New Delhi: Hasty footsteps, murmurs of a muddled crowd, confused faces. At the centre of the chaos were two women—one dressed in a salwar suit and the other wearing a hijab. They caved in as Indian and Pakistani men vengefully violated their bodies. The line between the past and the present blurred as the audience had a deja vu moment.

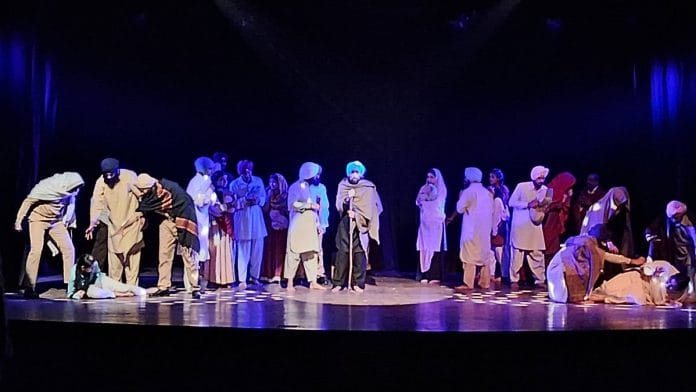

The dimly lit auditorium became a portal to a fractured past. The audience teleported back to 1947, as the thespians on stage enacted the spine-chilling realities of the Partition.

The play—directed by Amar Sah—was performed by the Bela Theatre Karwaan group at Delhi’s Little Theatre Group (LTG) Auditorium on Saturday. The group is the first to enact Khushwant Singh’s novel, Train to Pakistan, in Hindi. They performed it first in 2019, which coincided with Parliament passing the Citizenship Amendment Act.

“Whenever a partition takes place, people are compelled to leave but one can not take their land, livestock, collective histories, the smell of their land…so we have shown the mental state of those people through this play,” Amar Sah told ThePrint.

The play explores themes like displacement and the impact of religious intolerance against the backdrop of the Partition.

The bold depictions of an interfaith romance, communal tensions, and religious bigotry in the 1998 cinematic adaptation of Train to Pakistan by Pamela Rooks had drawn the attention of the censor board and critics. The film was initially met with objections and concerns that it might incite unrest, which resulted in its delayed release.

But the play, despite the violence, leaves the audience with hope through the love story of Jugga and Noora.

A sobering social commentary

As the story unfolded on the stage, the audience sank deeper into the narrative. There were smirks and moments of laughter as the actors candidly commented on the political culture.

The character of Iqbal, whose name means ‘power’ in Punjabi, comes to Mano Majra brimming with idealism. Upon learning that the village has witnessed a murder, he asks with a pale face and a quivering voice, “Where has the party sent me? Did they not have any other place in mind?”

The seated spectators snickered watching the characters’ idealism crumble. They were reminded of the close resemblance between the scene on stage and the politics of the day.

“Iqbal represents politics,” said Sah. The group dramatised the divisionist approach of politicians through dialogues like “Divide and rule” and “we shall not overcome, we shall not overcome… someday,” a reference to the anthem of the American Civil Rights Movement. As the lights faded and the stage was set for the next scene, the audience loudly applauded the creative spin of the director and the on-stage dialogue.

Also read: New play captures Meena Kumari’s great love affair. It wasn’t Kamal Amrohi

Timeless truths

One of the scenes shows villagers being told about India’s Independence from the British Raj, but they seem indifferent.

“Educated people like you will fill the administrative roles once occupied by the British. First we were under British control. Now we are at the mercy of an educated/high ranking Hindustani or Pakistani!” a villager says.

Their words echoed a sentiment which continues to cut across decades: freedom for whom and from what?

Slowly the rhythmic clickety-clack of the railway engine gets louder and time freezes as massacred bodies of Hindus and Sikhs fleeing Pakistan lay on top of one another inside the train. The police officer covers his nose with a handkerchief to examine the scene, while the stench of bloodshed seemed to percolate through the auditorium. This scene was a reference to the Kamoke train massacre of 1947.

The audience was moved by the performance. Many gave a standing ovation, and as the applause faded, some approached the director and actors.

They expressed their admiration for the performance, while others wiped away tears. A Sikh audience member said, “Our grandfather told this story to us, today we saw it in front of our own eyes.”

The play wasn’t just a performance but a bridge between generations, a reminder of the pain still etched in collective memory.

The horrors of the Partition still echo. Religious intolerance, communal violence and elitist political apathy remain unabated across time and borders. Seventy-eight years later, a theatrical adaptation of Khushwant Singh’s novel remains uncannily relevant. A heavy reminder that wounds of history are yet to heal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)

Khushwant Singh never had the courage to pin the blame where it belonged. The partition of India was solely due to the obstinate stance of the Muslim League and the personal ambitions of Mr. MA Jinnah.

Mahatma Gandhi and the Congress fought against it till the very end.

It is a historical fact that the overwhelming majority of Indian Muslims voted for the Muslim league in the elections to the provincial legislative assemblies. Hence, Indian Muslims supported Partition all through.