New Delhi: As the festival of lights draws near, so does the gloomy haze of pollution in the national capital region (NCR). With air quality expected to plunge to “very poor” levels ahead of Diwali, the Union government’s Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM) launched the second stage of its Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) Wednesday.

However, scientists warn that the real challenge will come after Diwali on 24 October, when the combined effects of fireworks, weather, and other factors may yet again lead to a toxic smog over the city.

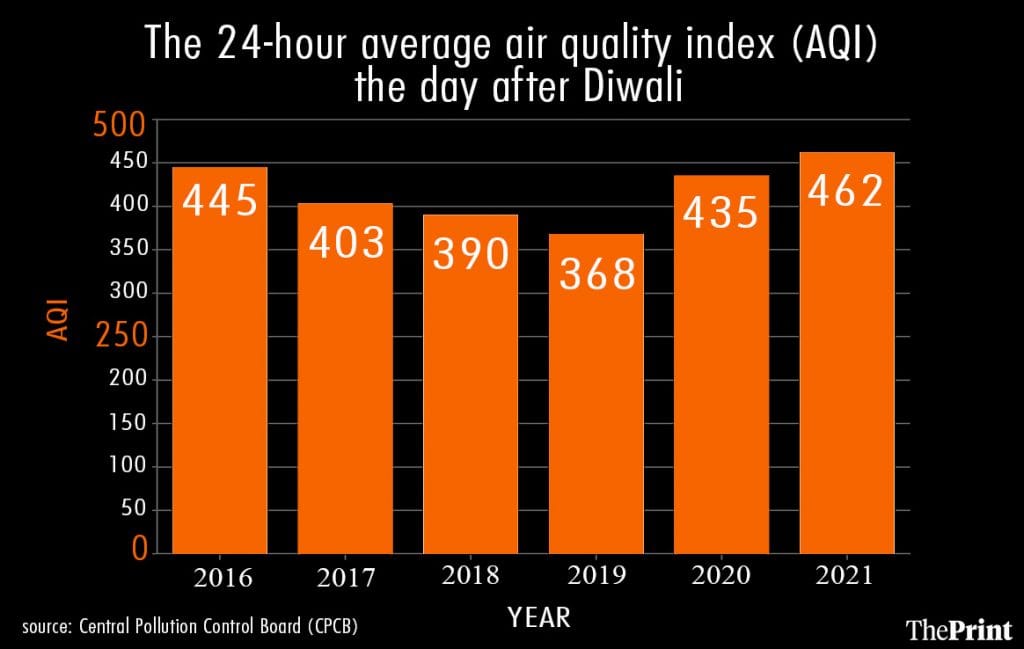

Even Diwali falling in a ‘warmer’ month may not save the day. Earlier this month, scientists with the System of Air Quality and Weather Forecasting and Research (SAFAR)-Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM) reportedly said pollution levels may be lower because this year’s Diwali falls in October rather than November, when cooler air traps more pollutants. But data shows this has not made much of a difference in earlier years.

“The level of pollution around Diwali will depend on two factors — emissions from firecrackers and vehicles, and the meteorological conditions around that time,” said Dr Vijay Kumar Soni, head of the environment monitoring and research centre at the India Meteorological Department (IMD).

He told ThePrint that air pollution in the national capital has always ranged from ‘very poor’ to ‘severe’ after Diwali, regardless of the month it falls in. While in 2020 rains later helped reduce pollution levels starkly, chances of that happening this year are small, he added.

In 2017, when Diwali was celebrated on 19 October, the 24-hour average air quality index (AQI) the next day was 403 (severe), data from the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) shows. In 2019, when Diwali fell on 27 October, air pollution levels reached 368 (very poor). In 2020, air pollution the day after Diwali (November 14) was recorded at 435 (severe), and 462 (severe) in 2021, when the festival fell on 4 November.

If there is any good news, it is that the effects from stubble burning at farms in Punjab might be less pronounced this year. “This time we will be experiencing winds blowing from the eastern side of the country, which will restrict the contribution of stubble burning towards pollution,” Soni said.

Also read: Delhi govt enforces 15-step action plan to tackle air pollution ahead of winter

A toxic season

The Delhi government last month put in force a “complete ban” against the manufacture, storage, sale, and use of firecrackers until 1 January 2023. However, bans in previous years have had only limited success in Delhi, with many people flouting rules. Underhanded sales continue even now. This week alone, for instance, the Delhi Police seized over 2,000 kg of firecrackers in four different operations.

Firecrackers, of course, are not the only issue. The onset of winter, coupled with biomass burning and crop residue burning in neighbouring states are among the major factors responsible for poor air quality every festive season in Delhi.

“Meteorology can change its face within 12 hours, so we just have to wait and see what the air quality will be like after Diwali. We can continue to expect to see all the combustion sources in the contributions pie — transport, power plants, cooking, heating, garbage burning, road and construction dust, and any remnants of the Diwali fireworks,” said Dr Sarath Guttikunda, founder and director at Urban Emissions, a platform that analyses air pollution.

‘Fewer farm fires this year’

Diwali normally coincides with the paddy crop residue burning season, which typically lasts from 15 October to 15 November. It is also the biggest contributing factor to air pollution in the national capital during this time period.

According to data with the Indian Agricultural Research Institute, satellites have detected a total of 3,491 instances of stubble burning between 15 September and 19 October, a majority of which were recorded in Punjab, north of Delhi.

Heavy rain on 3 October, at a time when the monsoon should have withdrawn, could push the peak of stubble burning — usually crossed by the first week of November — by a week to 10 days, said experts.

“I expect instances of stubble burning to decrease this year. The numbers will go up through the stubble burning season, but our expectation is that there will be fewer fires compared to last year, and substantially fewer fires compared to 2020,” V K Sehgal, principal scientist at the Consortium for Research on Agroecosystem Monitoring and Modeling from Space (CREAMS) of the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), told ThePrint.

Farm fires in Punjab had reached a count of 8,509 on 19 October in 2020, but the number has dropped to 2,625 this year on the same date. In 2021, fires were marginally higher, at 2,942.

Sehgal said he believed this reduction was “to a certain extent ” because of the delay in monsoon withdrawal, but also because “the state and central governments were working proactively to address the problem” by providing alternatives to burning.

Experts have long said the underlying problem is the cultivation of paddy in a water-scarce region, when the time gap between the harvesting of the Kharif crop and sowing of the Rabi crop is too narrow.

IARI’s Sehgal said that the area of paddy cultivation in Punjab and Haryana increased slightly in Punjab this year, according to remote sensing estimates. It increased to 3.026 million hectares from 2.968 million hectares in 2021.

Beyond just Diwali

Air pollution in the national capital region and the Indo-Gangetic plain is driven by factors beyond just firecrackers and crop residue burning, whose effects wear off by mid-November.

A study by the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Delhi showed that in the days after Diwali, it was biomass burning — setting fire to wood or other substances for cooking and warmth — that worsened Delhi’s air. The effects of fireworks wore out after 12 hours.

A 2021 study by the Council on Environment, Energy and Water (CEEW) also found that transport, dust, and cooking and heating were the biggest contributors to air pollution 15 November onwards, till the end of the winter season.

“Vehicular pollution is a big source of pollution in Delhi overall. Around Diwali, if the vehicular movement increases, that can cause more emissions. The scientific community has now understood that pollution is a shared problem, so the measures taken by the Delhi government will not be enough, what happens in the NCR region is also a causal factor,” said Anumita Roy Chowdhury, executive director of research and advocacy at the Delhi-based non-profit Centre for Science and Environment.

Deploying the Graded Response Action Plan using “forecasted source contributions and forecasts of pollution peaks” can help manage air pollution better, according to the CEEW.

The CAQM has started to do this, but it’s still too early to evaluate the effectiveness of the CAQM’s policies, said Tanushree Ganguly, one of the authors of the CEEW study.

“We found that forecasts could follow the trend of air pollution, but consistently under-predicted the absolute concentration levels of pollution. There’s room for improvement, particularly in our ability to attribute air pollution to various sources,” she said.

According to Urban Emissions’ Guttikunda, forecast models of pollution have some limitations.

“Forecast models depend on baseline emission inventory — for both the intensity of the emissions and spatial/temporal representation of these emissions. Oftentimes, both the activities are supported by some known fields of information, like technology in use, layers of geographic data, activity levels, fuel consumption patterns, etc., but there are still gaps in our understanding of estimating and representing these emissions,” he said.

The “challenges multiply”, Guttikunda added, when trying to comprehensively cover not just known sources of pollution but also accounting for unknown sources.

“We try our best to minimise these uncertainties with notes from field experiments, surveys, and other observations whenever they are available,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also read: You thought only winter meant bad air in Delhi? Govt data tells a different, worrying story