New Delhi: Renowned multilingual poet Amir Khusrau championed Hindavi—an early form of Hindi—over Farsi and Turki. An act of literary defiance, this showcased his deep connection to Indian culture despite his Uzbek roots. He hailed Hindavi as one of the subcontinent’s magnificent contributions to the world, alongside music, astronomy, chess, Panchatantra, and zero.

“As we examined the manuscripts, we were struck by the beauty that emerged from cultural differences, from plurality and interactions,” Niharika Gupta told ThePrint, talking about the power of language and stories to connect, create beauty, and inspire wonder. She has curated the exhibition, ‘Manuscripts and the Movement of Ideas across Asia’, inaugurated at IIC Annexe on 17 October.

The exhibition explores how Indian texts and narratives have influenced cultures across Central, West, and East Asia throughout history. It is part of the SAMHiTA (South Asian Manuscripts Histories and Textual Archives) project, which is steered by Sudha Gopalakrishnan—executive director of the International Research Division at IIC—and supported by the Ministry of External Affairs. SAMHiTA aims to create a digital repository of South Asian manuscripts housed in libraries outside India.

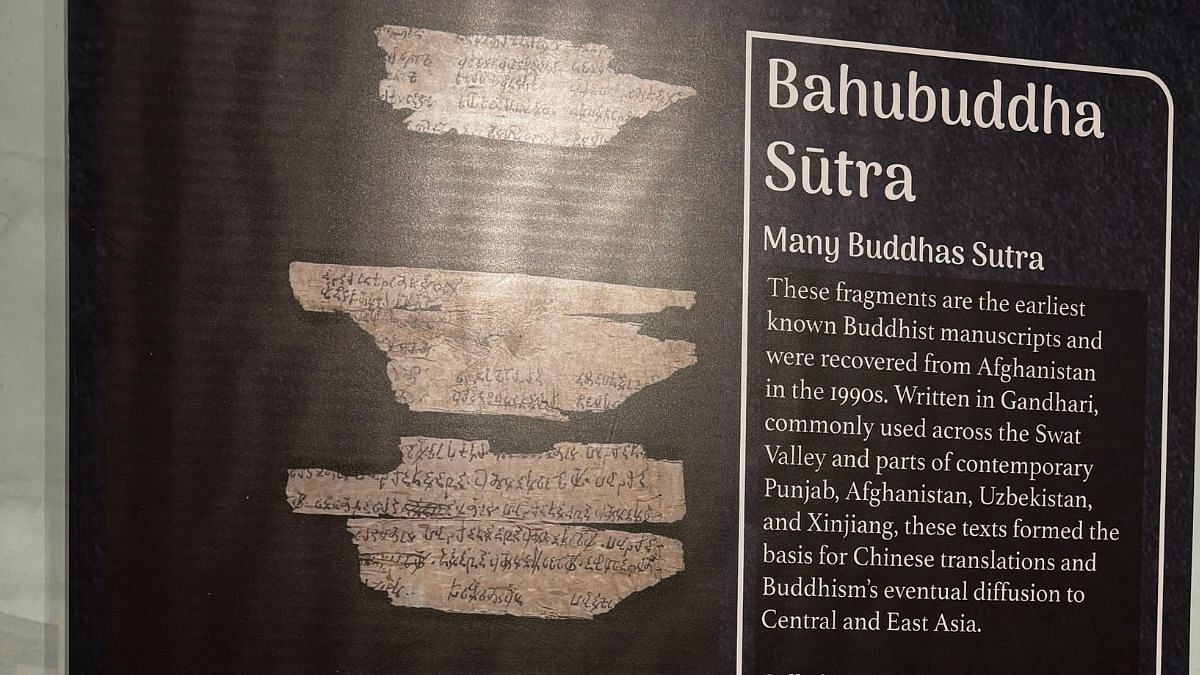

Conceived by Gopalakrishnan, the exhibition features selected works such as 2,000-year-old birch-bark scrolls of Mahayana Buddhism discovered in Afghanistan in the 1990s, now housed at the Library of Congress.

“Some connections are very important and define our identity as much as differences. Transnationalism binds us together,” Gopalakrishnan said, highlighting how shared narratives interlink diverse cultures across Asia. “Literature and culture show that there is so much beyond borders.”

Asian manuscripts in a cosmopolitan world

As Buddhism began its journey from the plains of India to the mountains of China, it did more than just travel; it underwent profound transformations. Originating as rich oral traditions, Buddhist teachings gradually shifted toward written scriptures.

As Indian texts transformed during their travel, the essence of Indian Buddhism blended with Chinese influences.

“Donald Lopez and Jacqueline Stone have written of how Chinese translators embraced concepts that resonated with them, such as non-duality and the bodhisattva’s perfectibility,” Gupta said.

The Saddharma Pundarika Sutra, in particular, became immensely popular in East Asia. Commonly known as the Lotus Sutra, it tells the story of a poor man who unknowingly has a jewel sewn into his coat. When he learns about the jewel, he realises that he possessed what had been seeking all along. The jewel symbolises the potential for Buddhahood within every individual.

Nichiren, a prominent Japanese monk, captured the essence of the text in his mantra, “Namu myoho renge kyo (I take refuge in the Lotus of the Wonderful Law).” Chanting the mantra remains the principal practice of Nichiren Buddhists today.

“Their global influence reflects how Buddhist concepts have integrated into people’s lives, inspiring art and fostering dialogue with traditions like Vedic thought and Kashmiri Shaivism,” Gupta said.

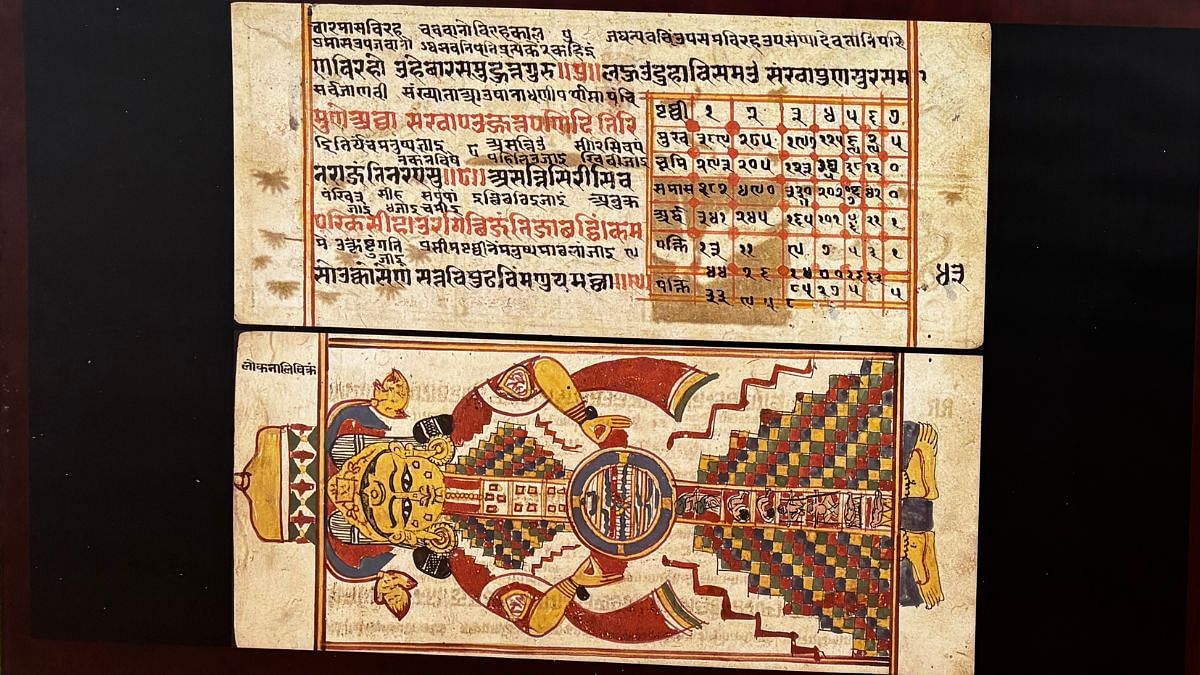

South Asian manuscripts dating back to the sixth century such as the Jain text, Sangrahani Sutra, reveal that the concept of transmigration has been deeply rooted in philosophical and spiritual traditions for centuries. The Langhu Sangrahani Sutra delves into the structure of the universe by describing the three lokas (worlds): Urdhvaloka (the realm of gods or heavens), Madhyaloka (the realm of human existence and spiritual activity), and Adholoka (the realm of demons).

In Vedanta philosophy, jeevatma (soul) is seen as a reflection of Brahman, the ultimate reality or divine force. Brahman is thought to have a desire and will to manifest itself in the world through the individual soul. When Farsi translators engaged with this concept, they emphasised ideas that made sense within Islamic thought, often focusing on the aspects of divine will (irada).

“This reveals the pluralistic nature of our world, showing how cultures continually respond to external influences through trade, travel, and education,” Gupta said.

Also read: Lithuanian ambassador shows how one artist’s work connects the Baltic country, France, India

Modification of Indian narratives

In the Mahabharata, Yudhishthira is told about the romance of Nala and Damayanti, which faces numerous challenges including an encounter with the demon Kali. This tale journeyed from the ancient Sanskrit epic Naishadha Charita to the court of Mughal Emperor Akbar, where it was reimagined by the 16th-century Persian poet Faizi.

“This modification symbolises the dynamic nature of storytelling across cultures, where narratives transform to resonate with new audiences,” said Arpan Guha, the exhibition’s research associate.

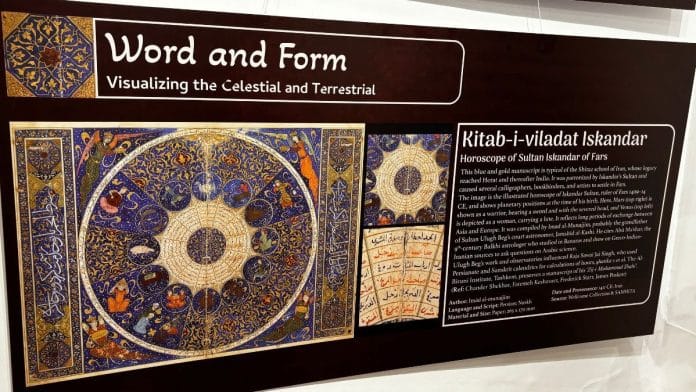

Many Indian stories, including Nala’s, circulated between present-day Uzbekistan and Iran. Chander Shekhar, a retired Farsi professor and former director of the Lal Bahadur Shastri Centre for Indian Culture in Tashkent, guided the curation of Farsi manuscripts for the exhibition.

Interestingly, the Naishadha Charita focuses on the themes of beauty and desire, while Faizi’s version takes the story up to Nala’s death.

“Sanskrit dramas never end in tragedy,” said Gopalakrishnan. “Even if death occurs, there is rejuvenation after. This contrasts with the Greek celebration of tragedy and catharsis.”

Urfi Shirazi’s Persian poem, Qasaid-e-Urfi, illustrates how, during the 16th and 17th centuries, the Mughal Empire became a hub for poets from West and Central Asia. It offered hospitality and recognition to artists such as Shirazi, who was celebrated for his qasida—a poetic form traditionally used to praise kings and patrons.

A miniature painting at the exhibition shows him presenting qasidas to Prince Salim, who later became Emperor Jahangir.

This movement resulted in the poetic innovation known as “taza gu’i” or “fresh speech”. This led to a widespread reimagination of classical themes and metaphors, infusing poetry with new experiences and ideas to keep it vibrant and relevant.

Gupta noted that texts such as the Lotus Sutra and the Adhyatma Ramayana have historically offered comfort during turbulent times. Communities always turn to literature to find meaning amid instability.

Many of these manuscripts end with a verse, “bhagnapristha katigriba baddhamushtha adhomukha,” where the scribe makes a heartfelt plea to readers to care for the manuscript he has copied out. It vividly describes the scribe’s broken back, aching waist, and bowed head.

Each manuscript not only bears the weight of its content but also embodies the tireless work and commitment of those who created and transmitted it—and later preserved it from erosion over centuries.

The exhibition will end on Saturday, 26 October.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)