New Delhi: The name is Samarvir. Dr Samarvir. That’s how the 11-year-old boy from Karol Bagh introduces himself. He will become a doctor, marry a doctor, and keep alive the Sabharwal family’s 104-year-old doctor legacy.

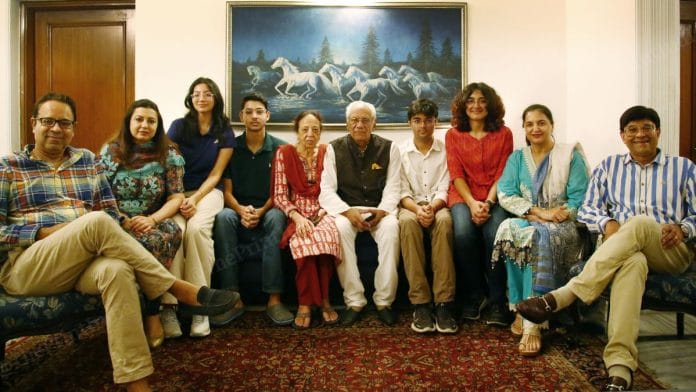

For five generations, every member of the family—more than 150 people—has been a doctor. Aunts, uncles, wives, husbands, grandparents, sons and daughters are all obstetrician-gynaecologists, radiologists, surgeons, orthopaedists, urologists, paediatricians, and general physicians. Today, the Sabharwals of Delhi have five hospitals in Karol Bagh, Ashram, and Vasant Vihar where different branches of the family live. It’s a profession they are extremely proud of.

As children, they grew up in hospital corridors and labs. They completed their homework in surgery rooms while witnessing an operation. One family member even refused to study history because it was not related to medicine. But the continuous line of doctors is breaking with the youngest and sixth generation. Unlike Samarvir who is convinced of his calling in life, a few of his older cousins are flexing their independence. They want to be writers, cricketers, engineers.

“We wish our children on their birthdays by telling them that they should become doctors when they grow up and keep the family legacy going,” said Dr Sudarshan Sabharwal, 84, the family matriarch. The retired gynaecologist who lives with her husband, a former laparoscopic surgeon, in Ashram, is not above running the gamut of emotions from love to guilt to convince her school and college-going grandchildren to take up the profession.

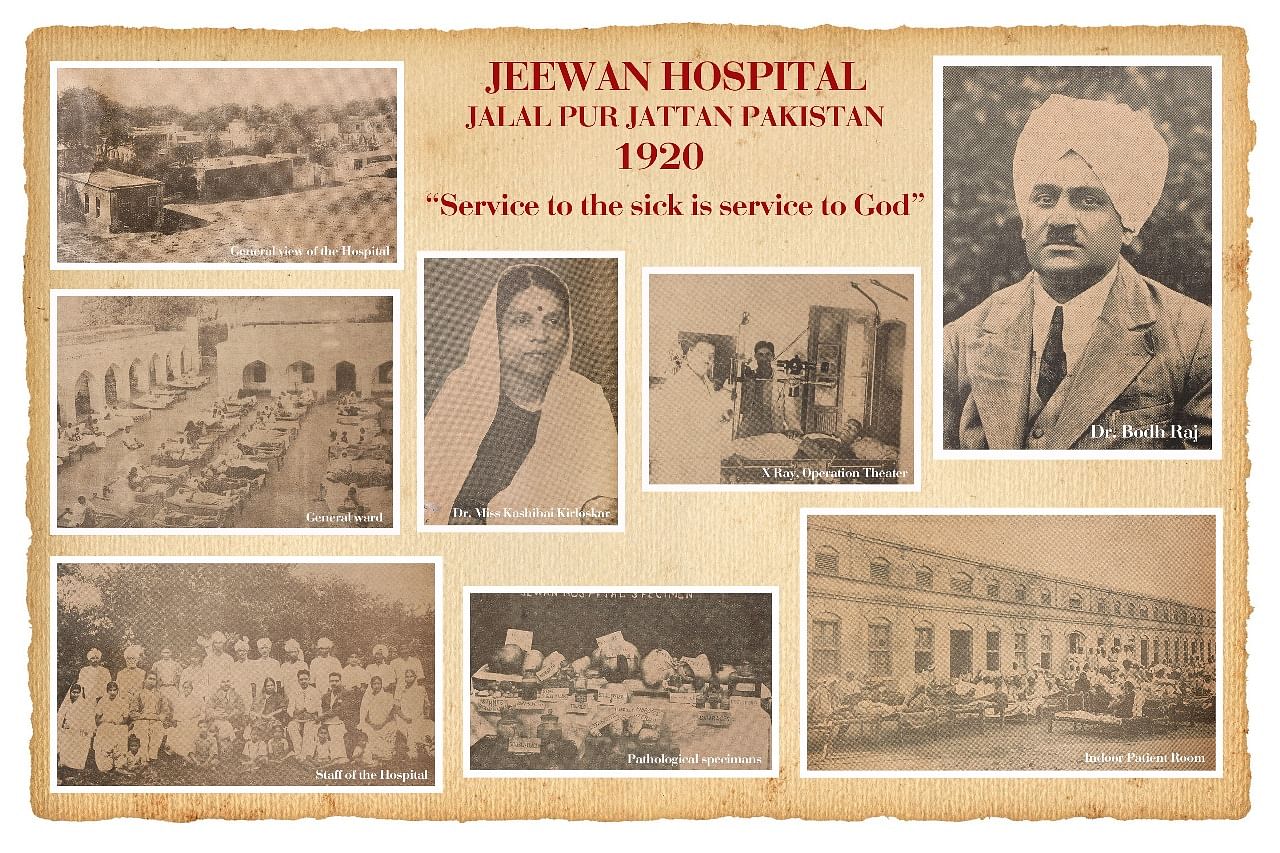

This doctor dynasty was built on the dreams of Lahore station master Lala Jeevanmal in the 1900s who wanted his four sons to be doctors. In 1920, the family got its first doctor and the tagline ‘Service to Sick is Service to God’. According to family lore, Jeevanmal always wished for his future generations to serve the community as doctors.

“Carrying forward our family’s legacy never felt like a burden to us. This profession and service to society is our first priority,” said Sudarshan’s nephew, Dr Ankush Sabharwal, 43.

Jeevanmal’s instructions weren’t just for the children, but also for their future spouses. In this family, spouses are matched not by kundalis, but by their profession.

“Whenever our children enter medical school, we always tell them that they can only date and marry a doctor,” said Sudarshan.

A family of healers

Dinner table conversations at the Sabharwal households revolve around their profession and patients. These days, it’s about the NEET-UG paper leak and student protests.

“NEET is already one the toughest exams, which needs years of preparation. Such incidents affect the confidence of students and [undermine] their years of hard work. The situation needs proper investigation. The government should also listen to what students have to say,” said Ankush, who got his MBBS degree from Government Medical College, Amritsar. Other members of the family nod in agreement.

We wish our children on their birthdays by telling them that they should become doctors when they grow up and keep the family legacy going – Dr Sudarshan Sabharwal, 84

With everyone in the same profession, conversations are easy as the family discusses patients, procedures and protocols. An emergency call from the hospital causing a family member to leave for work suddenly rarely disturbs the ebb and flow of life at home.

“Sometimes we run directly from the kitchen whenever we get any emergency call and because we don’t have to travel [since the family lives close to the hospital], it makes the pressure bearable,” said Dr Glossy (42), Ankush’s wife and the first radiologist among the Sabharwals. She, too, finds it easy to manage work-life balance because of the family dynamics.

“You don’t have to explain such emergencies because they [the family] know the profession demands a lot of your time,” she added.

Glossy slid into the family with ease—they welcomed her with open arms. She’s a doctor after all. But adjusting to seeing her in-laws in the more formal setting of a hospital took time.

“They are mummy-papa at home. But at work, I call them doctor,” said Glossy, who works at the family-owned Jeewan Mala Hospital in Karol Bagh.

“Even now, I sometimes call them mummy-papa at the hospital,” she added.

It can be disconcerting to see the same family members in an operating room or office when you also see them in an informal setting at home. Another daughter-in-law in the extended family, gynaecologist Dr Shivani who works at the same hospital, agreed. She teams up with her mother-in-law Dr Malvika for labour room emergencies.

“She’s two different people in the hospital and at home. She’s a very strict doctor and doesn’t like any mistakes when it comes to patient care. But outside the hospital, she is different, very understanding and helpful,” said Shivani, 43, as she adjusts her mother-in-law’s hair for a photo.

The rule of marrying only doctors was once broken when Sunal Sabharwal, 60, married Shakti, a student of biology. “After marrying into the family, she got fed up with the question, ‘Why is she not a doctor?’, “recalled one family member, adding that Shakti Sabharwal, 59, is now a doctor in America.

Also read: Distrust of Indian doctors isn’t new. Class-caste bias always ruled medical profession

The rebels

Not everyone is as accommodating as Shakti. Many among the sixth generation of Sabharwals are questioning the family’s obsession with the profession.

Diya Sabharwal, 21, managed to withstand all the emotional blackmail to pursue a double degree at Stanford University in California in English and computer science. She’s written for the Los Angeles Times and is a regular contributor to The Stanford Daily as well.

“Medicine is a beautiful field, but I’ve always known in my heart that it is not for me. While it can be very creative, the process of becoming a doctor itself is very laborious,” said Diya over WhatsApp. She’s completing her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in a combined five-year programme.

“I’m pursuing a career as an engineer and a writer. I’m particularly excited by the world of product design,” said Diya, who published a children’s book, A Not So Silent Night, when she was in the ninth grade in 2018.

Today, her family has accepted her decision, but it took years of pushback.

It takes fortitude to resist this kind of pressure, which comes both from within and outside. Teachers and hospital staff automatically expect young Sabharwal charges to become doctors.

“As soon as people heard our surname in school, they used to tell us that we would become doctors,” declared general and laparoscopic surgeon and fourth-generation doctor Vinay Sabharwal, 72.

Medicine is a beautiful field, but I’ve always known in my heart that it is not for me. While it can be very creative, the process of becoming a doctor itself is very laborious,” – Diya Sabharwal, 21

In Diya’s case, there were arguments and fights and she cried for days to convince her family.

“Becoming a doctor is definitely seen as a rite of passage. My parents really wanted me to be one,” she said. She grew up living on the second floor of Jeewan Hospital near Ashram.

“Staff would call me Dr Diya.” She even enrolled at the Akash Institute for NEET preparation when she was in the 10th grade. “I was almost convinced to give it a shot but at the end of the day, I felt it was draining my time and energy from the things I loved to do— creating and building new things was something I’m best at,” she said.

Unlike Diya, her cricket-crazy cousin Aryan, 16, has decided to study medicine after he completes 12th grade next year. He’s already started preparing for the NEET at home.

“Dadi [grandma] keeps forcing me and she keeps reminding me about the family legacy and how noble it is to treat people and help them,” said Aryan, pointing toward his grandmother with a smile.

But he’s still not sure whether he will actually see it through. His older sister Serena is already in medical school at the University of Central Lancashire in the United Kingdom.

Fortunately, his parents have come to accept that not all their children will become doctors.

“The new generation is always free to choose whatever they want to do. It’s good that they don’t face family pressure like the previous generation. Some are choosing medicine and some are not,” said Aryan’s mother, Dr Sheetal Sabharwal, a gynaecologist.

Also read:

Generational patients

The Sabharwal doctor dynasty started with Lala Jeevanmal Sabharwal, a station master in Lahore. According to the family, he was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s speech on how the future of India would rest on the quality of its education and healthcare.

At that moment, Jeevanmal decided he would build a hospital. He transferred his dreams and ambitions to his four sons, Bodhraj, Trilok Nath, Rajendra Nath, and Mahendra Nath.

In 1920, the family got their first doctor – Dr Bodhraj. And Lala Jeevanmal fulfilled his dream of establishing a hospital— in the Jalalpur city of Pakistan. During Partition, they fled Lahore, moved to Delhi, and started setting up hospitals again. By then, all of Jeevanmal’s sons had become doctors.

Every member of the Sabharwal family knows this story by heart—even those who want to resist this call of duty.

“My great-great-great-grandfather (Dr Bodhraj) treated his patients as family members. He always made sure to feed the people who came from far away and then started the medical treatment,” recalled Ankush.

Dr Bodhraj has been lionised in the family lore.

“He was not only a very good human being and doctor but a fighter and rebel as well. He refused the British government’s order to just treat the British and fought against the decision,” added Ankush.

Today, sepia photos of the Jalalpur hospital, Dr Bodhraj and his brothers line the walls of all five hospitals.

It’s not uncommon to see patients passing through the lobby and acknowledge the photos. These are ‘generational patients’ whose parents and grandparents too consulted the Sabharwals.

They are part of the Jeewan legacy as well. Bhavna Minocha’s great-great-great-grandmother was the first person from their family to visit the Jeewan Mala Hospital in Karol Bagh for an eye checkup.

“We have never been to any other hospital. I was born in the Jeewan Mala hospital and I gave birth to both my children here,” said Minocha (58). She won’t have it any other way.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)