New Delhi: Farmers in Punjab and Haryana shifted stubble burning timings from early afternoon to evening hours, likely to avoid detection by polar satellites, according to a new ISRO study, which says such a move would have led to an underestimation of farm fire counts.

The study by scientists from Indian Space Research Organisation’s Space Application Centre (SAC) challenges official claims of a sharp decline in farm fires this year. Instead of the practice being shed, stubble burning was simply carried out later, to avoid being mapped by NASA’s polar satellites MODIS and VIIRS, it says.

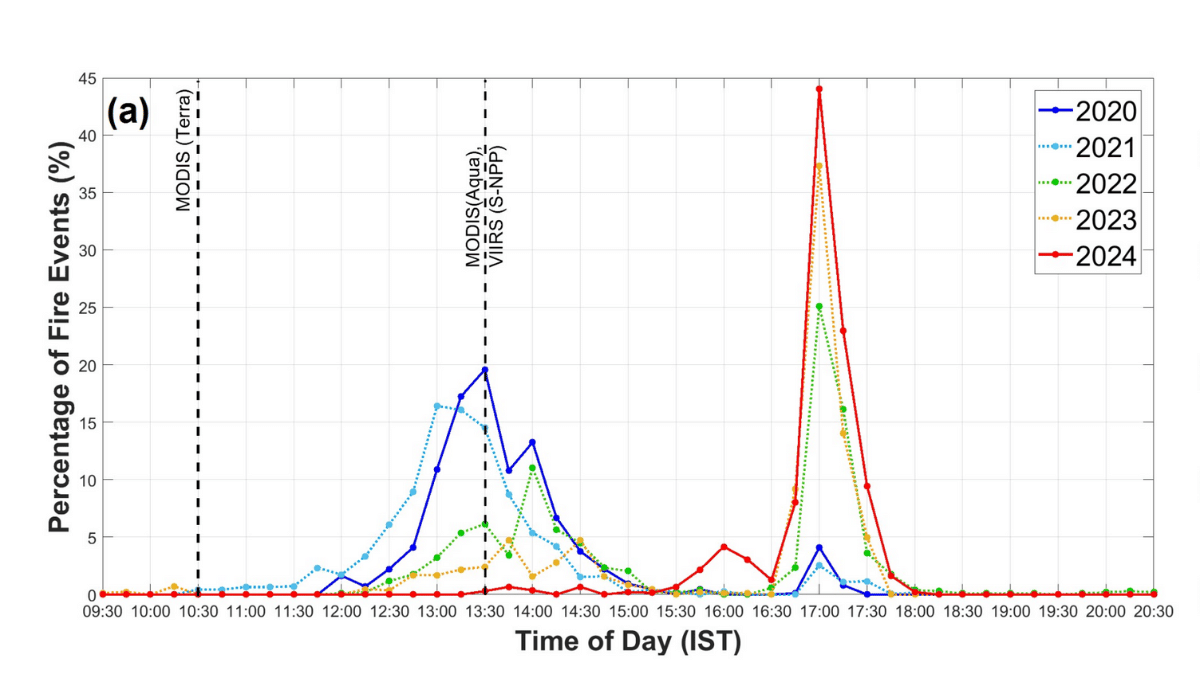

“We observe a gradual temporal shift between 2021 and 2024, with peak fire activity occurring around 17:00 IST in 2024… At the same time, the window of fire activity narrowed substantially, suggesting an informed adjustment by farmers to avoid detection by polar-orbiting sensors,” the study, published in Current Science on 24 November, said.

The findings contradict the Commission for Air Quality Management’s (CAQM) statement this Monday that farm fires in Punjab and Haryana dropped nearly 90 percent between 2020 and 2024. This decline, the commission said, was driven by “state action plans, deployment of crop-residue management machinery, and strict enforcement measures”.

Every year, farm fires typically spike with the onset of winter as farmers set alight paddy stubble to clear their fields for the next round of sowing. Coupled with cold weather conditions, pollutants from stubble burning and other sources envelop large parts of northwest India under toxic haze that lasts weeks, if not months.

As farm fires peak between mid-September and mid-November, governments and CAQM deploy various measures such as penalties and construction bans to cut down pollution. State governments, however, have struggled to completely snub out farm fires, which are considered the fastest and most cost-efficient way to ready fields for the next crop.

How ISRO’s study differs

ISRO researchers used data of fire counts from the European Space Agency’s geostationary MSG satellites, which remain in a fixed position and move with Earth’s rotation, unlike the NASA satellites that orbit the planet and pass over a single location once daily.

Theoretically, if a fire is not raging at the time a polar satellite is crossing over a region, it won’t be counted at all. The same is not possible with geostationary satellites, which capture imagery throughout the day.

Analysis of MSG satellite data from 2020 to 2024 revealed a clear pattern: while stubble fires in Punjab and Haryana began around 12 pm and continued till 2 pm in 2020 to 2021, from 2022 onwards, they peaked between 4:30 pm and 6:00 pm—well after the NASA satellites crossed the region.

CAQM, in August 2021, standardised its fire detection methodology, and decided to use MODIS and VIIRS data to count farm fires from Punjab, Haryana, UP, Rajasthan and Delhi-NCR. The decision was taken after recommendations from several experts and agencies, including ISRO.

The study’s findings align with research by Hiren Jethva, a senior aerosol remote sensing scientist with NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, who has been flagging potential underestimation in farm fire counts since last year.

“Claims of ‘92% reduction’ in Punjab’s crop fires are false/misleading—they rely on NASA–NOAA satellites that miss most late-afternoon fires,” Jethva reiterated in a post on X Monday.

Jethva’s analysis using aerosol optical depth—a method that measures pollution based on how much sunlight is scattered by suspended particles—showed that October 2025 recorded the third-highest pollution level in the last 15 years. Record-high pollution levels do not point to the decline in farm fires, he suggested.

The ISRO study pointed to this “critical gap” in monitoring farm fires and recommended that authorities use a combination of polar-orbiting satellites like MODIS and geostationary satellites like MSG to get a “complete picture” of stubble burning in northwest India.

“Underestimation of active fire events during October–November in Punjab and Haryana can lead to a substantial underestimation of carbon emissions,” the study said.

The ISRO study acknowledged that while MSG satellite data was not of very high resolution, it could still detect fire activity and the changes in peak timings.

ThePrint has also previously documented how some farmers were purposely avoiding detection by changing fire timings.

Other experts Wednesday calling for transparent and reliable data.

“When such data and assessment tools are missing, major emission sources can go unnoticed in discussions and action plans, creating a false impression of progress or reduction,” said Sunil Dahiya, Founder and Lead Analyst of Envirocatalysts.

But not all researchers agree with this theory.

Ravindra Khaiwal, an expert on public and environmental health from the Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER) in Chandigarh, dismissed the claims last year.

“Claims that Punjab farmers evading fire detection by burning after 2 pm to avoid satellite detection is unsubstantiated. Over 95% of fires are detected in morning passes, not evening. The reduction in fire counts is likely due to improved enforcement & alternative practices,” he had written on X.

Delhi’s air quality this November remained largely ‘very poor’ and exceeded ‘severe’ levels. Between 10 and 18 November, stubble burning’s contribution to air pollution in the capital was almost 25 percent, according to an assessment by the Decision Support System (DSS), which is managed by the Ministry of Earth Sciences and IITM (Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology)-Pune. This data, too, depends on MODIS and VIIRS satellite counts.

CAQM members did not respond to requests for comment till Wednesday evening.

(Edited by Prerna Madan)

Also Read: A 40-year legal battle for clean air: Why Delhi breathes poison despite steadfast judicial crusade

This mindset is why countries like India do not live upto its potential. Rather than showing understanding and compassion people tend to shrug things under the carpet or shift blame to others. And this is not a bane of democracy. It is a degenerate example of chalta hai attitude. Nation building cannot progress with such a mindset.