New Delhi: Grandparents are towering figures in every child’s life. But when the grandparents are Mohandas Karamchand and Kasturba Gandhi, they remain greater than life figures well into adulthood.

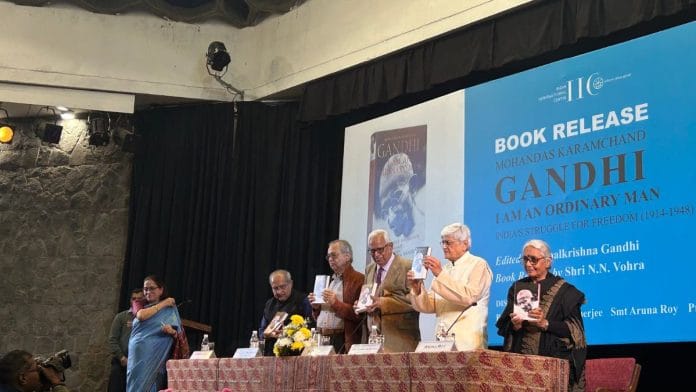

For Gopalkrishna Gandhi (78), the Spanish song Que Sera, Sera (Whatever Will Be, Will Be) is an apt reflection of his grandfather’s attitude toward life. Once, at a gathering, someone asked MK Gandhi to say something about the future, to which he replied: “What is ‘future’? Is it a horse? Say it in Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, or Kannada. Only God can say what is in the future. I am an ordinary man.” Gopalkrishna Gandhi cited this instance from I Am An Ordinary Man: India’s Struggle for Freedom (1914–1948), an autobiography he edited and recently launched at Delhi’s India International Centre.

Gandhi’s complicated legacy has been analysed and written about by historians, poets, playwrights and diplomats. The latest addition to this body of work, however, opens a more intimate and personal window into his life.

I Am An Ordinary Man, picks up from the previous volume, Restless as Mercury: My Life As A Young Man, and chronicles Gandhi’s time in India—from the fight for independence, multiple imprisonments, trials and dreams to the day he was assassinated.

“I speak not as one of his five surviving grandchildren. I am just someone taken by the frankness of his words, the veracity of his message, the scorching sadness of his thoughts, and the rapture of his laughter,” said Gopalkrishna, a former diplomat.

Through the autobiography, he shared a collection of letters, made public for the first time, showcasing Gandhi’s restless aspirations for a peaceful and united India amid the tumult that engulfed India before and after Independence.

“I open any page in this book and I see how remarkable and ordinary that man was, as he called himself,” said Gopalkrishna.

Also read: No point in going back to Nehruvian secularism—JNU prof Nivedita Menon

An ordinary man

Gopalkrishna Gandhi’s stories of his grandfather set the personal within the framework of chaotic events in India’s history. During the Quit India Movement in 1943, Gandhi and wife Kasturba were imprisoned at the Aga Khan Palace Detention Camp in Pune. It was where Kasturba died on 22 February 1944.

Gandhi’s legacy is often intertwined with the lives of his family, particularly his sons, who navigated their own paths under the weight of his influence. For instance, Mahatma Gandhi’s second son Manilal faced unique challenges and expectations, reflecting the complexities of being part of such a prominent lineage.

“She moved her arms for fuller comfort. Then, in the twinkling of an eye, with Harilal, Ramdas and Devadas also beside her, the end came,” Gopalkrishna read from the book. His grandmother, he said, was the driving force behind Gandhi’s simplicity. “She never let him forget that he was an ordinary man.”

His ‘ordinariness’ was brought up by many speakers. Historian, author and panel member Rudrangshu Mukherjee pointed out that Gandhi’s stick and white loincloth were markers of this simplicity.

From 1946 to 1948, Gandhi travelled across India to meet people scarred by communal violence. Mahatma was restless as mercury, said Mukherjee.

“He wasn’t at a negotiating table in Delhi to discuss how India could be carved out into two nation-states. He was among the ordinary people of India. He was an ordinary Indian who led an extraordinary country and an extraordinary group of people,” he added.

The event reignited discussions on the relevance of Gandhi’s teachings in a polarised India. At the discussion following the book release by N.N. Vohra, former governor of Jammu and Kashmir, all the panellists spoke about Gandhi’s legacy today, his impact on our lives, and the “narrative building” against him.

“Gandhi was flesh and blood. He was a human being with the quality of moral fibre, humour, a sense of the ridiculous, who appealed to us as a normal human being,” said activist and Ramon Magsaysay Award winner Aruna Roy who was also part of the panel along with Mukherjee and political scientist Tridip Suhrud.

“In today’s India, Gandhi is seen as an anachronism. When I was young, Gandhi was not in a contentious place, but today he is. You have to argue to even talk about it,” said Roy.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)