New Delhi: Poet, literary critic, translator, and curator Ranjit Hoskote was asked a seemingly mundane question—why read an anthology? They contain texts that have simply been reproduced in a different form. What’s new? He answered by way of a careful bypass.

“Do we really read anthologies because we want to read something new? I found myself thinking of an anthology as a kaleidoscope, a set of pieces,” he said at the Delhi release of Ten Indian Classics, an anthology of some of the subcontinent’s most seminal literary works.

“It is through anthologies that so much of our literature has been passed on.”

‘Classics are sources of renewal’

Ten is a paltry number for a country with a literary tradition as bountiful as India’s. But even so, it encompasses, according to Hoskote, over 2,000 years of composition and writing in South Asia. It traverses and transcends time and space.

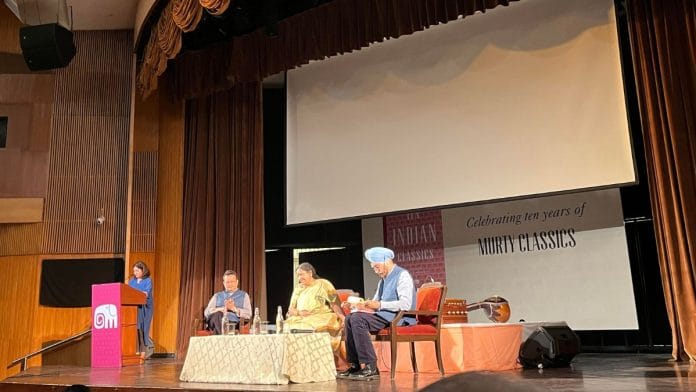

In conversation with translator Vanamala Viswanatha and former US ambassador Navtej Singh Sarna at India Habitat Centre, the evolution of language and literature was discussed through a prism that most would consider stationary—Indian classic writing.

The book carries a tonne of cultural weight. It consists of a section of Philip A Lutgendorf’s translation of Tulsidas’ Ramcharitmanas, Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s version of Mir Taqi Mir’s poetry, Guru Nanak’s poems in the Guru Granth Sahib by Nikky Guninder Singh, and the verses of Bulleh Shah by Christopher Shackle.

Each of these classics, which aren’t necessarily unfamiliar territory for a non-academic audience, has been made readily available—all in English. It’s a testament to the power of translation and the rich oeuvre of translations that now exist in India.

“A major plethora [of Indian literature] remains untranslated and therefore unknown. A work such as this is cause for jubilation,” said Indira Viswanathan Peterson, the English translator of Arjuna and the Hunter, a Sanskrit epic.

But the question to Hoskote still stands. Why read an anthology? And it was attested to by English-to-Kannada translator Vanamala Viswanatha.

“There’s no ready-made readership [for the classics]. We have to tell people, look at how beautiful, how relevant this is,” she said. “There’s a nascent interest in the ability to read the classic but not in the understanding of a text.”

However, she added, there’s a pattern that emerges through the relatively small audience that are true-blue readers of classics. Translated copies of texts sell the best in their home states. Her English-to-Kannada translations have found their largest audience in Karnataka itself.

The discussion also touched on a truism that made the audience, which appeared to consist of general readers, heave a sigh of relief. There is no Indian who has read or performed the critical additions of either Valmiki’s Ramayana or Tulsidas’ Ramcharitmanas. Despite the narrative’s ubiquity, they’ve seeped into the mainstream in a changed form—another sort of translation.

“The classics are sources of renewal. They continue to be with us, but we have to go and find them,” said Hoskote. “We seek plentitude. They continue to compel us with their complexity and beauty.”

Also read: Taslima Nasrin’s Lajja has a ‘go to India’ message. As a play now, it’s a bold nod to CAA

Translate at your own peril

The questions which wrapped up the discussion were primarily practical—about the logistics of translating as well as the career trajectory.

“You do it at your own cost and peril. In the morning you are one person and in the evening you are another,” said Viswanatha, who has worked as an English teacher for four decades. It’s only after she peels off layers of the day that she becomes a translator.

An audience member asked why so many translators, particularly those who’ve participated in the anthology, are from the Western world. According to Hoskote, in North American and European academia, “there was, for the lack of a better word, a great deal of investment in these disciplines.” Whereas, he said, in his own alma mater, Mumbai’s Elphinstone College, the number of language departments has been trimmed massively—the decay of classic literature.

There was silence as Viswanatha read a section of a poem on King Harishchandra. The audience was spellbound—whether it was English or Kannada, not a single murmur was heard.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)