Filmmakers in India have long turned to popular folk and historical figures to depict nationalism and secular ideals on the big screen. However, after 2014, ‘historical’ movies became a means to propagate not just anti-Muslim sentiments but also Hindu majoritarian ideology, warned film scholar and former Jawaharlal Nehru University professor Ira Bhaskar at a recent event in Delhi.

Bhaskar was delivering a lecture titled ‘Nationalism and Popular Cinema: Emotive Commitments, Transformations, Critiques and Alternative Imaginings’ to a packed hall of authors, academics and filmmakers at India International Centre. Part of the 20th edition of The IIC Experience: A Festival of the Arts, it unpacked the legacy of nationalism within Hindi cinema.

Even Jawaharlal Nehru was aware of cinema’s power to spread unity, Bhaskar said, citing the example of Yash Chopra’s 1961 film Dharmputra. Chopra’s second directorial venture after Dhool Ka Phool (1959), it critiqued Hindu fundamentalism and communalism during the Partition.

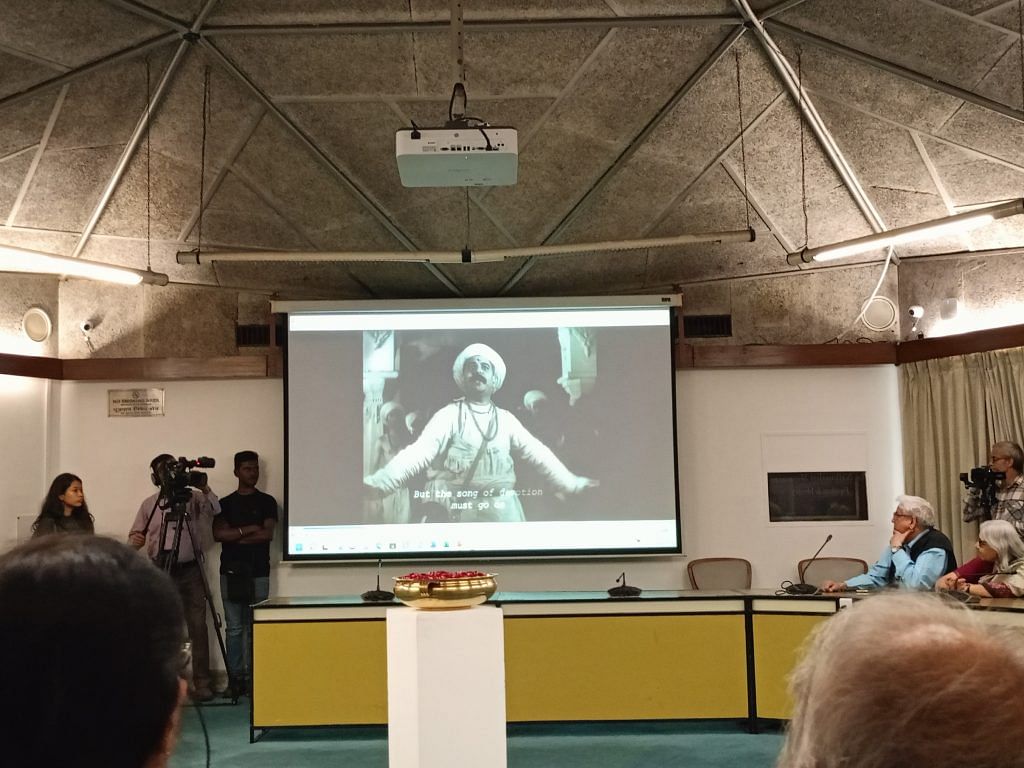

Dharmputra tells the story of a Muslim boy raised by a Hindu family who grows up to become the leader of a Hindu group forcing Muslim families out of India. The character (played by Shashi Kapoor) is even willing to resort to arson and killing to achieve this objective. However, the movie concludes with a tearful reunion of his birth and adoptive families, making him realise the importance of secularism as a video of Nehru’s ‘Tryst with Destiny’ plays in the background.

“Nehru was shown the film and he was so impressed by it that he declared it should be screened in schools and colleges,” said Bhaskar after screening the Dharmputra clip featuring the prime minister’s historic speech.

Throughout her hour-long lecture, Bhaskar liberally used slides, archival images and videos to explain how Indian nationalism has evolved through the years.

New-age Muslim social dramas

According to Ira Bhaskar, cinematic critiques of Hindu majoritarian nationalism are mostly limited to less commercial, or independent, film ventures. Movies such as Dharm (2007), Shahid (2013), Mulk (2018) and Nakkash (2019) are examples, she said.

“Three of these films have been set in Benaras, and the city seems to be the locus for the struggle of the soul in India, as in, the earlier idea of a plural multi-cultural society can be seen to be rent in shreds before our eyes,” said Bhaskar.

Mulk is probably the only one among the lot that qualifies as more ‘mainstream’ thanks to Rishi Kapoor and Taapsee Pannu, Bhaskar added. It is also important because it starts as a portrayal of Muslim life before evolving into a courtroom battle. Films like Mulk are part of ‘Muslim social dramas’, a category that was once extremely popular and commercially successful in Bollywood.

“The very idea of the nation at the time of Independence is powerfully upheld [in Muslim social dramas] as the laws of the land, along with faith in the justice system and the Constitution of India,” she explained.

Such films follow in the footsteps of ‘parallel cinema’, which challenged notions around caste, class and religion in the 1970s and 1980s, she added. Ankur (1974), Nishant (1975) and Aakrosh (1980) questioned caste and class biases, while Garm Hava (1974), Dastak (1970) Tamas (1988), and Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro (1989) focused on the themes of Muslim plight and communalism. Meanwhile, though popular commercial cinema stayed away from touching such topics, it did depict the ‘angry young man’ who was unhappy with systemic problems and corruption.

Bhaskar mentioned two reasons why Coolie (1983) stood out among its ilk. “Amitabh Bachchan plays Iqbal Aslam Khan [in Coolie], bringing in both class and religion.” By casting Hindi cinema’s biggest star as a Muslim working-class hero, the film brought both Muslim and blue-collar issues to the mainstream, she added. Before this, Muslim characters played second fiddle to the protagonist, typecast as “good Muslims” like Khan Chacha in Sholay (1975) and Sher Khan in Zanjeer (1973).

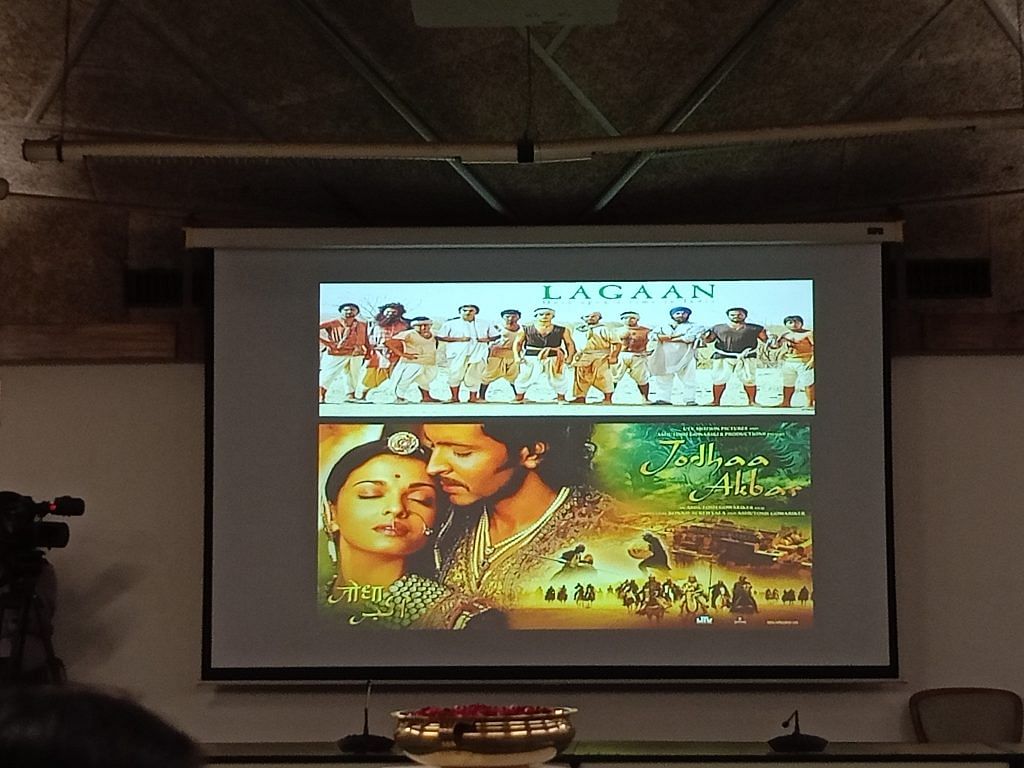

Such depictions, Bhaskar said, changed with the demolition of the Babri Masjid and the advent of the Ramjanmabhoomi movement in 1992. However, films like Bombay (1995), Hey Ram (2000) Lagaan (2001) and Jodhaa Akbar (2008) rejected Hindu nationalist ideas and reaffirmed the earlier nationalism of inclusive India.

Bhaskar proceeded to play a clip of the ending of Jodhaa Akbar, where Akbar (Hrithik Roshan) reaffirms that even though Jodha (Aishwarya Rai Bachchan) is Hindu, she is his wife and commands equal respect despite her religious leanings. Historical accuracies or inaccuracies aside, she emphasised, the film made good use of historical figures to show the idea of a secular, harmonious India. Akbar is portrayed as a figure who respects every religion and fosters unions between Hindus and Muslims. “Movies have been seen as providing resolutions to larger conflicts, and communal tensions, even as their ‘simplistic’ solutions have been critiqued,” Bhaskar added.

Also read:

Muslims in Bollywood’s new offerings

In recent years, films showing Muslims in a particularly negative light have become commercially successful.

Bhaskar’s lecture touched upon recent Bollywood offerings such as Tanhaji (2020) and Padmavaat (2018), where Muslim rulers are portrayed as barbaric invaders. She used posters of the films to illustrate her point. In Padmaavat, Alauddin Khilji, played by Ranveer Singh, and the antagonist in Tanhaji, played by Saif Ali Khan, have similar kohl-rimmed eyes, long flowing locks, and villainous, bearded faces.

“Tanhaji was the trusted general of Aurangzeb, so it [the film] shows how he too imbibed his leader’s ideology in appearance as well,” said Bhaskar. “These films, along with socials like The Kashmir Files (2022) and The Kerala Story (2023), have distorted portrayals of Hindu victimhood to feed into Hindu majoritarian phobias, “ she added.

However, attendees were also eager to know how Shah Rukh Khan’s 2023 films Pathaan and Jawan fit into the legacy of nationalism in cinema.

“Pathaan speaks to the history of cinema and India. It is a film that gives a message because Shah Rukh Khan, who represents the ethos of everyone working together, is named Pathaan. Jawan’s message, of course, was pretty clear to everyone, and both were huge commercial hits.”

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

Tanhaji was not Aurangzeb’s general. Eitger the speaker made this mistake or the reporter. In either case please get your facts right before sermonizing and guiltingbpeople. Just being left is not enough.

Swara Bhaskar married her so called brother bhaiya..

We don’t need lecture from her mother

What else can be expected of Swara Bhaskar’s mother?