New Delhi: Fifty years ago, when the critically acclaimed English singer-songwriter David Robert Jones, better known as David Bowie, released his sixth studio album ‘Aladdin Sane’, little did anyone know that the album cover would go on to become one of Bowie’s most “celebrated images”.

From his debut in 1967 until his death in 2016, Bowie remained at the centre of both acclaim and controversy, not only for his personal life, but also for his musical and artistic output every step of the way.

Bowie’s career and public image a year after the release of his breakthrough album, ‘The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars’ or ‘Ziggy Stardust’ (1972), were defined by the artwork for his sequel album, ‘Aladdin Sane’ released in 1973.

A continuation of Bowie’s signature glam rock style and groundbreaking production that defined ‘Ziggy Stardust’, ‘Aladdin Sane’ the 10-track album that runs at a little over 41 minutes was released to critical acclaim and heightened financial success for the 1973 Good Friday long weekend, propelling Bowie further into the stardom stratosphere.

Wordplay on both the centuries-old Arabic folk tale and the phrase “a lad insane”, it featured a new eponymous fictional character created by Bowie, who was also the central figure in the album’s artwork.

Overall, having sold more than 5 lakh copies in the US and topped the charts in the UK, its legacy puts ‘Aladdin Sane’ among Bowie’s highest-rated works as well as one of the most seminal works of the 1970s.

The magazine Rolling Stone also named it among four other Bowie albums in its 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list.

In his book, The Complete David Bowie, Nicholas Pegg reveals that the album went through multiple titles, including “A Lad Insane” and “Love Aladdin Vein”, but Bowie opted to drop the word “Vein” to avoid direct references to drugs.

Also Read: Netflix’s Treason stops short of an exercise in wasting everyone’s time

The album cover imagery

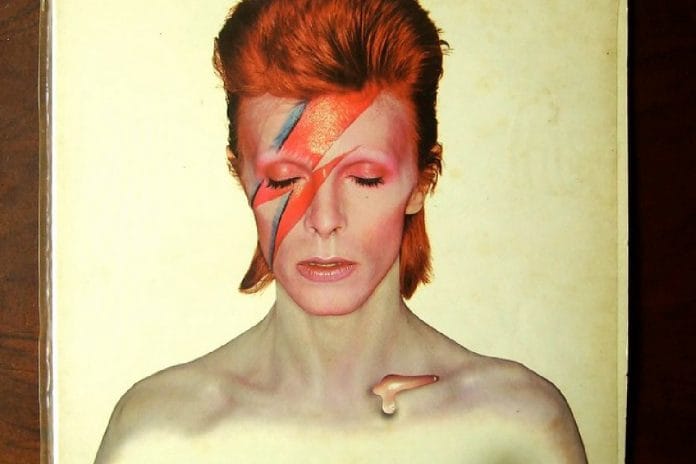

“The photoshoot for ‘Aladdin Sane’ was conducted by Brian Duffy, a prominent British photographer of the 1960s and 1970s, and resulted in “the most celebrated image of Bowie’s long career”, writes Pegg in the singer’s biography.

The image itself is of a topless close-up of Bowie’s head and shoulders. Bowie’s hair is a flaming red colour in this. His eyes are closed and his face sports a red and blue lightning bolt while a teardrop runs down his collarbone. The teardrop was added by Duffy in post-production.

“[Duffy] believed that the ‘flash’ design came from a ring once worn by Elvis Presley, but the image itself has wider implications: the elaborate makeup is a deliberate expression of the fractured, ‘split down the middle’ personality Bowie himself described,” Pegg writes.

According to biographer David Buckley’s Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story, ‘Aladdin Sane‘ represented a shift away from the previously established or ‘Ziggy Stardust’ character as Bowie was now writing from the position of already being famous and was reacting to a frustrating, financially unfavourable deal he had signed with a management firm.

The ‘Aladdin Sane’ character is, thus, meant to represent Bowie dealing to his newfound fame and spending a significant amount of time, or as Bowie himself puts it — “Ziggy goes to America”, as most of the writing process had taken place during his tour of the US to promote the release of ‘Ziggy Stardust’.

The image would make Bowie nearly synonymous with the fictional characters he created during his album promotion processes, not just during this period but also long after the 1970s, continuing to influence popular culture to this day.

But in an interview with the Rolling Stone magazine in 1987, Bowie revealed that his ‘Aladdin Sane’ character was meant to be ephemeral before “mutating” into one of his next albums, ‘Diamond Dogs’ in 1974.

Within that brief period of Aladdin Sane’s release, this ephemeral character’s imagery divided opinions among music writers, critics and fans, for whom analysing Bowie’s work meant looking at the full package — the music, the promotional artwork and the public personas.

Rolling Stone writer Ben Gerson characterised Bowie as being “airbrushed into androgyny” (i.e. possessing both masculine and feminine characteristics), with Bowie’s “program” in ‘Aladdin Sane’ involving “the elimination of gender differences”.

“The titles may change from album to album — from the superman, the homo superior, Ziggy, to Aladdin — but the vision, and Bowie’s rightful place in it, remain constant. The pun of the title, alternately vaunted and dismissive, plays on his own sense of discrepancy. Which way you read it depends upon whether you are viewing the present from the eyes of the past or the future,” Gerson added.

Another contemporary was The New York Times’ Henry Edwards, who in a similar vein to Gerson, described Bowie’s costumes as “the very definition of overwrought uni-sex fashion” and the ‘Aladdin Sane’ artwork as “the most cunning representation to date of this angel-faced, 25-year-old, English composer-performer as a disembodied spirit of the Space Age.”

“Bowie not only has an epicene air about him but also looks as if he had been plated with a chromium alloy… Bowie has been given a luminous new rouging and shellacking, and his tinted hair has been given the obligatory glinting touch-up,” Edwards added.

A prolific singer-songwriter buoyed by his meteoric rise, Bowie would go on to release 20 more studio albums in the decades following ‘Aladdin Sane’.

Aside from the discourse on the flashy artwork exterior, Bowie continued to receive critical acclaim for his records’ productions and compositions, culminating in Blackstar which was released on his 69th birthday, two days before his death in January 2016.

(Edited by Anumeha Saxena)

Also Read: Oscar-nominated Tár is a Cate Blanchett show from the get-go. She will thrill you, stun you