New Delhi: It’s the season of pre-something events and celebrations. First, the three-day pre-wedding Ambani gala in Gujarat’s Jamnagar; now, a pre-launch event for William Dalrymple’s new and unreleased book titled, The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed The World.

The book will be out only in September. Dalrymple himself said it is unheard of in the publishing world.

But why wait when the book promises to vehemently prove that India was once truly a Vishwaguru and the font of intellectual, trade and economic activity? All good news about India has to be delivered fast and first.

In a free-wheeling conversation with historian and ThePrint columnist Anirudh Kanisetti in front of a packed audience that held on to every word in hushed silence, Dalrymple challenged three popular understandings of Indian history.

One, the Silk Road isn’t as big of a deal as it is made out to be. The real thing was what Dalrymple called the Golden Road. The latter was a dizzyingly interconnected world of economic and cultural links between India, Egypt and Rome. And India enjoyed unparalleled primacy for a millennium-and-a-half from 250 BC to 1200 CE as a confident exporter on this Golden Road.

Two, the global dominance of Indian trade and ideas came to an end, not because of Turkish invaders like Ghazni and Ghori, but because of the Mongol invaders in 1200 CE.

Three, the Hellenistic-looking Gandhara sculptures of Buddha were influenced by the Romans, not the Greeks.

Dalrymple’s last book, Anarchy (2019), was about the East India Company and was somewhat controversial among nationalists in India. They interpreted it as a free pass for the brutal and extractive colonial empire. But the new book appears to match the current national mood much more. It says that during the Golden Road era, the rest of Asia was the willing recipient of a mass transfer of Indian soft power – exporting merchants, monks, missionaries and astronomers. Like ancient Greece, the book says, India was offering “profound answers to the big questions”.

‘Irritated by the idea of Silk Road’

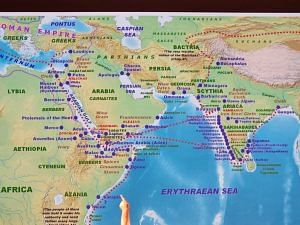

Dalrymple began the pre-launch conversation with something that annoys him to no end – a popular map of what the world now understands to be the Silk Road. It is found in history books, research papers and tourist sites. This map of the East-West contact starts from Jiankang in China, goes through Kashgar and Samarkand in Central Asia and reaches Antioch in modern-day Turkey. This Silk Road map gives India a complete miss.

“I got increasingly irritated with the idea of the Silk Road,” Dalrymple said to Kanisetti, pointing to the map of the Silk Road that places China as the prime mover.

“That is historical nonsense. In the classical period, India was the main organ of the East-West contact. The thesis of my book is that India – not China – was the principal trading partner during most of the late antiquity, and early Middle Ages.”

India was not just the place from which everything went east. It was the main trading partner of the Roman empire.

This Golden Road started from India’s west coast and went all the way up to the Roman Empire – carrying gold, spices, elephant tusks, and cloth. Italian chroniclers bemoaned how rich India was becoming from this trade. Huge concentrations of Roman gold have been found all around the Indian coasts, but these coin hordes haven’t been found in China.

Kanisetti said while India’s trade was funding Roman armies, Roman gold was funding South India’s urbanisation. The earliest cities in southern India came about because of the wealth flowing in from Rome.

According to the calculations on a papyrus stored in Vienna, custom taxes on the Red Sea trade with India, Persia and Ethiopia contributed one-third of the Roman imperial budget.

This created what Dalrymple calls an Indosphere, or an area of Indian dominance. “We need to recover the centrality of India in that period,” he said.

Also read:

When India shifted its focus

When Rome fell, India switched and began looking eastward around the 5th and the 6th century CE. The switch, Dalrymple said, occurred because India had gotten used to the wealth created by the trade with Rome and “needed the gold to keep coming in”.

This shifted the focus of Indian trade from the west coast to the east coast and kicked off the expansion into Southeast Asia. With trade, India’s cultural influences and ideas moved too. Hinduism moved to the Mekong Delta and Buddhism to China respectively.

“The largest Hindu temple in the world is not in India, it is in Cambodia,” Dalrymple said. “Buddhism went from here to Afghanistan to China. And it’s an extraordinary fact that an Indian religion dreamt up in the Gangetic plains takes over China. By the 7th century, briefly, Buddhism becomes the state religion of China. It was an Indian takeover. A whole cast of characters – not just politicians, but astronomers and mathematicians – take over the court in China.”

Dalrymple called it the “radiating waves of Indian influences”.

Also read:

How the Silk Road took off

The phrase ‘Silk Road’ itself was coined by a German geographer in the 1870s and didn’t enter the English language until the 1930s.

The Silk Road was indeed important but not until the Mongol period. That put the break on the peaking Indian influence.

Dalrymple joked that the anger against Turkish invaders may be burning Indian WhatsApp groups these days, but it was the Mongol invasion that truly altered India’s destiny. That is when the Silk Road took off; India was cut off from the old trade routes, and new ones were formed connecting China to the Mediterranean.

Also read:

Who influenced Gandharan sculptures?

The other truism that William Dalrymple dispelled was that the Gandhara sculptures of Buddha – characterised by a muscular body, fine drapery, a head full of curls and a top knot – were influenced by the Greeks. This is something that has been taught in art history classrooms across the world. Dalrymple, however, attributed this influence to the Romans. According to him, 19th-century British historians romanticised and misinterpreted it as the enduring Greek influence of Alexander’s surviving soldiers after his death.

“It is actually not Greek but much later Roman art that is coming from an astonishingly busy and rich trade with Rome from four centuries after Alexander died,” he said.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)