New Delhi: In the aggressive new Modi’s India, can there be pride of place for an ancient king who rued wars and said sorry? At a time when we ponder over what befits the changing ambitions of the Indian republic better – the Ashokan state or the Kautilyan state – a new book tries to revive the reverence for one of history’s greatest kings.

In recent years, new historiography and politics have been slowly chipping away at Ashoka’s adjective of ‘great’, much like Akbar’s. But, a new book titled Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King tries to locate history within legends and mythologies by tracing his intellectual journey.

“Of all the persons in ancient Indian history, whom would I like to meet, and have a drink with? Ashoka heads my list,” said the book’s renowned Texas-based author Patrick Olivelle, at the launch event in New Delhi. “Ashoka thought out-of-the-box, had intellectual curiosity. He broke the mould on how a king was supposed to be.”

Olivelle’s book comes seven years after Sanjeev Sanyal wrote of how the popular Ashoka narrative of greatness isn’t backed by evidence. In his book The Ocean of Churn, Sanyal questioned if Ashoka was really a pacifist, and if Kalinga had anything to do with his conversion to Buddhism at all.

Olivelle’s book too says “Ashoka was a penitent but not a pacifist. He expresses regret at the carnage but not at the conquest itself. He is reluctant to use force, but he does not abjure it either.”

He had after all carried out a brutal assault on his brothers and other claimants to the throne. And even in the remorse edict, he warns some hostile communities to not provoke, lest they be crushed.

Olivelle’s deconstructs the Ashoka duality dispassionately, without judging him. He refers to the many Ashokas in historiography — from the Ashoka of the inscriptions to the Brahminical text responses of the ideal ruler in the Ramayana and Mahabharata, to the Buddhist hagiographies to the Nehruvian Ashoka.

Also read: It took 40 yrs to find first traces of Ashoka’s Pataliputra. Now, we must find the rest

No edict on ‘caste’

One of the most astounding observations in Olivelle’s book is that the Ashokan edicts make no mention of the caste system, or the varnas. There is complete silence on the subject. The inscriptions about Brahmins do not address them as a sociological or demographic category but rather a religious category.

This observation could upend much of the existing scholarship and popular understanding of caste history.

“The problem with varna is this: where do you get your information from?” the author asked. “Most of the time, one generation repeats what the previous generation said. The only sources about the varna system are written by a small male elite called the Brahmins. We have looked at this enormous landscape, which is ancient India, through this pinhole. We need to rethink (the time of origin of varna order), and Ashoka actually gives us a window and an opportunity to do that.”

This part of the book is mentioned in passing on just one page. But it is bound to spark debate among scholars about whether the absence of evidence can be taken as an evidence of absence.

Also read: Chanakya’s existence, Ashoka’s politics—new book has stories and counter-stories on Mauryas

Resurrecting Ashoka

Ashoka was largely ignored by Indian chroniclers over the centuries but was written about in Southeast Asia, where Buddhism spread. These Buddhist texts about Ashoka were mainly hagiographies written for the faithful, serving as important sources for Buddhist history but less so for Ashoka, Olivelle said. The Kalinga war, for example, features prominently in Ashoka’s own conversion account inscription but finds no mention in Buddhist sources.

It was only in 1837, when British officer James Prinsep deciphered Brahmi script, that a new world of Ashoka opened up. Then Jawaharlal Nehru invoked his legacy and made Ashoka a part of a new nationalist imagination that connected an ancient civilisation to a free nation-state.

But it was Romila Thapar’s first book, Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, which came out in 1961 that “set the modern study of Ashoka on a firm footing”, the Sri Lankan-origin Olivelle said. Thapar sat in the back row listening to his presentation. She too had disputed the theory that Ashoka’s conversion to Buddhism was sudden and happened shortly after the Kalinga war.

For a king so clearly etched in popular Indian memory, scholars have said there is very little information about him. Olivelle calls his book a biography without data.

“Within India itself, there is a black hole of written historical data from the 3rd century BCE,” he said. “We don’t have any Indian sources other than Ashoka himself.” So Olivelle relied on Ashoka’s own writings — around 4,614 words contained in his edicts.

The later Indian corpus of the inscriptional world contained nothing that resembles Ashoka’s inscriptions because “kings were expected to be warriors, not writers”. But Olivelle clarified that his book is not a biography. “It is not possible to write a true biography of Ashoka with the available data. How do you do that when we don’t even know when he was born and when he died? So I have drawn a portrait of a man as it emerges from his own writings.”

Also read: Did the Mauryas really unite India? Archaeology says ‘no’

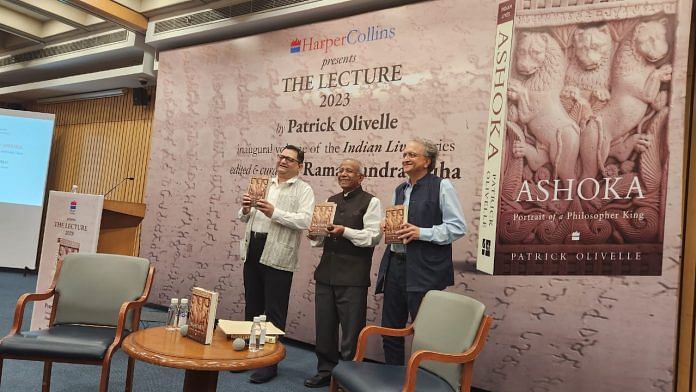

A series on Indian lives

Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King is the first book in the ambitious biographies series called Indian Lives, edited and curated by Ramachandra Guha. The HarperCollins India series will also include books on Kasturba Gandhi, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, Sheikh Abdullah, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, and Raja Raja Chola.

Back when Guha began his career, biographies were just not considered academic enough and were scorned upon by university historians. But he argues that historical biographies as a genre appeal to general readers because “people want to read about lives, and through the lives, they can paint a portrait of society, culture, economy, technology”.

Both the characters—Ashoka and the writer Patrick Olivelle—are the ideal beginning for the series, Guha said.

“To use a cricket metaphor, we are opening with Sanath Jayasuriya.”