New Delhi: The Chinese economic miracle of high growth witnessed between 1978 and 2010 has come to an end with Beijing slowly transforming the fundamentals with which the economy operates, said Barry Naughton, an economist and expert on China.

“Young people are unemployed in China and not being absorbed by the economy. The Chinese economy is also facing a situation of mild-deflation (falling prices), even as its currency, the Renminbi Yuan, has depreciated, while the stock market has been doing terribly,” said Naughton, So Kwan Lok chair of Chinese international affairs at the University of California, San Diego.

Naughton was speaking at the 2024 Gargi and V.P. Dutt Memorial Lecture, organised by the Institute of Chinese Studies, New Delhi, at the India International Centre (IIC) on 3 April. ThePrint was a partner for the event.

Naughton’s lecture titled China’s Economic Slowdown: Structural, Cyclical and Systemic attempted to explain how the Chinese economy is undergoing restructuring, especially post the Covid-19 pandemic under President Xi Jinping.

“The complete absence of a [economic] recovery bounce after China’s Zero Covid strategies was surprising. It suggests that the setting of its macroeconomic policy is wrong. The aggregate demand of the economy is too weak when compared to the supply of the economy,” explained Naughton.

This, he asserted, has created a change in the perception of the Chinese economy both domestically and internationally. Some of the perceptual changes are “reasonable”, while others are “overstated”, especially in Washington D.C, Naughton pointed out.

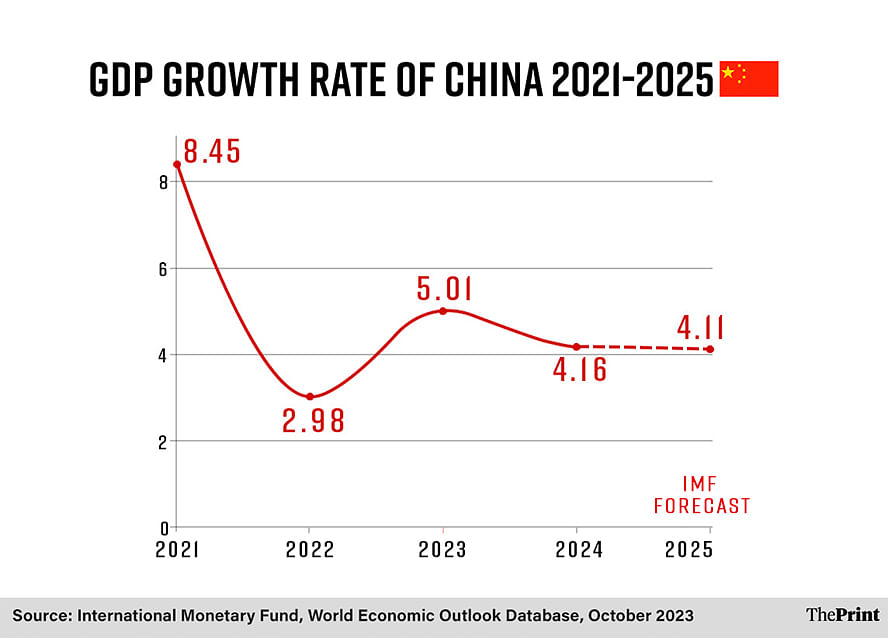

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Chinese economy grew by 8.45 percent in 2021, but the bounce dropped off in 2022 with only 2.989 percent growth as strict lockdown restrictions were placed on a myriad of Chinese cities, including one of the largest ever in the mainland in Shanghai from February 2022 to August 2022.

In 2023, China’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 5 percent, while it is expected to grow by around 4.1 percent in 2024 and 2025. In March 2024, the Chinese government set its own growth target of “around 5 percent”, according to local media reports.

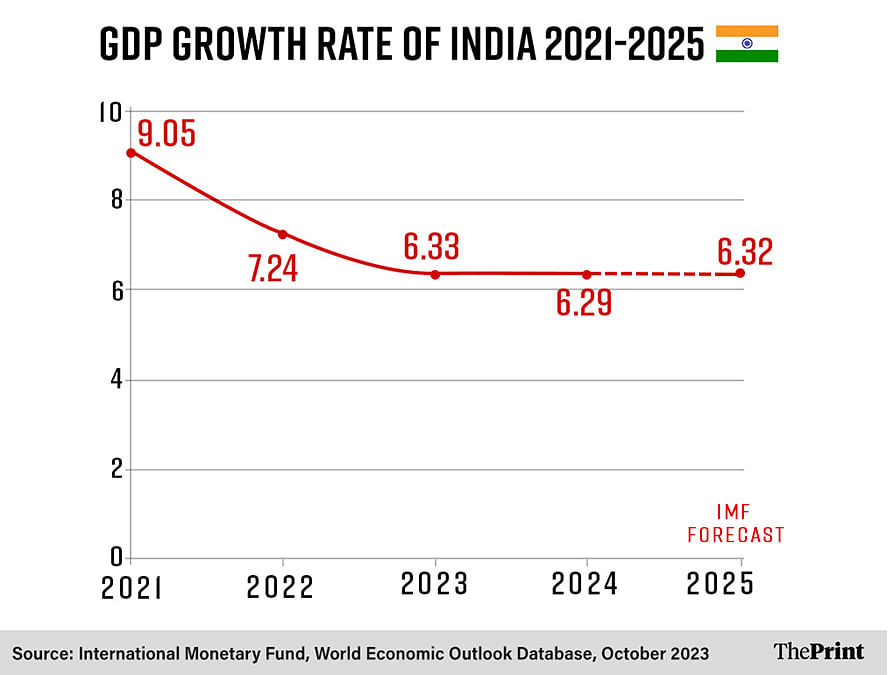

In comparison, India’s GDP grew by 9 percent in 2021, which dropped to 7.2 percent and 6.33 percent in 2022 and 2023, respectively, according to the IMF. The IMF forecasts the Indian economy to grow by 6.3 percent in 2024 and 2025.

There may be minor discrepancies between the IMF GDP forecast and the country’s own.

Also Read: Xi admits ‘headwinds’ staring down Chinese economy — slowdown, unemployment

China’s economic gamble

According to Naughton, the Chinese government is attempting an “economic gamble” to prevent its economy from hitting the “lost decades” of Japan.

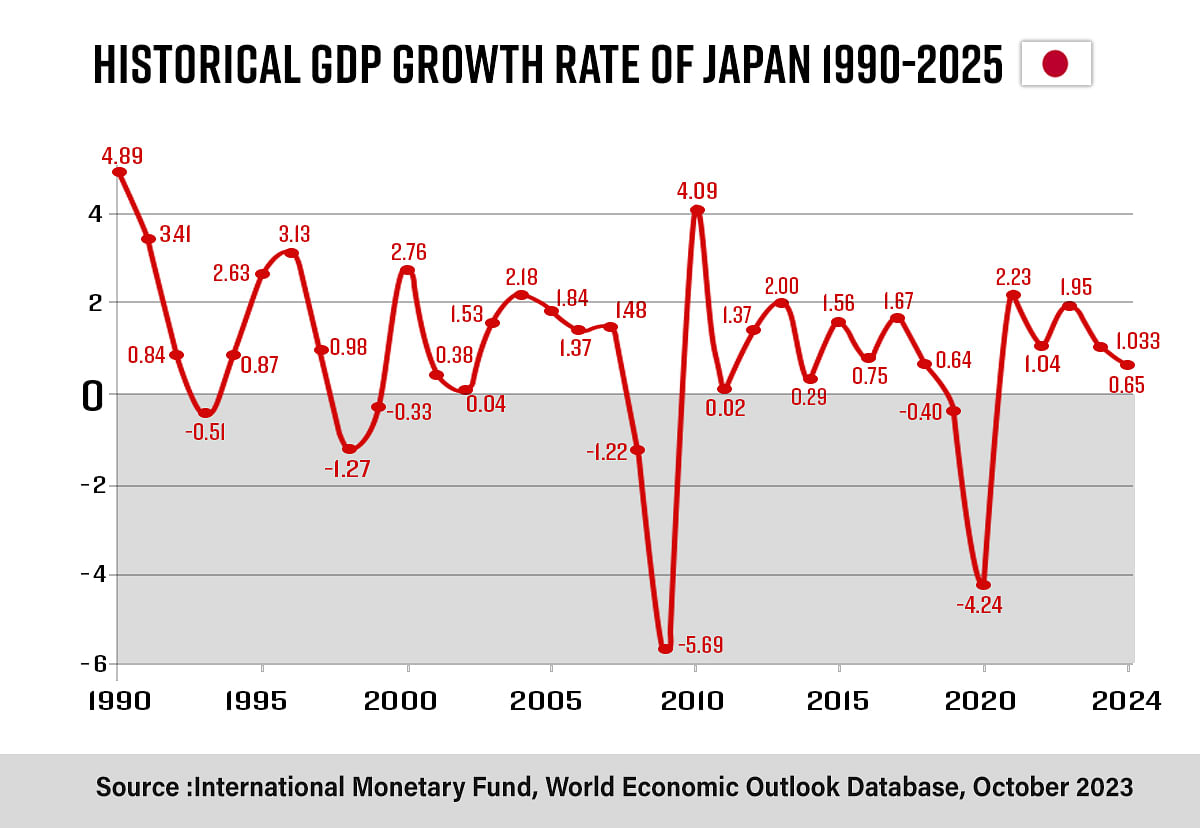

He highlighted that for about 23 years after World War II, the Japanese economy consistently had some of the highest growth rates, before plateauing at 4-5 percent till the 1990s.

Since the 1990s, the Japanese economy has grown over 3 percent in a single year only four times, according to the IMF data. It has had extremely low growth rates of around 1 percent for most of the last three decades — hence the moniker “the lost decades”.

While annual GDP growth in Japan remained low, its general government debt grew from 63 percent of the GDP in 1990 to a peak of 260 percent in 2022. Japan also faced demographic stagnation during this period, similar to the events occurring in China currently.

“The population in China is getting older and is going to be older. The country is going through a rapid demographic transition. The world is getting older, but this is happening much faster in China,” highlighted Naughton.

For about 20 years, Japan had an annual growth rate of about 5 percent of its GDP, before hitting the lost decades of 1990. Learning from this, Chinese President Xi Jinping is attempting to prevent such a situation from occurring in China, he pointed out.

Naughton added: “[President] Xi’s objective is not high growth but transforming the institutions of the economy into a high-tech advanced manufacturing economy. He is also looking for more effective steering of the economy by the government.”

Changing priorities for Chinese economy

Apart from centralising economic decision-making, the Chinese government under Xi has also changed its priorities from a high-growth economy to focus more on the “construction of a modernised industrialised system,” explained Naughton.

“In 2023, the top priority of the National People’s Congress and the government’s work report was expanding the domestic demand within the economy. In 2024, this has been demoted to the third priority. Modernising and accelerating the construction of a modernised industrialised system is the top priority,” he said.

Part of this fundamental transformation of the Chinese economy is an activist approach being undertaken by Beijing, especially in choosing sectors of the economy for future investment.

“In 2014, Beijing created a ‘Government Guidance Fund’, which was designed to be market reforming, like a venture capitalist fund, but sponsored by the government and its managing partners to guide the investment,” said Naughton.

According to him, the intention was to reform the economy using the government. “Between 2014 and 2020, the fund reached $1.5 trillion, highlighting the large commitment the government is willing to make,” he said.

A part of this stems from the Chinese strategy of “economic and technical self-reliance”, which, Naughton argued, became a part of Beijing’s policies in 2014, while the US and other countries have only started speaking about this recently.

The activist approach can be seen with “innovation consortia” being founded by the government in the realm of scientific engineering. The government has been giving these firms specific targets to achieve, claimed Naughton.

“The government is telling its firms that ‘we will give you the target and sign these contracts to meet these goals.’ The focus is investing in areas where China is not developing a competitive advantage,” said the expert.

“The fundamental change to Chinese economic policy, especially in macroeconomic outcomes and changes to the incentives by the government, has been combined with a change in the way policy-making systems function by Beijing,” added Naughton.

(Edited by Richa Mishra)

Also Read: ‘Shadow banking’, ‘rotten tails’ & mortgage boycotts — how China’s housing market unravelled

Indian funded comments