Bengaluru: Dalit representation in South Indian cinema is undergoing a radical shift. In Pa Ranjith’s 2022 film Natchathiram Nagargiradhu, Renee, a Dalit woman with striking blue hair and a septum ring, pointedly asks her partner, Iniyan—a staunch Brahmin—“Will you eat beef?” But the scene’s framing almost makes it look as though the question is directed at the audience. This moment is part of a growing movement where filmmakers challenge the Brahminical gaze in South Indian films.

The scene caught the attention of Apeksha Singegol during her PhD research on Dalit representation in South Indian cinema.

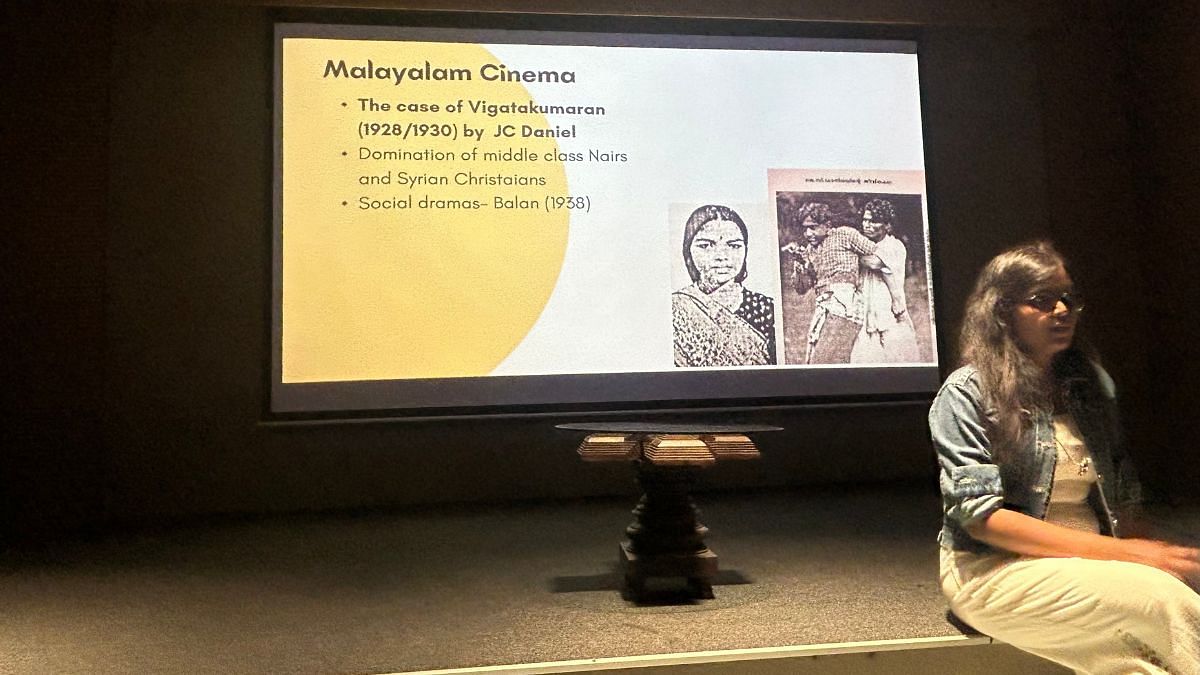

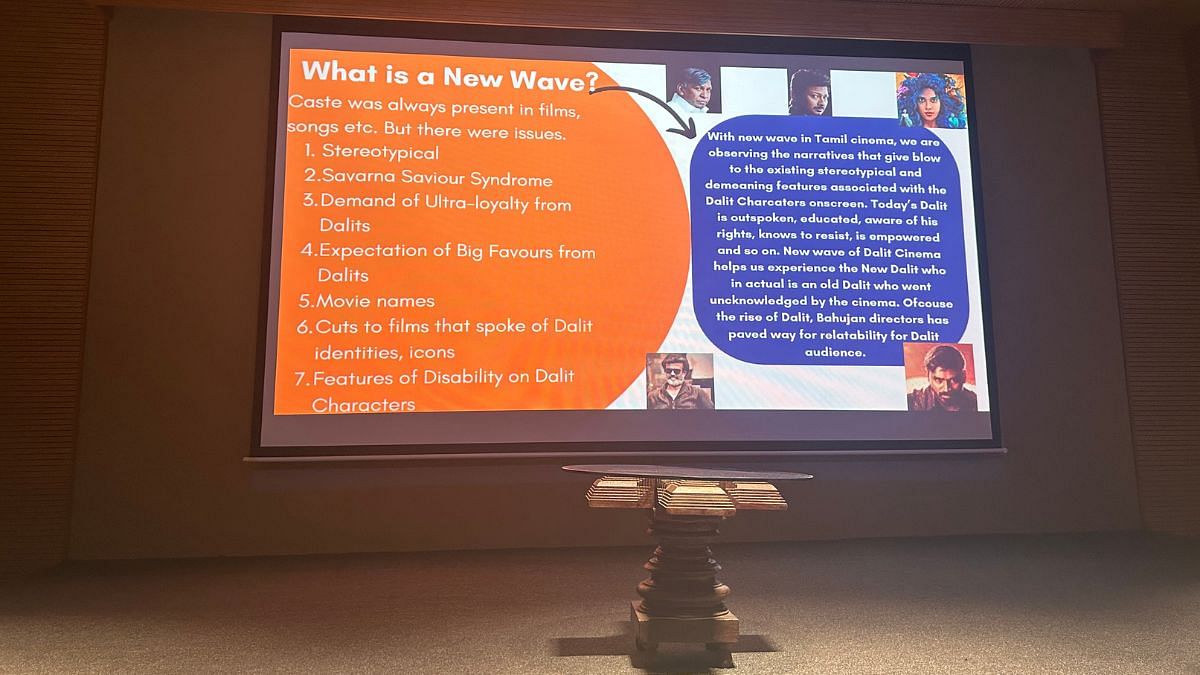

“A new wave of Dalit cinema has emerged over the past decade. It helps us experience the ‘new Dalit’ who, in reality, is the old Dalit that went unacknowledged by cinema,” said Singegol, a research scholar at Christ University, Bengaluru. Speaking at Atta Galatta bookstore in Bengaluru on 25 January, she examined Dalit representation in South Indian cinema, especially their portrayed in Tamil, Malayalam, and other South Indian films since the 1950s.

Directors like Pa Ranjith, Mari Selvaraj, and Gopi Naynar are challenging the Savarna gaze—the upper-caste lens that has dominated film narratives. Rejecting stereotypes of Dalits as downtrodden or disabled, their films, such as Kaala (2018) and Thangalaan (2023), recenter Dalit agency and dignity.

For instance, Pa Ranjith’s Thangalaan (2024) focuses on Dalits who lost their lives while mining gold for the British in Karnataka’s Kolar Gold Fields. For Singegol, the film’s message is clear: The gold we wear is stained with the blood of Dalits.

The film, she noted, focuses on reclaiming the Dalit identity, much like Natchathiram Nagargiradhu, where Renee, anassertive Ambedkarite, breaks up with her boyfriend Iniyan after he hurls a casteist slur during an argument.

“Today’s Dalits are outspoken, educated, empowered, and aware of their rights,” Singegol said. And it’s their stories that Dalit filmmakers are telling.

Also read: Indian films and OTTs see money in Dalit stories. But watch out for symbolic violence

What dictated portrayal of Dalits in South Indian films

As a Kannadiga, one of the first Kannada films Singegol watched was Vasantasena (1941), one of only two pre-1947 Kannada films preserved today. Vasantasena’s Brahmanical narrative became a template for other Kannada movies released at the time, Singegol said.

Directed by Ramayyar Shirur, the film follows a wealthy courtesan who falls for Charudatta, a Brahmin portrayed as noble who loses all his wealth to charity and makes sacrifices for others.

“I was very upset when I watched this movie. Brahminical perspectives came to heavily dominate Kannada films and the templates were the same. The hero, saviour and noble, was always a Brahmin,” Singegol said. Such caste identification wascovert—especially in the form of names, professions, and personality traits given to the main characters.

Charudatta’s poverty in Vasantasena was due to his own charitable nature. Similarly, in B Dorairaj and SK Bhagavan’sKasturi Nivasa (1971), matchbox factory owner Ravi Varma (played by Rajkumar) helps his employee Chandru financially and also sends him abroad for training. “Chandru speaks in a dialect of Kannada that is heard in Hassan where the majority of Vokkaligas reside. So the movie was trying to show that Ravi was a noble who helped a Vokkaliga under him even though he was going through his own difficulties,” Singegol pointed out.

Even films tackling taboo topics like prostitution, incest, and adultery retained caste hierarchies. Puttanna Kanagal’s Gejje Pooje (1969)is one of the first movies in South India to talk about the Devadasi system—the practice of dedicating girls to Hindu temples, often leading to exploitation.

“But even in this movie, the woman forced into the Devadasi system is a Brahmin, which ignores the lived realities of Dalit women,” said Singegol.

The discussion then swiftly moved to how this Savarna gaze was also visible in films of other South Indian languages. Untouchability and temple entry movements were mentioned in passing and never addressed in depth in Malayalam and Telugu films as well.

The 1938 Telugu-language film Malapilla is one of the first social dramas that deals with these issues in pre-independent India. A Dalit woman and a Brahmin man (also the son of a head priest) elope from the village. This unfolds while a group ofDalits is trying to enter the temple headed by the same priest. The movie ends on a positive note—the protesting Dalits save the priest’s wife from a fire, and in turn, he welcomes his son and his wife.

What this movie does is reinforce the stereotype, said Singegol.

“Dalits were only allowed to enter temples after they showed kindness to the upper castes in their village. They had to be kind to their oppressors—only then could they emerge victorious.”

Real-life caste violence, such as the Karamchedu and Tsunduru massacres of Dalits in Andhra Pradesh, found no representation in films of the time. In 1985, a large group of Kammas (a dominant caste), armed with deadly weapons, killed six Madiga men and raped at least three women in Karamchedu. In August 1991, a mob of upper-caste men lynched eight Dalit men in Tsunduru.

Also read: 2021 was the year of anti-caste cinema — from Jai Bhim to Karnan

New wave: Dalit filmmakers redefining South Indian cinema

Tamil Nadu has been at the forefront of Dalit representation in cinema. Tamil films hint at anti-caste elements due to the state’s Dravidian movement. However, with the turn of the millennium, a new wave of filmmakers from the heartlands has emerged, amplifying the voices of the oppressed.

“Films are named after Dalit characters, shot in places relevant to the community, and are more relatable to a middle-class audience,” Singegol said.

One such movie directed by Pa Ranjith is named after the Dalit protagonist—Kaala, played by Rajinikanth, who fights for land rights in the Dharavi slums of Mumbai. The hero is a Dalit. He is the one who protects his people and resolves disputes. Kabali (2016) takes its title from the historical surname used by Dalit fishermen. Even the book that Rajinikanth reads in the opening shot of Kabali is important in the discourse about caste—My Father Baliah by YB Satyanarayana, a biography of the writer’s experience as a Dalit in Telangana.

“As he is himself a Dalit, most of Pa Ranjith’s films have given back the agency to the community that was long theirs,” she added.

Similarly, in Mari Selvaraj’s Maamannan (2023, Tamil), the Dalit hero is not portrayed as docile or powerless but is an MLA who fights for social change. The movie even addresses the caste-based discrimination within Dravidian politics.

In the worlds of these directors, it’s not just about the human characters, Singegol pointed out.

“Animals like pigs and donkeys are considered dirty and hence equated to Dalits in historical texts. But Dalit filmmakershave used these animals as power icons in their films,” she said. In Maamannan, one of the protagonists played by Udhayanidhi Stalin rears pigs. In one of the scenes, he paints a piglet with wings, signifying the transformation of the creature often associated with filth into a symbol of freedom.

“These are the kind of movies that you can’t watch with popcorn in your hand, comfortably in your seats,” said Singegol, quoting Selvaraj. This shift in storytelling marks a significant transformation in Dalit representation in South Indian cinema, reclaiming narratives that were long sidelined.

(Edited by Prashant)

Such a one sided ill-researched write-up. Firstly, none of the episodes of dalit oppression and violence were inflicted by the brahmin community but yet, your headline captures it as Brahminical gaze, making your hidden agenda very silly and blatant. Secondly it’s this minority community that is shown in poor light, made fun of and poked in every tamil movie that is released ! Thirdly, look at movies from Balachander and others which take on the issue of casteism and portray them well..wish some more research goes into further topics and hope the news minute can distinguish between the rice and the chaff !

Brahminism? Why are we connecting dots that are drifting away faster than our galaxies?

Both these massacres were done by roling rural land owners, and yet the focus is Brahmins who are less than 5% people and one of the least land-owning or violent or politically controlling classes. Every Brahmin I met is self made hard working employee or of educated service class, which I cannot say for my so called OBC rulers of the nation.

Why are people stuck centuries ago and millenia ago where they might have helped design the caste system, wherein they have been economic paraiah and social scapegoats for last few centuries?

Brahmins should RBC – real backward class of today.

People are stuck in Ambekar and Marxist imaginations disconnected from reality. Brahmins of today have no reservations or support from the governance systems, continuously swim upstream, and being the easiest scapegoats for all the oppression and discrimination that others do, who ironically are the political leaders with so called backward classification. No oppressed people fight against them because that will actually have blow backs for God’s sake!

Move on to the reality, people! Brahmin bashing oughtta run out of fashion at some point!

so anisha

lets take it same way and how about starting to question the great as god representation of our reddy background people in the telugu movies ?

all u find is brahmin . hahahahahahaha, lets self interospect abt our caste while we will

but u wont and hence this choice