New Delhi: It was the Bengal Famine of 1943 that changed everything for MS Swaminathan. As bodies fell and hunger spread, a young Swaminathan walked away from medicine, realising hunger wasn’t a disease to cure but a crisis to prevent. He traded scalpels for seeds, and chose science as his weapon, said Priyambada Jayakumar during the launch of her book MS Swaminathan: The Man Who Fed India at Delhi’s India International Centre on Wednesday.

“He abandoned his medical studies and instead focused on training to become an agricultural scientist. This book takes an attentive look at various other roles he juggled: that of a conservationist, of a crusader, a technocrat, an ardent feminist, a lifelong Gandhian, and a diplomatic collaborator in places as far-flung as North Korea.”

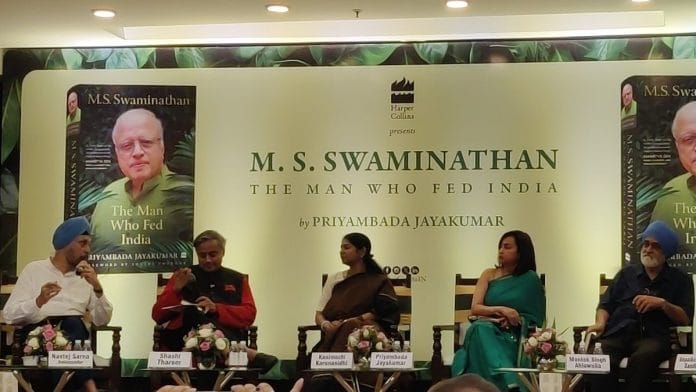

At the launch, the panel — featuring former West Bengal Governor Gopalkrishna Gandhi, economist Montek Singh Ahluwalia, Congress MP Shashi Tharoor, DMK MP Kanimozhi Karunanidhi, and Jayakumar in conversation with former diplomat Navtej Sarna — reflected on Swaminathan’s many roles: not just the architect of India’s Green Revolution, but also a feminist, Gandhian, environmentalist, and quiet diplomat whose science always served humanity.

Amid personal stories and reflections, the panel explored how his vision for an ‘evergreen revolution’, rooted in sustainability, equity, and human dignity, remains urgently relevant today.

The forgotten farmer

Kanimozhi highlighted a crucial issue that was very close to Swaminathan’s heart — the invisibility of women farmers.

“When we talk about farmers in this country, no woman comes to our mind. But 80 per cent of farmers are women. They sow, weed, husk, and carry the crop to market, yet we don’t consider them at all,” she said.

Swaminathan was one of the few leaders who saw that agricultural transformation must include women — not just for equality, but for lasting sustainability. His work in places like Tamil Nadu’s Poompuhar balanced ecological care with economic upliftment. “He believed women think long-term and are natural protectors of the environment,” Kanimozhi said.

Swaminathan’s commitment to sustainability shaped his Evergreen Revolution, which focused on renewing, not exhausting, the land. “His life’s philosophy was essentially a four-letter word: food. Food was life. Food was hope. Food was medicine. And food was dignity,” Jayakumar said.

Tharoor added depth to this vision by emphasising that Swaminathan saw economic growth not as a trickle-down benefit but as something that should rise directly from the soil. He stressed that Swaminathan believed science without social purpose was “almost immoral.”

Gandhi highlighted Swaminathan’s impact beyond agriculture. In 1955, amid the Cold War, philosopher Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein released the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, urging leaders to “remember your humanity, forget the rest.” This sparked the Pugwash movement, committed to using science for peace.

Decades later, Swaminathan served as president of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs — an important but lesser-known chapter of his life that Gandhi emphasised. Under his leadership, Pugwash issued a statement that still stands true today: “The sober reality is that as long as nuclear weapons exist, they will one day be used.” He urged the US and Russia to “take immediate steps to de-alert the more than 1,200 warheads that each country has on high operational alert status, ready to be launched within minutes.”

Also read: India’s agriculture education stuck in Green Revolution mindset

Beyond borders and bureaucracy

Jayakumar’s book tells powerful stories of resilience, hunger, inclusivity, and hope. At its heart, it shows how Swaminathan always put dignity first and never forgot the people his work was meant to help.

Yet, the story of India’s Green Revolution is not without its complexities. While it undeniably rescued a nation from famine and food insecurity, it also ignited ongoing debates about environmental sustainability and the political decisions that followed.

Ahluwalia offered a crucial perspective, defending the revolution’s scientific achievements while pointing a finger at the political aftermath. “What has gone wrong is not the Green Revolution. It is the politics that followed. Subsidising fertilisers to a ridiculous extent, making electricity free, all of that came later. Don’t blame science,” he said.

He pointed to Punjab, once celebrated as the Green Revolution’s success story, but now facing serious environmental problems.

Agreeing with Ahluwalia, Sarna said, “Somehow the message of sustainability got lost. And today when you look at Punjab, people forget that the depletion of water tables and soil degradation are political failures, not scientific ones”.

In a world facing food insecurity, environmental crises, and social inequality, Swaminathan’s vision stands as a beacon — showing that true progress grows from the soil, nurtured by the often-unseen hands of those who work it, with science always linked to social justice.

“As we turn the pages of history we shall be grateful for that one chapter which featured MS Swaminathan, man, messiah or miracle, perhaps all three. But what underlined them all was their undeniable humility, humanity and kindness where he placed dignity at the heart of development and made food security an essential pillar of national sovereignty,” said Jayakumar.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)