For the first time, the government’s labour survey will include the country’s vast informal sector, but not everyone is convinced it’ll signal creation of new jobs.

For those trying to solve the Indian economy jigsaw puzzle, reliable jobs data has been one crucial missing piece. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has a plan to fix that defect.

The government is set to map employment in the economy’s vast informal sector when the labour ministry starts publishing quarterly surveys on jobs in about a year’s time, covering enterprises with less than 10 people, including those who are self-employed. These are businesses that are typically cash-based and don’t pay tax.

“It’s a huge survey and takes the entire country into account,” B.N. Nanda, senior labour and employment adviser in India’s labour ministry, said in an interview at his office in New Delhi last week. “This will be the first informal sector data from the government, enterprise-wise.”

With more than 90 percent of India’s labour force estimated to work in the informal economy, a lack of periodic and credible data in this sector makes it difficult to assess the impact of policy actions and measure true growth.

Multiple data sets for formal jobs point in different directions, giving the perception that Modi has failed to generate employment. That’s denting his popularity among young voters ahead of next year’s election. He swept to power in May 2014 with the biggest electoral mandate in three decades after promising to create 10 million jobs each year for the country’s burgeoning youth population.

About 12 million young people are set to enter the workforce every year in Asia’s third-largest economy over the next two decades. The World Bank says India must create 8.1 million jobs a year to maintain its employment rate.

The state of joblessness is so dire that over 28 million people applied for about 90,000 vacancies this year at Indian Railways, the country’s biggest employer, while engineers and lawyers vie for low-skilled jobs in the government.

Labyrinth

Much of the government’s annual jobs data based on household surveys, which also captures the informal sector, is dated. The survey published for 2015-16 put the unemployment rate at 3.7 percent. The labour bureau will soon publish the data for 2016-17 — after a lag of two years — and has discontinued any more surveys, Nanda said.

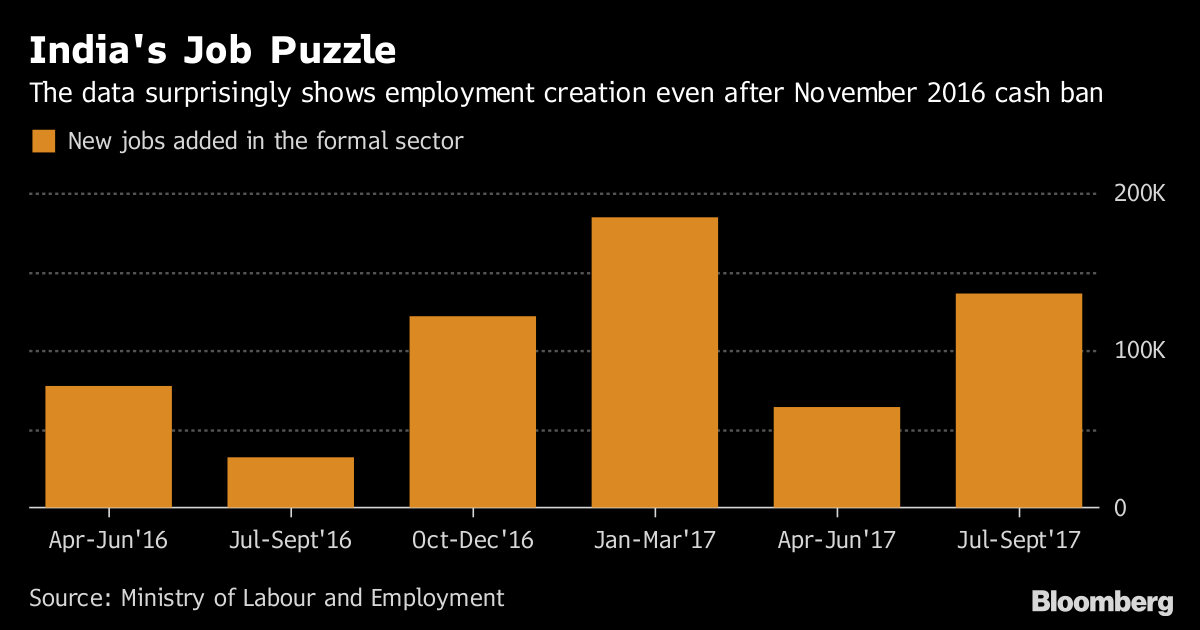

The organized sector, for which data is available from multiple sources, creates some confusion. The labour ministry’s figures released in March show India added 136,000 workers across eight sectors in the quarter starting July 2017, against 64,000 additions in the previous quarter.

The first set of data released by social security organizations in April showed over 3.5 million new payrolls were generated in the six months through February. The government said it’s an “eye opener” and puts an end to “speculations and conjectures regarding job creation.”

Bleak Picture

But not everyone bought the argument because payroll data could be more of a reflection of a formalization of jobs rather than a creation of new jobs.

“This, of course, is not employment data,” Mahesh Vyas of the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt., a business information company, wrote in a column published on CMIE’s website. “Growth in EPFO enrollments largely reflect the conversion of hitherto informally employed people into formal employment,” he said, referring to the Employees’ Provident Fund Organization data on payroll.

Private surveys paint a bleak picture. India’s jobless rate rose to 6.23 percent in March from 6.06 percent in February — the highest monthly rate in the past 15 months, data from CMIE show.

The statistics office has also started conducting surveys for generating estimates of various labour force indicators on a quarterly basis for urban areas and an annual basis for rural. The results of the surveys will be published this year.

The economy, which saw world-beating growth prior to a surprise cash ban in 2016, is forecast to have slumped to a four-year low of 6.6 percent in the fiscal year 2018 that ended March 31. Unemployment remained high even during the boom years and that led to Modi’s opponents concluding that the $2.3 trillion economy was seeing jobless growth. The International Monetary Fund sees India’s economic growth at 7.4 percent in fiscal year 2019.

“I don’t believe in all this talk about jobless growth because your economy cannot grow at 7.4 percent without employment,” said Nanda. “If productivity has not been spectacular and capital growth isn’t remarkable the growth is basically coming from employment.” – Bloomberg