Five years after the Archaeological Survey of India wrapped up the now famous and paradigm-busting Keeladi excavations in Tamil Nadu, the arduous work of preparing detailed drawings of the findings from the first two seasons of the dig is finally underway.

Crucial to this documentation of over 5,000 artefacts—dating back to 2,300 to 2,600 years ago—is the work of a draughtsman, a person skilled in making technical drawings and illustrations.

But archaeologists say they are in short supply these days. For this task, A. Palanivel, a 70-year-old draughtsman who retired from service at the ASI’s Chennai Circle office in 2012, was enlisted especially for his “fine arts” skills. He has, in fact, been in high demand.

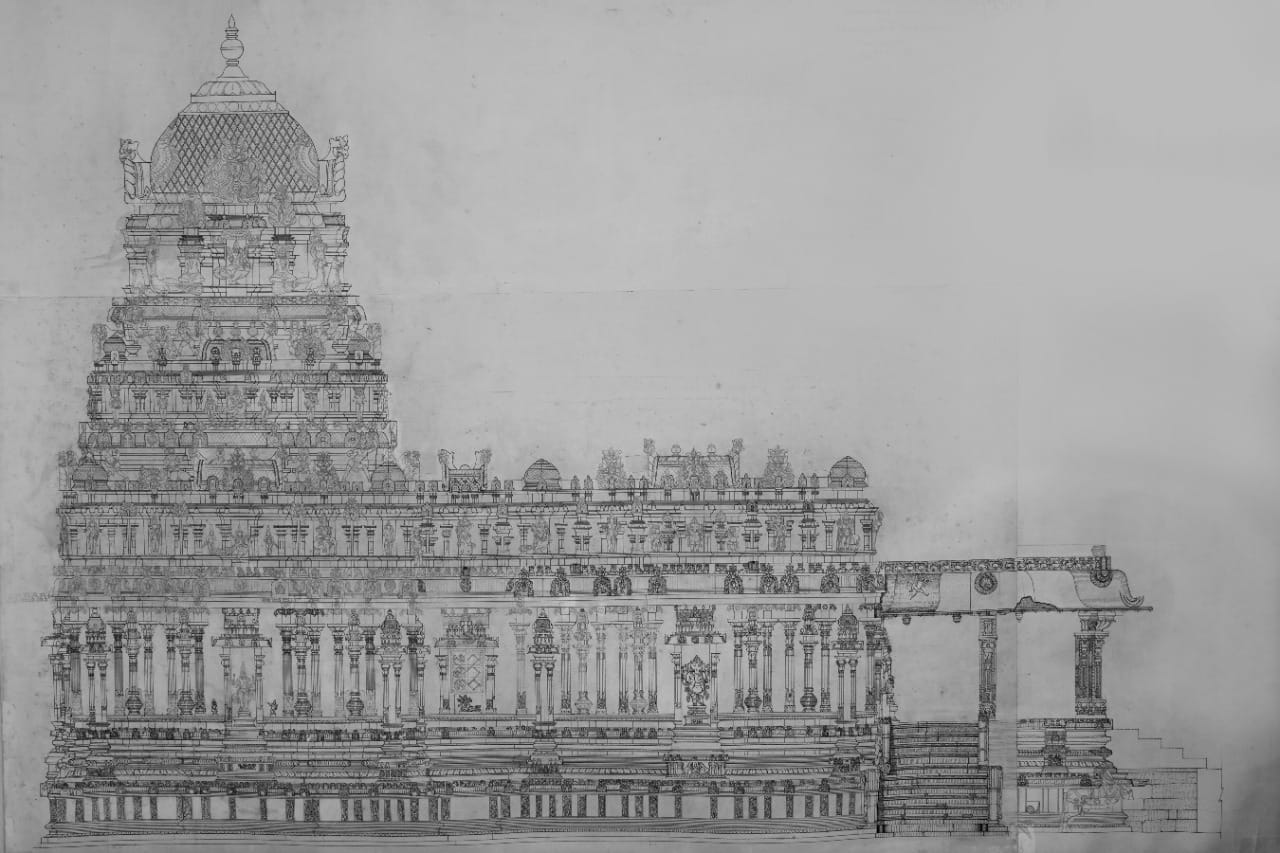

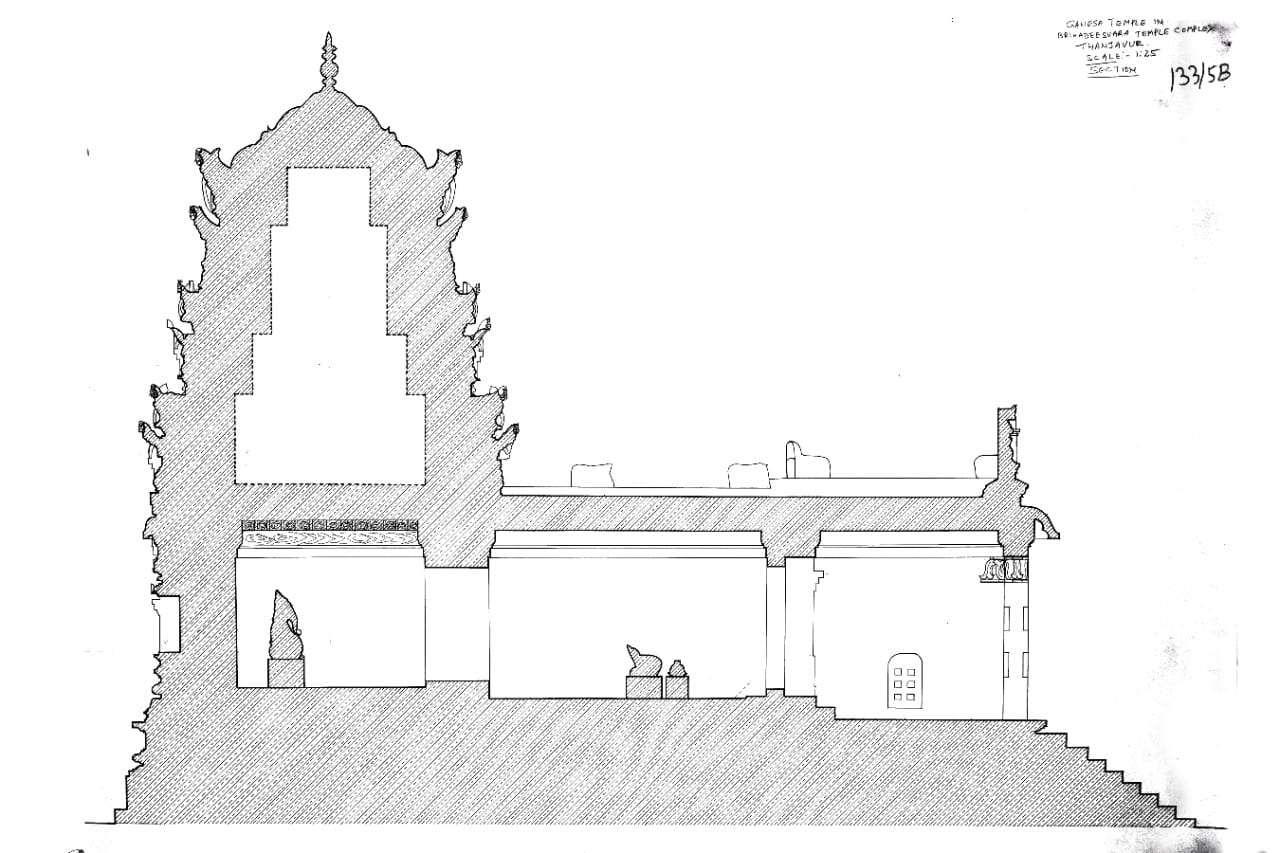

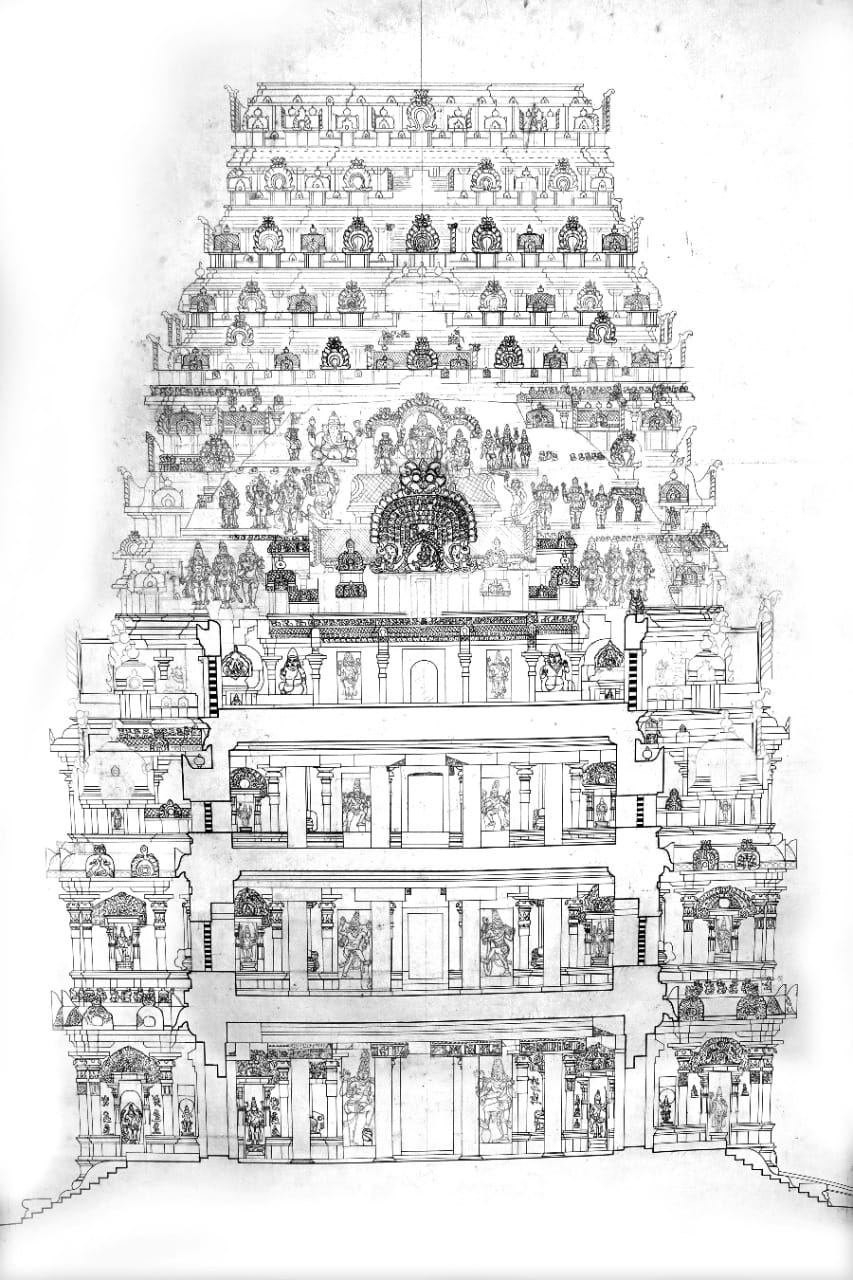

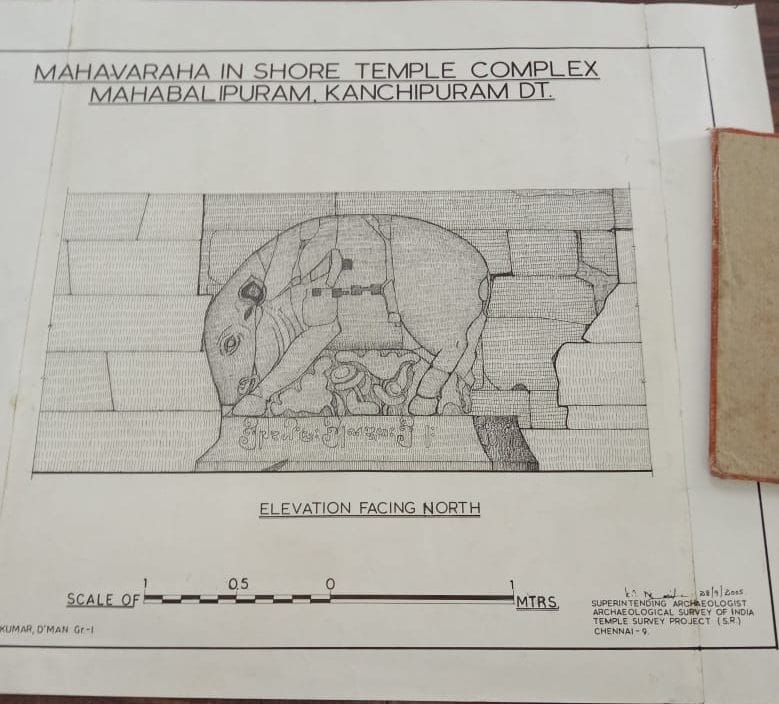

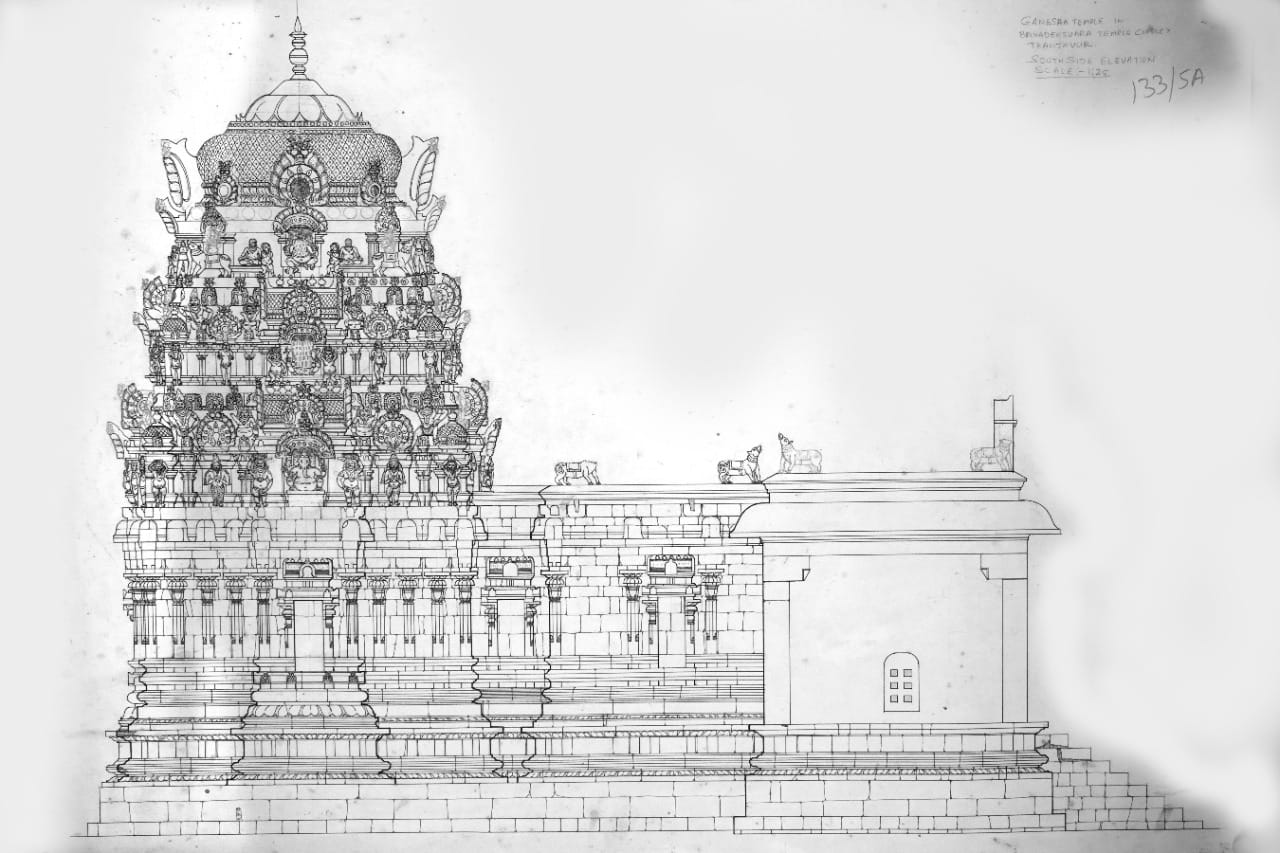

Palanivel was allowed to stay “retired” for just three months over the past decade, constantly roped in by a line of superintending archaeologists to work on prestigious projects. They ranged from the Kondapur excavations in Andhra Pradesh to the stunning Brihadeeswarar Temple in Tamil Nadu. In the latter, there was a crack in the Rajagopuram (the tallest temple tower) which his drawings helped plan for restoration work.

Now, his skills are crucial to documenting Keeladi. His drawings will help build the archaeological narrative of the excavation project that has disrupted existing notions of ancient Indian history like no other in recent years.

The site, which showcases a vibrant urban settlement, indicated a possibility that the southern part of India may have urbanised around the same time as the Gangetic plains.

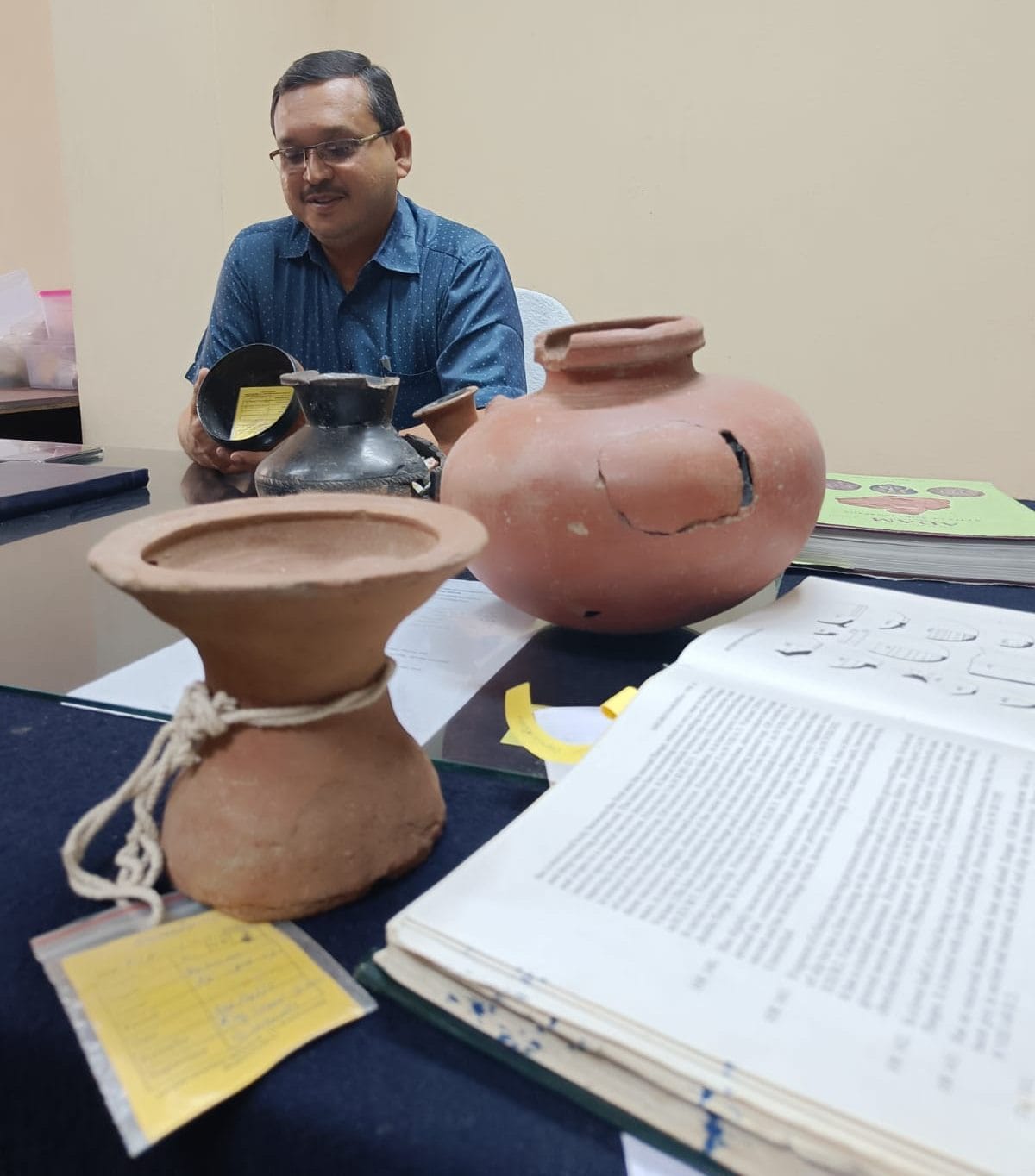

An advanced carbon dating process placed the settlement between the sixth and third century BCE. The 5,800 artefacts excavated between 2015 and 2017 include pottery with Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions and graffiti marks, ornaments, engravings on bones and several antiquities.

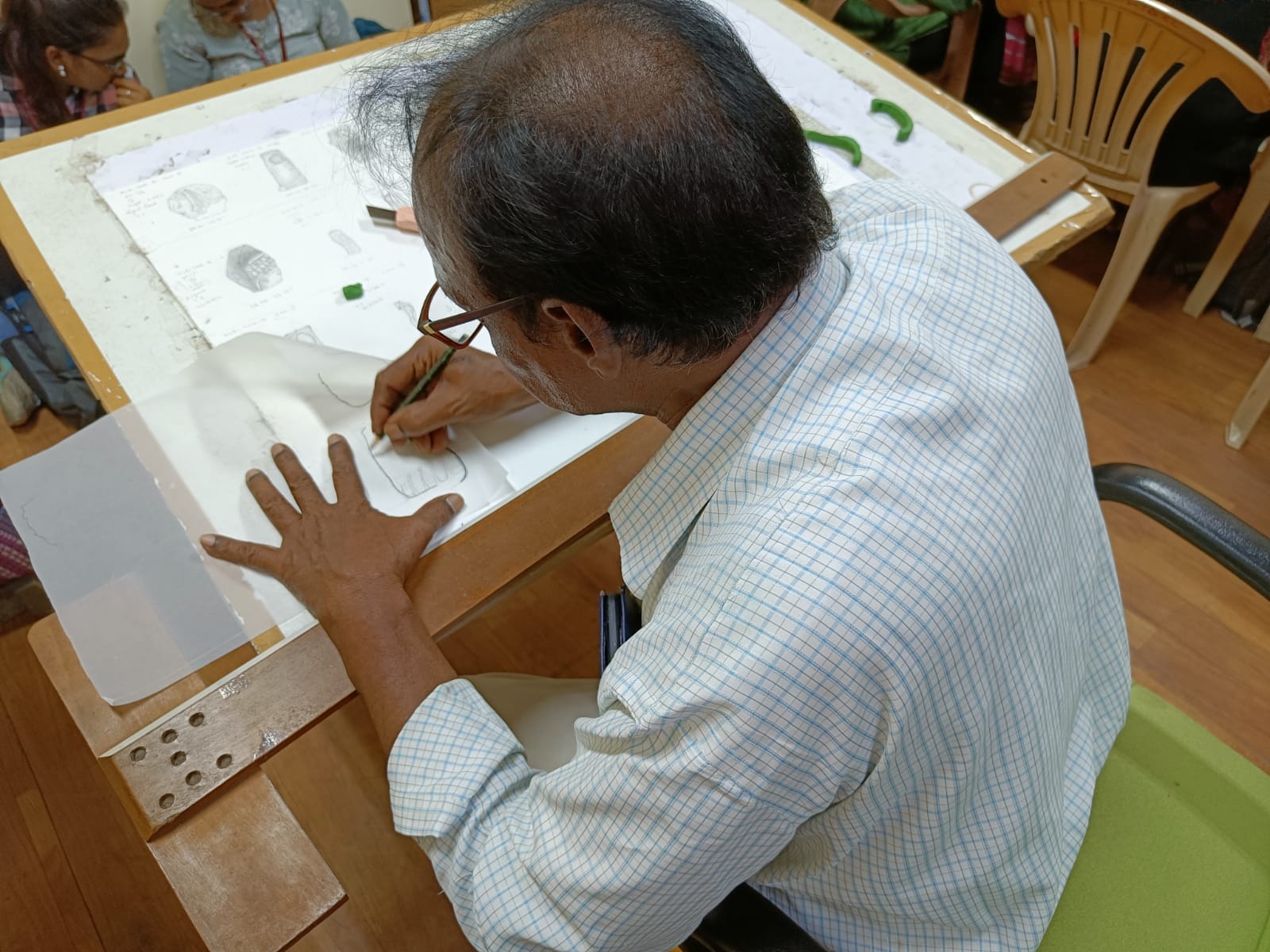

Last week, Palanivel sat bent over a large chart paper tracing the contours of a terracotta figurine’s right foot. The first two seasons of the Keeladi excavations concluded in 2016 and now the documentation work must catch up.

It was a ground-breaking discovery in 2014 by a team put together by ASI’s superintending archaeologist Amarnath Ramakrishna, who is credited with discovering this Sangam-era site. The discovery itself, however, turned controversial, which saw Ramakrishna transferred out to Assam and the ASI abandoning the project altogether. Though an interim report was filed at the time, work on a detailed report began six months ago when Ramakrishna returned to Chennai to head the temple survey project.

From 2018, the site was taken over by the Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology and is currently in its eighth season of excavations.

Also read:Iron Age in Tamil Nadu dates back 4,200 years, ‘oldest in India’

Adventurous past, interesting present

Palanivel’s work at Keeladi involves a painstaking reproduction of the artefacts. It’s perhaps some of the oldest relics he has handled to date. “However beautiful the artefacts are, I have to draw them exactly right and cannot make them more beautiful,” he said.

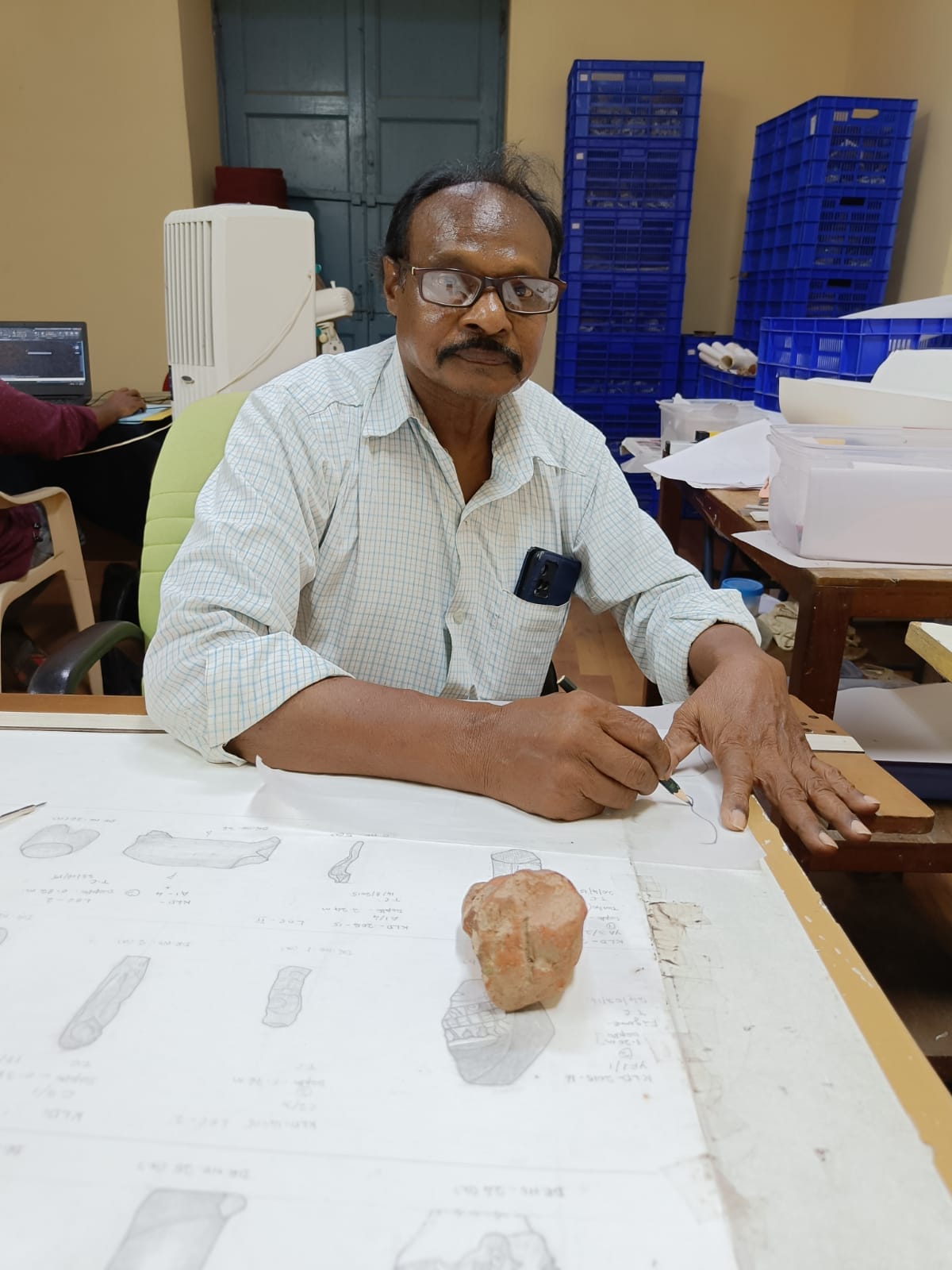

In the last six months since he started work on the project, Palanivel has lost count of the large and small terracotta pots he has drawn. But the rolls upon rolls of white chart paper in his workspace are an indicator of how many artefacts he has painstakingly illustrated. Behind him are neatly stacked blue crates holding these ancient relics all tagged with reference numbers. Among them is an entire collection of lamps.

His drawings will be scanned and produced into a thick folder with clear descriptions of each artefact, the depth from where it was unearthed, and possible interpretations over what it could be. The report will serve as a solid document of the Keeladi excavations and will help make comparisons with other excavations sites.

Every day, Palanivel spends roughly 6-7 hours at his desk. Though he handles objects that are thousands of years old, he focuses on the present. “Every drawing I do, I do it with interest. There is no such thing as this object looks pretty so I should draw it better,” he said.

In a way, the black and white recreations detailing every contour, crack and crease are works of art. Though Palanivel doesn’t see it that way. “I know that the shards and other artefacts I handle are priceless, but getting the details right is very important,” he said.

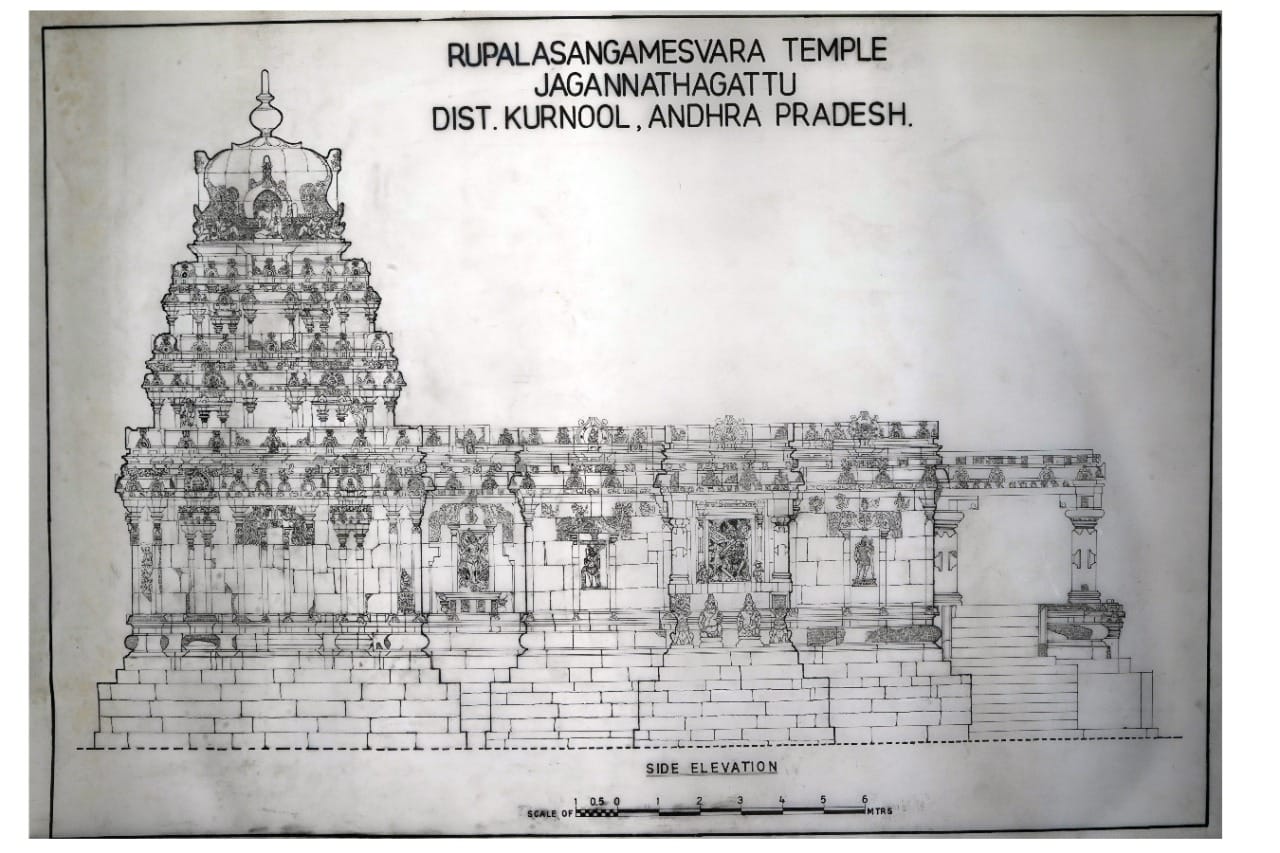

Since he began his career in 1977, he has illustrated the Bekal Fort in Kerala, helped put together a temple in Ratnagiri in Madhya Pradesh, brought to life through his drawings the structures of the Rashtrakuta dynasty in Karnataka, illustrated the paintings in Pandya caves in Tamil Nadu, and detailed the trenches dug at the Lalitagiri Buddhist Complex in Odisha. “Lalitagiri was the first time I visited an excavation site. It resembled a small mound,” he recollected.

Acquiring the skills of a draughtsman requires years of practice and for Palanivel it meant observing his supervisor at work when he first joined the ASI. “I admitted to him that I don’t know how to draw freehand. He asked me to accompany him on tour and learn,” he said. “I would stand next to him, after I had provided all the measurements of the site and watch him draw.”

Though he sits behind a desk now, his younger days were defined by adventure — hanging off temple structures, sometimes 200 feet above the ground. “At the time, I had to visit areas with no scaffolding and make my own rope ladders,” he said.

Palanivel vividly remembers the time he illustrated Puri’s Jagannath Temple in the early 1980s. “I would hold on to those ropes, rappel across the side of the temple wearing a shoulder bag, holding a pencil, a sheet of paper, and measure everything before climbing down to work on the drawing,” he said. “Back then, I was a young man.”