New Delhi: It would be a mistake to think that India’s environmentalism began fifty years ago with the Chipko movement. Ramachandra Guha’s new book, Speaking with Nature: The origins of Indian environmentalism, tells us why.

In a return to his academic roots, Guha presents an intellectual history of Indian environmentalism by chronicling the lives and contributions of ten varied individuals — some well–known, like Rabindranath Tagore, Verrier Elwin, and Mirabehn, and some far lesser–known, like JC Kumarappa, M Krishnan, and Radhakamal Mukerjee.

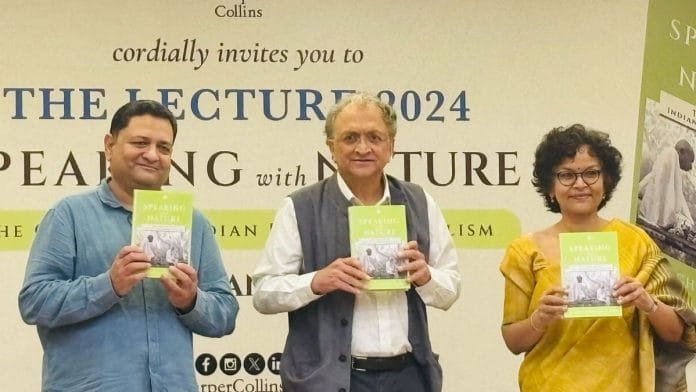

He launched the book on a hazy Delhi evening at the India International Centre (IIC), as the city prepared for the incoming Diwali smog. The poor AQI was as much a part of the conversation as Guha and sociologist Amita Baviskar, Professor of Environmental Studies and Sociology and Anthropology at Ashoka University, who launched the book with him.

“This book was conceived during the time of Chipko, and it’s appearing 40 years later during the time of climate change,” said Guha. “Climate change is a real threat to India and the world. But even if it didn’t exist, India would be an environmental basket case.”

And that is where the work of these thinkers come in — they were anticipating the unthinking emulation of a particular “Western” model of development in India, said Guha, and trying to caution against the impending fallout.

The origins of the book lie in a university archive in the US, where Guha chanced upon pamphlets written by Kumarappa and Mukerjee in the 1930s and 1940s. He was struck by their perspicacity, and the fact that they were anticipating both the Chipko movement and the Narmada Bachao movement — both hallmarks of Indian environmentalism, especially because they were driven by the poor. This was in stark contrast to the American environmentalists and their long lineage, who saw protecting the environment as the preserve of the wealthy and not the poor.

“My book is called Speaking with Nature. All those [Western] thinkers were speaking for nature,” said Guha, in a thirty-minute lecture before his conversation with Baviskar and a round of questions and answers from the audience. “Here were Indians who were articulating a different kind of environmentalism — speaking with nature and marrying notions of equity and social justice with environmentalism.”

His book might have begun as a conversation with Western perceptions of when and where environmentalism originated, but Guha assured the audience he isn’t xenophobic — five Westerners figure in it. And all their work predated the explosion of environmental studies as a discipline, as they were all talking about similar themes sometimes without the vocabulary for it.

“This book is interesting because it combines biography with genealogy,” said Baviskar. “This book is a pantheon of prophets.”

A Guha beyond Gandhi

Baviskar began her conversation with Guha by narrating the famous myth of Ganesha, his brother Kartikeya, and their celestial race around the world. Shiva and Parvati offered their two sons a mango given to them by sage Narada. Whoever could complete three rounds of the world first would win the mango.

Kartikeya set off running around the world, while Ganesha simply took three rounds around his parents — his whole world — and won the mango.

Similarly, and much to the amusement of the audience, Baviskar said Guha’s whole world was Gandhi. “Why did you choose not to make this latest book about Gandhi?” she asked him.

Guha admitted it’s because he’s already written so much about Gandhi, and perhaps he will in the future too. “But I wanted this book to be about little-known people, or little-known facts about well-known people,” said Guha.

Even so, while Gandhi might not have a dedicated chapter in the book, two Gandhians do. JC Kumarappa was “Gandhi’s economist”, while Mirabehn is best known as being a devoted companion to Gandhi. But Mirabehn’s environmentalism is never discussed: she left Gandhi in 1945 and moved to Rishikesh, spending 15 years in the Himalayas. Here she tried to rebuild village society from an ecological perspective by trying to solve water-logging, recognising and teaching people about ecologically valuable plants, and raising awareness about the consequences of rampant exploitation by the forest department at the time.

“She was a precocious and early votary of what we know today as sustainable agriculture,” said Guha.

Similarly, Guha explored the lives of other thinkers who were closely related to developing different approaches to India’s environment.

The Academic Radhakamal Mukerjee, for example, was a pioneer of interdisciplinary research and ecological thinking. He was one of the first thinkers in the world to advocate a closer relationship between natural sciences and social sciences, said Guha, and worked on developing the theory around common property resources — which political economist Elinor Ostrom would win the Nobel Prize for seven decades later.

Novelist KM Munshi is an icon of the Hindu right. But he was also known as an environmentalist. He was the minister of food and agriculture, and it was because of him that both the ecological and economic reasons behind the planting of trees took on new religious dimensions. Promoting the conservation of trees and forests was an important theme throughout Munshi’s life in public service.

“The chapter on Munshi confirmed my view that saffron environmentalism can be very shallow,” said Baviskar, adding that it made her think of subaltern environmental consciousness and the ways in which “religious relationships might actually be a resource to imagine a way of living with nature that isn’t so instrumentalist or disenchanted.”

It’s why India, and Indian environmentalism in particular, is so different from the West, agreed both Guha and Baviskar. India stands as an example for how environmentalism starts from below — because it’s most often driven by the poor, who are most affected by it.

Also read: Cuba beyond postcards. This photographer didn’t want to come back with just ‘travel pictures’

Moving away from the West

India is particularly important for the future of the globe — not because it claims to be the mother of democracy, said Guha — but because of its ecological diversity.

But Indian intellectuals — like Kumarappa and Mukerjee — have been buried by the discipline. It’s a shame, said Guha, because many of them were actually responding to the rampant exploitation of colonialism.

Colonialism played a huge part in the development of every intellectual movement in India. And thinkers like Gandhi and Tagore understood the Western model of industrial development couldn’t simply be copied and pasted to the Indian context. They both saw that global replication of Western structures was not sustainable.

“Tagore recognised that Western imperialism is a system of political domination and economic exploitation, but also a vehicle of ecological destruction,” said Guha. “This is a part of the dialogue today, it’s prophetic of him: he really predicted where India was going.”

At one point, the conversation turned more seriously to the state of India today.

“It’s scandalous that in 11 years the current government hasn’t done anything about the air pollution in North India,” said Guha. “It’s convenient for both the Congress and BJP and whichever other political party to neglect these issues.”

As to why India isn’t seeing a movement like Chipko or the Narmada Bachao Andolan today, Guha had a simple answer.

“From 2004, the Indian state has been suppressing dissent much more, particularly environmental dissent,” he said.

“The state in the 80s and 90s was different, it allowed space for civil society. And the other reason why we don’t see such a movement today is because of the smartphone — which individualises everything, including dissent.”

As with most conversations on the climate, the talk turned to the youth and what they should do to battle an ecological crisis that’s only getting worse.

“I try to stay away from both prediction and prescription,” said Guha, as the conversation wrapped up. “The young are aware, and have a deeper environmental consciousness than when we were young. Something will percolate. So I still feel there’s hope.”

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)