New Delhi: In the grand Mughal kitchens where a staggering staff of 400 skilled chefs worked tirelessly, chickens destined for royal feasts were not just any birds; they were treated with the utmost care, fed saffron-infused grains, and given daily massages with musk oil, ensuring that their meat was imbued with rich flavours.

“Akbar wasn’t a foodie; he was only interested in becoming Zill-e-Ilahi (Shadow of God). Jahangir drank himself to death. I don’t quite understand this whole Nawab, kabab, and sharab (alcohol) thing,” food historian and professor Pushpesh Pant said, highlighting that Mughal food became associated with luxury only by the time of Bahadur Shah Zafar.

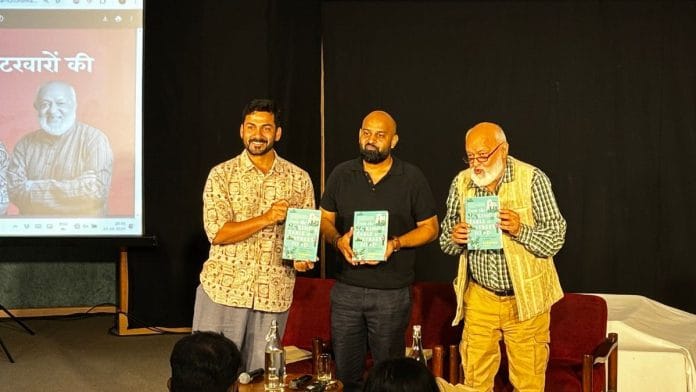

On 14 October, the India Habitat Centre (IHC) hosted the panel discussion, ‘Dastaan Dilli ke Chatkhaaron ki: Food History of Delhi’, featuring Pant, casting director and scriptwriter Ashhar Haque, and chef Sadaf Hussain. Organised by Karwaan: The Heritage Exploration Initiative, the event also saw Pant launching his new book, From the King’s Table to Street Food, which explores Delhi’s rich culinary heritage and its evolution through the ages.

Mughal history and food is a Delhi phenomenon in the popular imagination. But Pant dropped a bomb here and said that the flavours of Delhi aren’t originally from the city; they come from Rampur, Lucknow, Awadh, Meerut, Punjab, Bengal, and Bihar.

“Delhi ka khana hai, par chatkaare bahar ke hain (The food may be of Delhi, but the flavours are from outside),” Pant said.

Delhi food carries its history

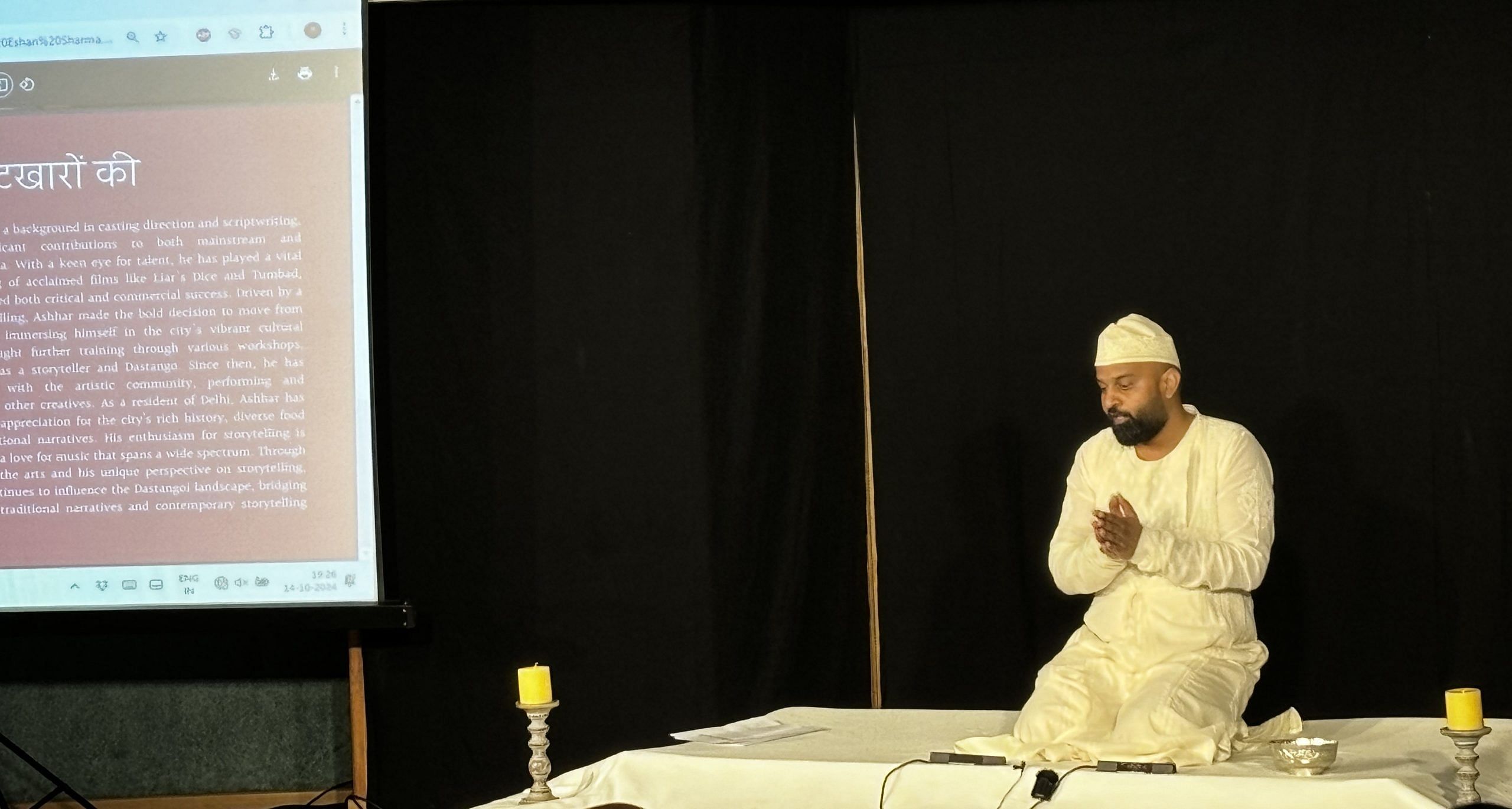

The event started with Ashhar Haque’s Dastangoi performance, which highlighted the fading intricacies of Delhi’s food culture. Haque reflected on the final days of the Mughal dynasty, when the royal chefs were laid off, signalling the end of an era. It was a time when the vibrant sights and aromas of the kitchen—like kheer simmering over an open flame and korma stewing gently—once flourished. Now, these flavours are echoes of a bygone era.

“Dono haathon se thaamiye dil ko, Mir sahab ye sheher Dilli hai (Hold your heart with both hands, Mir, this is the city of Delhi).”

As he recited these lines, Haque captured the chaos and charm of Delhi, where every bite of food carries the weight of history and the thrill of discovery. Each dish tells the stories of the people who created it, revealing the intricate connections between culture, community, and cuisine.

He emphasised that the preparation of Mughlai cuisine was not just a task but a labour of love, a delicate balance between simplicity and grandeur, a slow-burn romance with the food, and an elaborate craft in which every spice was treated with utmost reverence.

“Food from the old days was far superior to what we have today,” Haque said, reflecting on the lost nobility and finesse of culinary practices that once thrived in the bustling Mughal kitchens.

The decline of this artistry and its struggle to retain some of its original flavour mirrors the story of Delhi. Food in the city has lost much of its authenticity, a process that happened over centuries of Mughal downfall, British colonisation, and post-Independence urbanisation.

Haque narrated the tale of a dog that longed to reach Delhi, lured by stories of its famed kababs. However, upon tasting the dish, the dog was disappointed, finding it to be a mere mixture of spices and chilli, and nothing else.

Curious about his experience, another dog tells him, “In chatkhaaron ki vajah se hi to Dilli chhodi nahi jati (These flavours are precisely why one cannot leave Delhi),” reflecting that although the true taste may have faded from Delhi’s food, the stories and the idea of what once existed are precisely why one still cannot leave Delhi.

Also read: Mir Taqi Mir wasn’t a poet of longing like Ghalib. He lived in the resistance space

Chefs and poets

Haque also spoke of the era when the land was overshadowed by Queen Victoria’s rule, with the rule of the Company reigning supreme as the decrees of Bahadur Shah Zafar echoed within the crumbling walls. As the Mughal Empire began to wane, the poets and chefs of the royal court found themselves adrift.

In this shifting landscape, they started to scatter across various regions. The chefs who once prepared feasts for the royal courts started seeking opportunities in the households of affluent families all over India. The royal dishes that had once been exclusive to palaces gradually found their way into the kitchens of everyday people.

Amid this transformation, an individual introduced a dish that would capture the hearts of many: Nihari, derived from the Arabic word nahâr, which means ‘morning’. Traditionally enjoyed during the mornings of winter months, Nihari was crafted from a blend of 12 spices and cooked overnight. It brought royal food to the everyday table, uniting the elite and the common folk.

“Delhi’s uniqueness lies not just in its food, but in its language too, in the way we speak. In every curse, every jest, every mood,” Haque added as he recounted these stories.

He told the tales of Ganje Miya, who was famous for his Nihari and khamiri rotis. Haque described how he would serve his Nihari to customers, singing, “Adrak ki hawaiian, pyaaz ka lachcha, nimbu ka khatta (Waves of ginger, rings of onion, and the tang of lemon),” creating an experience that reflected the essence of Delhi itself.

Also read: Pakistani Hindu girls sing about their dream at IIT Delhi. They want home, govt jobs

Melting pot of Rajus

“Ye sheher aanth-nau baar basa, ujda, aur phir basa (This city has been established, destroyed, and reestablished eight or nine times),” Pant said, as the event transitioned into a panel discussion.

He suggested that ‘Dastaan’ should also explore the foods that came to the city after Independence, brought along by people during and after wars and conflicts as they migrated from different regions, further shaping Delhi’s food culture.

“There is a Raju in every city, and Delhi has its own Rajus. They come from afar, make Delhi their home, and share their stories,” Sadaf Hussain said, highlighting how these Rajus bring with them the flavours and traditions of their native regions, enriching Delhi’s diverse culinary landscape.

“Dilli ke khane se ishq tha, tabhi unhone likha (They wrote because they were in love with Delhi’s food),” Haque said, explaining why writers and poets alike have immortalised the city’s culinary pleasures in their works.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)