New Delhi: On a mission to decolonise the narrative around the Malabar resistance of 1921, author Abbas Panakkal has relied on oral histories, and other accounts in Ottoman, French, Australian, and Indian libraries. A recent gathering of academics at the India International Centre saw a passionate discussion on the book Musaliar King: Decolonial Historiography of Malabar’s Resistance.

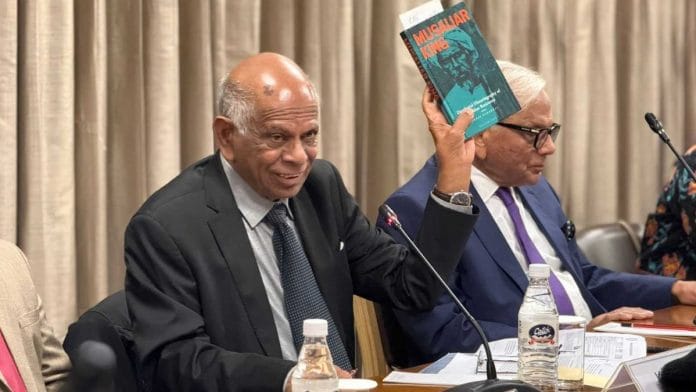

Star-studded panelists of academics and scholars, including former diplomat KP Fabian, Padma Shri Syed Iqbal Hasnain, dean of Jamia Hamdard, Saleena Basheer, Pallavi Raghavan, professor at Ashoka University and professor Syed Jaffri Hussain of Delhi University critiqued and added layers of historical context to Panakkal’s work.

The Malabar Resistance of 1921 is a deeply contested historical event that was born out of the crackdown against the Khilafat movement, and saw an uprising of peasants against the landlords who were primarily Hindus and enjoyed British support. The British historiography reduces the rebellion to a Hindu-Muslim clash, and the resistance hasn’t found a place in the national conversation of revolts against the British colonists.

The author maintains that the peasantry contained both Hindus as well as Muslims and that Muslim houses were also targeted.

In 2021, RSS National Executive Committee member Ram Madhav had said that the Malabar Rebellion was the first manifestation of the ‘Talibani’ thought in India. In the same year, there were also Right-wing protests against celebrating the centenary anniversary of the revolt.

The Hindu Right maintains that the ‘uprising’ or ‘revolt’ was a communal incident, and takes offence to declare one of the leaders of the rebellion Variyamkunnath Kunjahammed Haji as a martyr.

“Historians rely on repositories to provide evidence for accounts. In this project, my repository was also my family, neighbours, and village. When I grew up and learned English, I understood that the British version of the history of the Malabar rebellion was very different from what I had grown up hearing. The popular history was very different from the personal story of the people of this region,” Panakkal said, addressing an audience of academics, students, and historians.

“This book is not just research of 3-4 years, these are stories that I grew up hearing. I have to tell the story of my native place. It is my obligation,” he said.

Also read: Rababi Muslims sang keertans in Golden Temple. Pakistanis called them kafirs after Partition

Oral history or nationalistic take?

Growing up, Panakkal said he had met and acquainted himself with Hindu and Muslim families who maintained an oral history of how Muslims and Hindus both rescued each other during the uprising. He added that the Malabar region, especially Tirurangadi, has a lot of communal peace.

Dr Syed Iqbal Hasnain said that the Malabar or Moplah revolt was an uprising against the British that was “woven with the threads of unity binding Hindu and Muslim to safeguard the throne of Hindu king Zamorin of Calicut.”

“Muslim communities thrived under the patronage of Hindu kings, who they considered protectors who ensured the preservation of Islamic law and culture,” Hasnain said.

Saleena Basheer, while commending Panakkal’s work, didn’t hold back on her critique of the book, which she said could be non-accessible to people who don’t have a lot of awareness about the revolt. She also questioned if the book was over-reliant on oral histories.

“Does the book deconstruct colonial narratives or does it ignore them in favour of nationalistic storytelling,” Basheer asked.

The academics also wondered how radical the decolonial approach could be, as British versions of history are sometimes the only version of historical accounts available in the pre-Partition era, and have to be relied on by historians while writing about history.

Syed Jaffri Hussain, who has written extensively on the revolt of 1857, said the British version of events has to be challenged. He also praised Panakkal’s work. “Indian rebels like Bahadur Shah Zafar, Jhansi ki rani, Rana Beni Madho Singh are described as badmash, this needs to be read between the lines,” Hussain said about British repositories, adding that such language was never used for Australian rebels or Irish convicts.

“The British left but their mentality has stayed with us,” he added.

Hussain maintained that Moplah rebellion oral history needed to be urgently recorded.

“What is accepted by us as an oral history in the realm of Dalit history, women’s history, should also be accepted in terms of Moplah history,” said Hussain.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)