New Delhi: The central government, in a bid to reduce the country’s import dependence, is taking steps to ensure that starting 2026, solar projects in India will only be able to use solar cells made by ‘approved’ manufacturers. But a number of industry participants say India’s cell manufacturing capacity, well below requirements, will not likely reach the required level by 2026 with its current pace of growth.

The Centre on 11 December 2024 announced that the approved list of models and manufacturers (ALMM) for solar projects in the country will soon be expanded to include solar cells too. Once it comes into force in June 2026, ALMM ‘list 2’ will mean that any state or central governments solar projects, as well as open-source and net-metering projects, will need to use solar cells made by Indian manufacturers whose names are in the list.

In April 2024, it had enforced ALMM ‘list 1’ that mandated the same for solar modules.

The scheme is meant to reduce the import dependence on China for India’s solar sector, arguably the fastest-growing renewable energy sector in the world, with a total of 97.86 GW installed capacity as of December 2024. However, with a year and a half left to the imposition of ALMM ‘list 2’, and a mere 8.1 GW of solar cell-making capacity in India as of December 2024, some in the industry are of the opinion that the order is pre-emptive.

“We currently need at least 20 GW of cells annually in India given our solar demand—our internal production right now is barely 10 GW,” Vinod Gupta, chief investment officer of SAEL (Sukhbir Agro Energy Limited) Power, one of India’s top 10 solar module manufacturers, told ThePrint. “There are projects in the pipeline but cell manufacturing is highly technical and complicated, not everyone can do it.”

Others, however, are positive that by the time the order comes into force, India will have enough, even surplus domestic solar cell capacity.

Three different analyst firms—Kotak Securities, CRISIL (Credit Rating Information Services of India Limited), and Mercom India—predict different levels of capacity addition by 2026 based on current levels and future announcements by companies.

CRISIL is the most conservative at estimating 43-45 GW solar cell capacity by 2026, while Kotak Securities puts it at 54 GW, and Mercom India’s State of Solar Manufacturing in India 2024 report says that India will see 75 GW of domestic solar cell capacity by 2026.

However, these numbers and projections come with a caveat—commissioning the announced solar cell projects will be crucial.

Also Read: SECI says power producers like Adani & Azure have option to cut tariffs if nobody’s buying

Solar cell manufacturing: Closed circle

Solar cells are essentially the second rung in the process of making a solar power plant: any plant/project is made up of multiple rows of solar panels, called solar modules.

These modules, in turn, are made up of rows of individual solar cells largely manufactured using thin silicon wafers.

In India currently, most solar manufacturing is done to make solar modules.

To incentivise domestic production, the central government released an ALMM ‘list 1’ for solar modules in 2019, which was implemented first in 2021 and again in April 2024.

The ALMM ‘list 1’ dictates that government solar projects should only use domestic solar modules. Once it comes into force in 2026, ALMM ‘list 2’ will dictate that these solar modules should in turn use domestically made solar cells.

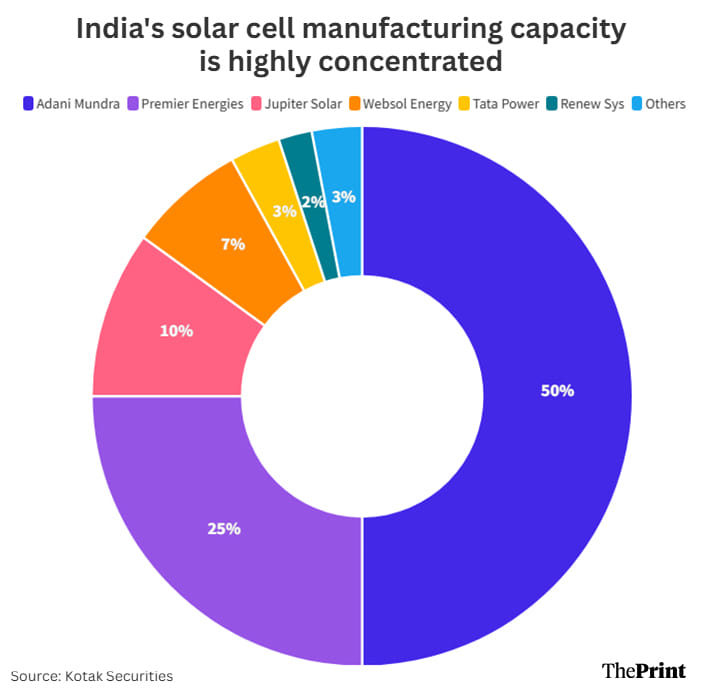

But there is a huge gap in production. As of December 2024, there is less than 10 GW of solar cell production in India, and Adani’s Mundra plant produces half of this capacity.

Put simply, six companies manufacture nearly all of India’s solar cells—Adani, Premier Energies, Tata, Websol, Renew Sys, and Jupiter.

Solar module manufacturing, on the other hand, was at 77 GW in June 2024 and is predicted to increase to 150 GW by 2026, dominated by many of the same players like Adani, Tata and Premier, besides Waaree, and Reliance.

Right now, according to Kotak Securities’ December 2024 report, domestic solar cells cater to around 20-30 percent of the domestic demand. With the imposition of ALMM ‘list 2’, they will need to cater to 90 percent of the demand by June 2026. To do this, there needs to be immediate commissioning of the announced cell manufacturing projects by Waaree Energies, Reliance, and ReNew Power. They are confident they can do it.

“Not just this year, I can say that in the next couple of months, India’s solar cell production will comfortably reach at least 20 GW,” Amit Paithankar, CEO of Waaree Energies, whose 5.4 GW solar cell manufacturing plant began trial production this month, told ThePrint.

Backward integration & higher costs

CRISIL Market Intelligence and Analytics in their 18 December 2024 report said that the ALMM ‘list 2’ could “pose significant challenges” to companies that don’t manufacture their own cells, since they will need to rely on the existing few cell manufacturers for procurement. One of the main reasons for this challenge is that currently, imported cells from China and other countries are significantly cheaper than cell manufacturing in India.

“Also, the prices of Indian solar cells today are 1.5 to two times more than alternatives from China even after basic customs duty. High prices can drive up the capital cost of solar power projects,” said Sehul Bhatt, director-research at CRISIL Market Intelligence and Analytics, in the report.

For India’s solar module-making companies that do not have backward integration—that is, they do not manufacture their own cells—depending on the existing players could be a drawback. If they are unable to procure from domestic cell manufacturers, they run the risk of being delisted from ALMM ‘list 1’, thus being unable to supply modules to any government projects. Also, high costs of solar cells would be detrimental for consumers, too, since they will lead to an increase in tariff costs, or could potentially put a dent in India’s renewable energy expansion plans of 500 GW by 2030.

The ALMM lists and other government initiatives like production-linked incentives (PLIs) are meant to increase investment in solar manufacturing so that Indian solar project developers do not rely on imports. However, as ThePrint reported earlier, despite increasing domestic solar module production, Indian developers still imported modules and cells from abroad while Indian modules were largely exported to the US.

Domestic module manufacturers like Adani, Waaree, and Vikram Solar exported 50-70 percent of their total module production even in FY2024.

While SAEL Power too has plans to set up its own cell manufacturing unit in the next two years, Gupta pointed out that there is a difference in setting up module manufacturing plants as opposed to cell manufacturing. “Any new companies getting into cell and module manufacturing will have to think of long-term success, not just initial requirements.”

“It is capital and technology-intensive, and with cell production technology changing so rapidly around the world, it might not make sense to own a plant after four years,” he said.

CRISIL’s Sehul Bhatt agreed. “The main challenge in the coming years for solar cell manufacturers will be to keep up or adapt to technological advances so as to avoid obsolescence,” he told ThePrint.

Gupta also cautioned that the establishment of large-scale solar cell manufacturing plants will require a skilled workforce, which is currently not available in India. Any focus on expanding manufacturing will need an equally important focus on upskilling the workforce to work in such specific sectors, said Gupta. However, Waaree’s Paithankar said that the ALMM ‘list 2’ will spur cell manufacturing just like ‘list 1’ did for module manufacturing.

“We went from just 20-25 GW solar module capacity in 2021 to now almost 65 GW of ALMM module capacity—that isn’t a small feat,” said Paithankar. “I am positive that the solar cell industry too will see a similar shift.”

One of the ways Waaree decided to raise money for solar cell manufacturing was through an IPO listing in October 2024. Following the trend of renewable energy companies like Premier Energies, Waaree’s IPO also made a stellar debut on the National Stock Exchange (NSE) with a high premium price. In the coming years, other renewable energy companies like SAEL Power too are planning to go the IPO route.

Import-export reliance

Whether shifting to domestic solar cells will reduce India’s reliance on solar imports from China, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand is another question altogether.

A report by the Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI) in October 2024 said that India, like the US and European Union (EU), is heavily reliant on China for its solar industry currently. This is evident in solar cells and modules imports to India over the past five years.

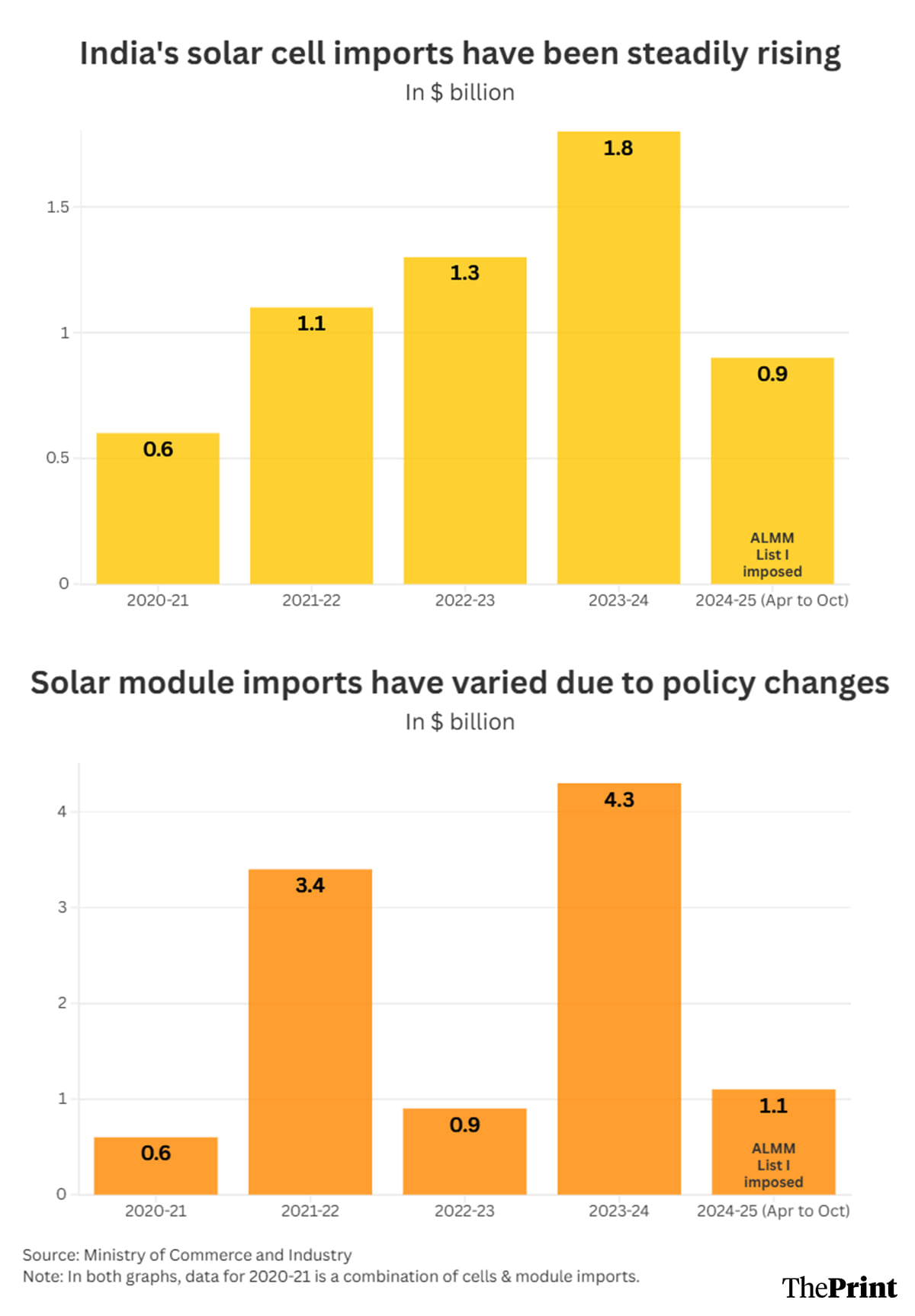

India’s imports of solar cells has steadily increased since 2021, with a dip only after 2024 April, when the ALMM ‘list 1’ for solar modules came into force. However, even then, imports between April to October 2024 were higher than all imports in FY 2020-21.

Data shows that India’s imports of solar modules jumped rapidly from 2020 to 2022, then fell massively in 2022-23 after the Centre introduced a 40-percent customs duty on solar imports. Then, in 2023-24, as China experienced a price crash in solar panels and India went on a spree of solar projects before ALMM came into force, imports increased again.

Then, in April 2024, when the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy enforced ALMM ‘list 1’ again, they came down. But India still imported $1 billion worth of solar modules between April to October in 2024.

All roads still lead to China

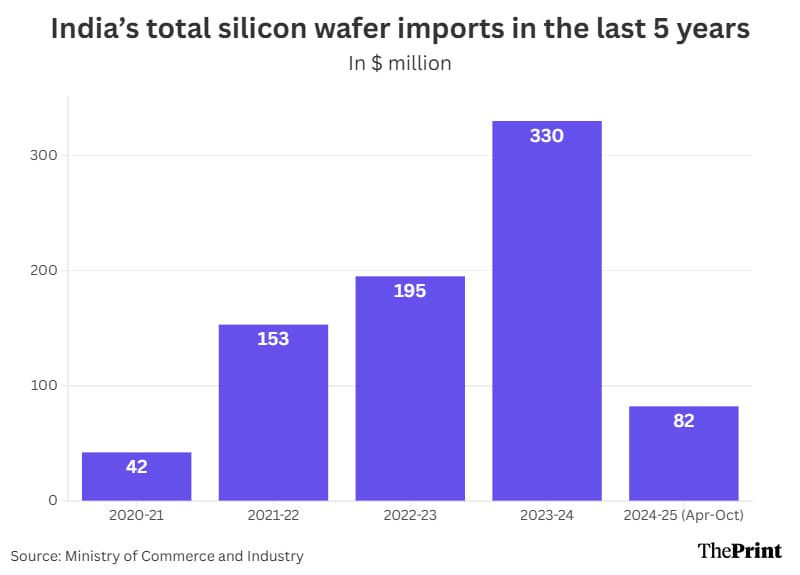

What is important to note is that even if India produces solar cells domestically, it will still rely on China and other countries to import the silicon wafers, raw materials, and equipment used for making solar cells and modules. Paithankar told ThePrint that even Waaree’s solar cell facility will use imported wafers and equipment since India’s own production of these is minimal, with most of the world dependent on China.

Also, with reports of China bringing in export curbs on critical equipment for solar production, it will be difficult for new cell manufacturing units to flourish in India.

India’s silicon wafer imports show an increasing trend from 2020 onwards. While there is a dip in 2024-25, according to Neshwin Rodrigues, an analyst at Ember, this is because it accounts for only 7 months’ data (April-October), and not the remaining five months.

“With local production for cells taking off, import dependency will continue for everything from polysilicon to wafers—in fact, the import of wafers will increase in the next few years,” remarked Bhatt.

“To cut down on imports, India needs to produce solar cells starting from silica refining, which involves costly and energy-intensive polysilicon production and requires advanced technology,” suggested the GTRI report. It also said that currently, there is no Indian company that produces solar cells from scratch using silica sand to make wafers. Adani Solar became India’s first-ever ingot producer in April 2024, using imported polysilicon.

The GTRI report cautioned that in case India’s solar production capacity does not pick up, the import reliance could be to the scale of $30 billion annually by 2030.

(Edited by Radifah Kabir)

Also Read: India slams the brakes on surge in Chinese solar imports, but domestic industry still needs them