New Delhi: Despite its efforts to make it more expensive to borrow from banks, the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) interest rate hikes have failed to contain the demand for bank credit, an analysis of RBI’s data by ThePrint shows.

After freezing the repo rate throughout the Covid-19 pandemic at 4 per cent (April-2020 to April 2022), the RBI raised it for the first time in May 2022 to 4.4 per cent in response to rising inflation. Since then, the Central bank has hiked the rate intermittently by 185 basis points in total to 6.25 per cent as of December 2022.

The repo rate is the rate of interest at which the Central bank lends the commercial banks in case of shortage of funds. In theory, when the repo rate is hiked, the commercial banks would have to also charge a higher interest rate to borrowers. Consequently, a dearer loan should disincentivise borrowers and curtail their demands. Controlling credit in this way means that fewer people and companies take loans and it reduces demand, which in turn has a direct impact on slowing inflation.

This is the theory. Reality, however, doesn’t quite work this way.

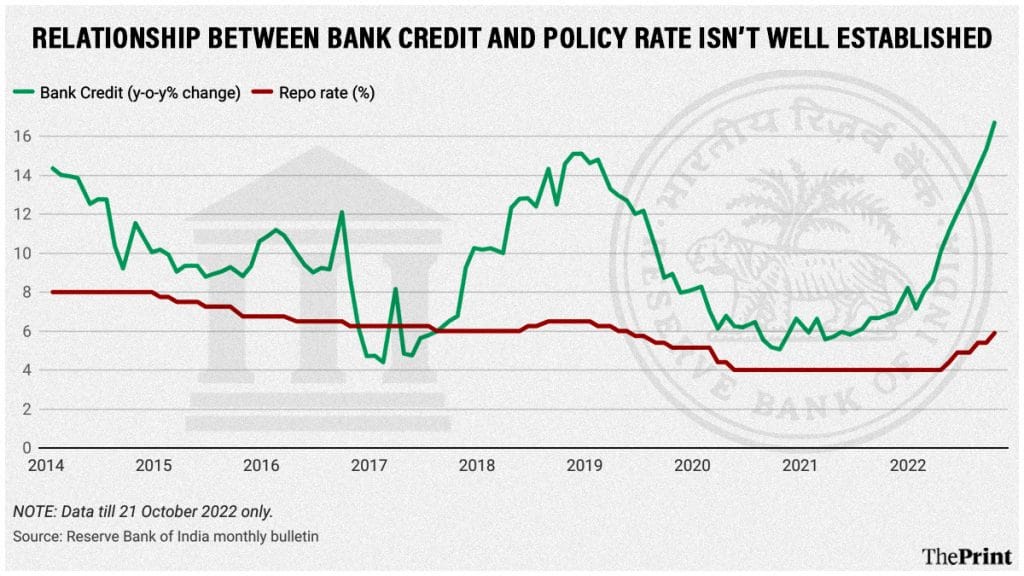

ThePrint analysed the RBI’s monthly data on bank credit against the repo rate changes made by the Central bank and found that bank credit growth was initially subdued while the repo rate was kept low (although this could have been the pandemic impact), but then began to grow and continued to grow at an accelerating rate even though the repo rate was hiked significantly over the subsequent months.

During the period May 2020 to March 2022, when the repo rate was kept at 4 per cent, the year-on-year growth in bank credit was an average of 6.4 per cent. By April 2022, this had grown to 10.1 per cent even though the repo rate was still unchanged.

Then, as the repo rate hikes started — 4.4 per cent in May, 4.9 per cent in June, 5.4 per cent in August, and 5.9 per cent in October — the growth in bank credit kept on accelerating to 16.7 per cent in October 2022, the latest month for which there is bank credit data available.

Also Read: Do Indian newsrooms get it right on economic trends? RBI has the answer

Where is it rising

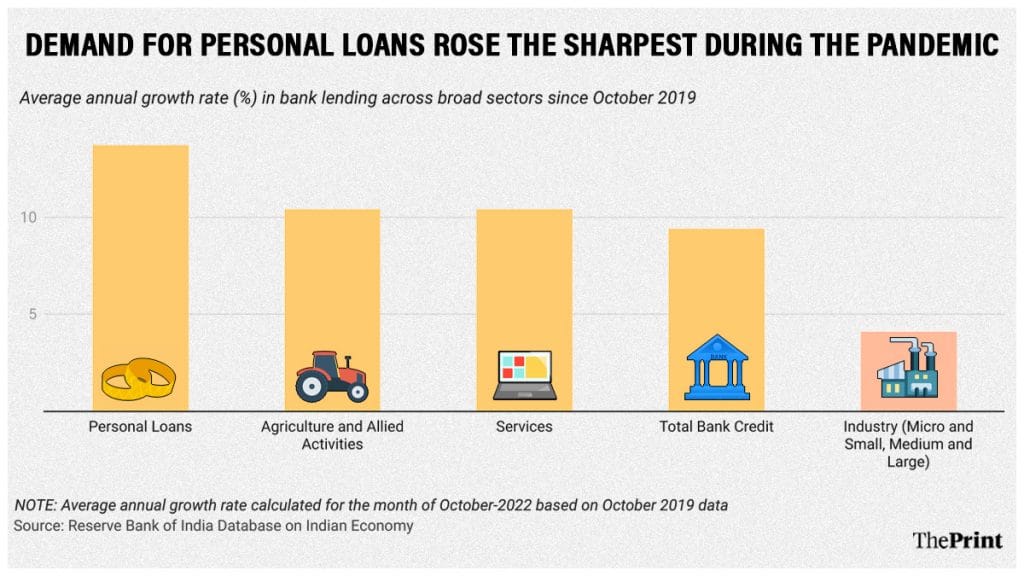

The RBI also gives sectoral data for the deployment of bank credit. Data shows that during and after the pandemic, bank credit to services and personal loans have witnessed the steepest rise. Since October 2019, overall bank credit has risen by 9.4 per cent on average, but many sectors have witnessed much larger growth.

Personal loans such as loans for consumer durables have grown by an annual average rate of 51 per cent, while those against jewellery have risen 44 per cent during the same period.

Trade services and services offered by non-banking financial corporations and public financial institutions, too, have witnessed a substantial growth rate.

However, the industrial sector has witnessed a modest growth of just 4.1 per cent in credit offtake. Although micro and small industries reported a 12.3 per cent growth in credit taken and medium industries recorded a 28.3 per cent annual average growth in bank credit, laggard growth in credit to large enterprises is pulling the growth down in this sector.

The large industries account for 76.5 per cent of the total bank credit to the industrial sector, and during Covid-19, credit to this segment has grown by just 1.3 per cent on an average for the past three years.

Factors responsible for rise in bank credit

Rising interest rates not being a deterrent for borrowing could be explained by multiple factors.

According to Radhika Pandey, Senior Fellow at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, the growth in credit could partly be attributed to ‘pent up demand’.

“Bank credit has shown a double-digit growth since the start of the current financial year,” Pandey told ThePrint. “This is despite a 225 basis points hike in the policy repo rate by the RBI. While a large part of the rise in credit is driven by personal loans and services, credit to industry has also seen a pick up in the current year.”

“Credit to industry, which was muted in 2021, saw a revival in the first two quarters of FY 2022-23. It grew by 9.47 per cent in the first quarter and further by 12.56 per cent in the second quarter,” she added.

She said that despite slow growth in credit to large industries, the pace is now picking up.

“Credit to large industries has also picked up. Corporate deleveraging cycle that started post March 2020 involving repayment of high cost bank loans by industries seems to have ended. Industries are now in a position to undertake fresh loans,” she explained.

She added that demand for personal loans could also explain some of this growth.

“Personal loans surge can be attributed to pent up demand. The demand for housing loans has seen a jump in the current year. Vehicle loans and consumer durables have also picked up indicating a revival of demand despite a rise in interest rates,” Pandey said.

RBI and lending

There is another hypothesis that may explain why the Central bank’s efforts to contain credit do not travel through the commercial banks.

In ThePrint’s ‘Off The Cuff’ event held last week, IMF Executive Director and former Chief Economic Advisor, K.V. Subramanian, explained how the link between the RBI’s steps and commercial banks’ activities goes against the conventional wisdom.

In that conversation, Subramanian explained that lending is essentially controlled by commercial banks, who account for 85 per cent of the money supply in the economy.

“When the global financial crisis happened, both my co-author and I observed that central banks across the world pulled out bazookas, big instruments to stimulate the economy, increase lending etc,” Subramanian said. “Almost one and a half decade later and even during Covid, when the same bazookas were fired, what we see is that these have turned out to be damp squibs.”

The reason why he believes the link is not well established lies in the bank’s discretion to lend, he explained.

“Irrespective of how much the Central banks persuade banks to lend, banks are going to assess the borrower’s ability to repay and then make a decision,” he said. “You have 85 per cent of the money supply with commercial banks and a monetary base — which is the domain of the RBI — dancing to two different tunes completely. Monetary theory links the two in such a way that doesn’t work in real life,” he added.

Asked if repo rate hikes are not having an impact on slowing down credit growth, should the rates then be reduced, Pandey said much of it depends on the rate of inflation.

“The repo rate would have had an impact but a large part of the rise (in credit growth) is explained by pent up demand,” she said. “It’s happening on a low base. And for large industries, it is a combination of loans for working capital (being taken) and the fact that the deleveraging cycle has ended and they’re in a position to take fresh loans.”

“The policy recommendations on slowing down on rate hikes or even lowering rates should be determined by the inflation trajectory,” she concluded.

On Thursday, the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation released data showing that retail inflation in December easing to 5.72 per cent from November’s 5.88 per cent.

(Edited by Geethalakshmi Ramanathan)

Also Read: How India’s economy fared in a year of shocks, aftershocks & slowing global growth