in the Making: Photographing Indian Monuments, 1855-1920, curated by Sudeshna Guha. It flagged off the last week before the exhibition closes on 12 October.

Liddle opened the talk by illustrating the difference between naksha and tasveer — a piece of draftsmanship versus a portrayal. Postcards and photographs of India at the time were used to document Indian spaces, monuments, and architecture as faithfully as possible — often, details that weren’t recorded in photographs due to lighting conditions or long exposures were supplemented by drawing on the photograph.

“What is the image of India that is being created through this documentation?” she asked, pointing in particular to photographs of crumbling ruins, temples in wilderness, monuments devoid of life. “It’s also a colonial project of recovering the Indian past for Indians, which is really translated into the era of the postcard,” she said.

Mathur then took over the talk, walking the audience of historians, students, and history enthusiasts — who’d gathered late on a Friday evening — through deltiology and his book, Picturesque India: A Journey in Early Picture Postcards (1896-1947).

He flashed another postcard on the screen behind him — the first postcard from the new state of Pakistan. Dated 1 October 1947, it was sent from Lahore to Prague and carried a photograph of the country’s first Prime Minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, bespectacled in suit and tie, and bore the words “Muslim League Zindabad”. On the verso — the reverse side of the postcard — were written the words “Pakistan calling”.

“Pakistan Post was not yet alive, but the postcard was,” said Mathur.

Stereotyping the colonial subject

In colonial India, the kinds of postcards that people were most interested in seeing were racist.

“Who were the intended audience of postcards from India?” Liddle asked Mathur, an ex-banker by profession and a deltiologist by passion.

His answer was mostly Europeans and European visitors to India — whether the postcards were of monuments or maharajas, or statues and elephants, they were of primary interest to outsiders.

“The most popular picture postcards posted from India to Europe are of people — which are making a mockery of Indians,” said Mathur. “Racial stereotypes were the most popular ones sent. Massive events like the Delhi Durbars of 1903 and 1911 were popular too. Then came monuments like the Taj Mahal,” he explained.

Mathur offered only one visual example of postcards with racial stereotypes. A lithograph print from 1902 titled ‘A Fair Exchange’ in which a person buys goods from a seller was exactly translated into a 1910 staged photograph — except this time, it was called ‘Begging for Alms’ and didn’t show a transaction of any goods, but a beggar asking a rich man for money.

He described other postcards, like naked Indian children standing in order of height to indicate a burgeoning and malnutritioned population, and servants working while their masters reclined. People were interested in seeing cantonment life and the lives behind the bungalows.

Of his collection, Mathur estimates that around 11 per cent were pictures of the Bombay Presidency and 9 per cent of Calcutta Presidency. Photos from the Madras Presidency were not as popular. But photos and postcards of working Indians, depictions of caste, hill towns, cantonments, and big events were very much liked.

The 1903 Delhi Durbar, which fell just before the ‘golden age of picture postcard’ — 1905 to 1918, according to Mathur — earned its place in postal depictions. Two English companies, Vivian Manson and Underwood & Underwood, had the contract to print postcards of the event. One of the most popular images was of decorated elephants at the Durbar.

There was also clearly a commercial interest in postcards, which would be sold in bookshops and not just post offices. It wasn’t just the British Raj, even the princely states realised this — the Nizam of Hyderabad, for example, commissioned photographs of Ajanta and Ellora Caves to draw tourists.

Mathur and Liddle also talked about the difference in approach between Indian photography studios and European studios.

HA Mirza, one of the largest studios in Delhi, would publish postcards for which he’d write descriptions in verso “very much as an Indian”. On the contrary, Tucks, the largest publisher of the British Empire, would clearly write for an English audience. The Tucks postcard of the Humayun’s Tomb describes the dome as “¾ the size of St. Paul’s” Church in London.

Gaps in the archive

Some audience members pointed out gaps in the archive, noting that many postcards that Indians sent to each other have been lost to time. Postcards sent to Europe that ended up in private collections can only tell one-half of the story.

“The lack of survival is not the lack of actual existence. Archival loss can’t be conflated with what happened,” said Projit Mukherjee, HoD of Ashoka University’s history department, who attended the talk. He pointed to how things often get thrown out in India, where there’s a much larger recycling culture compared to how European archives would have preserved portrayals of the colonies.

He also brought up the idea of the monument and how it was being captured by picture postcards. “Why should we conflate the idea of the monument with the ASI’s idea of things?” asked Mukherjee. “A lot of Calcutta postcards are of colonial statues — but when we talk of monuments, we don’t talk of those, so we’re buying into the idea of colonial monuments and what was worthy enough to be documented,” he said.

Several of the postcards on display at the DAG’s exhibition were of famous temples and tombs across the colonial empire. The aim was clearly to capture the grandiosity of the crown jewel of colonies. But the usual intimacy of postcards was missing: The messages people were scrawling to each other, presumably complaining about the Indian heat and wishing to escape to colder climes, or poking fun at cantonment life. Similarly, correspondence between Indians themselves — using this new novel form of communication — was missing.

“It would have been interesting for the collector to reflect on the actual senders and receivers — and what they were talking about — rather than the numbers,” said another historian at DAG.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)