Mumbai: Amol Hukkeri, a rural distributor for one of India’s largest fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies, Hindustan Unilever (HUL), has had a tough couple of months.

His business involves supplying the company’s products to kirana stores in distant villages of Maharashtra’s Kolhapur district. The products include some of the most common names found in Indian households, from soap bars Lux and Lifebuoy to laundry detergents Rin, Wheel and Surf Excel. However, torrential rains in the district have rendered several villages inaccessible in the talukas of Hatkanangale, Shahuwadi and Panhala, which he services.

“Market me barish ka bahut asar ho chuka hai. Bahut gaon me hum nahin ja sakte (the market has been affected by the rains and we have not been able to visit villages),” the Marathi native speaker says in broken Hindi.

Hukkeri now has his hopes pinned on the harvest season, which will decide the fate of his business in the coming months.

“Last year, we had patchy rain and now this year, we have had an excess of it. Both these extremes impact us as our sales depend on the crop harvest. About 80 percent of the population here depends on agriculture for income,” he adds.

The distributor estimates that his business clocks monthly sales of Rs 17.8 lakh on average, but with the heavy rains, the sales have taken a hit of 12 percent.

Not just Hukkeri but the entire consumer goods sector is waiting to see how the monsoon season ends and impacts the revival of demand and sales, which have slowed down in the last few quarters due to persistent food inflation that has shrunk consumers’ wallets.

As consumers struggle to keep up with rising household expenses, they have reduced their discretionary spending and purchases of premium products. The impact has so far been more pronounced in rural India, where consumers spend more on food compared to the urban areas.

The demand slowdown has hit the sales of companies across consumer segments.

FMCG companies, most of which derive a large share of their earnings from rural markets, have struggled to meet sales targets. So much so that HUL, arguably the biggest FMCG player, which garners about 40 percent of its sales from the rural areas, reported about 6 percent year-on-year (YoY) decline in its net profit to Rs 2,406 crore in the last quarter (Q4) of the financial year 2024, the biggest since the Covid-impacted quarter of January-March 2020.

The company, however, reported a 2.7 percent rise in net profit to Rs 2,538 crore YoY led by a slight recovery in rural sales in Q1 of FY25.

Another FMCG major, ITC, also reported a 4 percent YoY fall in profit for Q4 of FY24 to Rs 5,121 crore and then a marginal increase in profit in Q1 of FY25 to Rs 4,197 crore as compared to Rs 4,903 crore a year before.

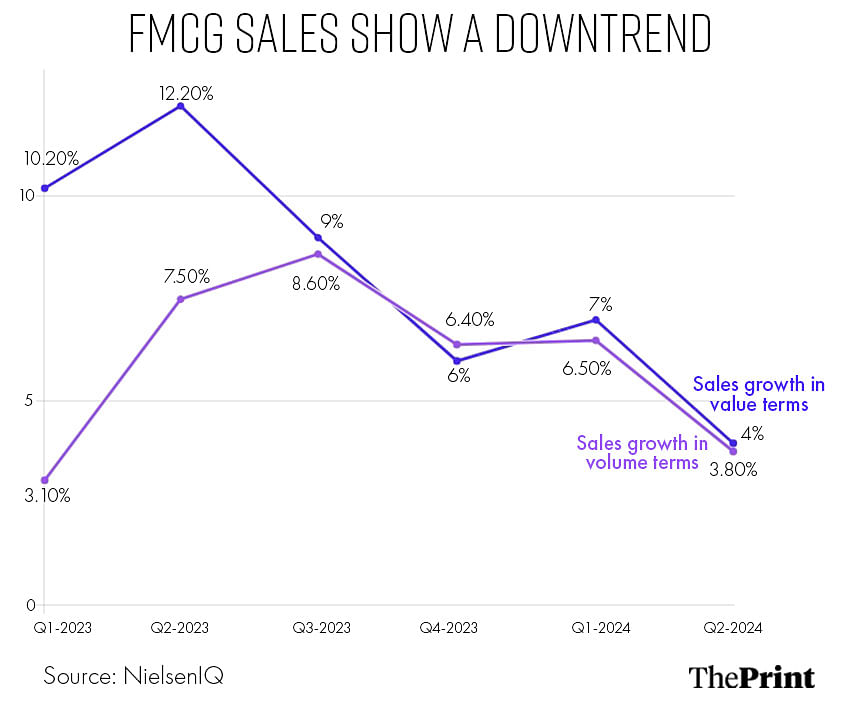

According to a report this month by consumer intelligence company NielsenIQ, FMCG sales volumes in India registered a low growth of 3.8 percent YoY in the April-June (Q2) quarter of the calendar year 2024 as compared to 7.5 percent witnessed in the same period last year. Sequentially, too, growth has seen a drop as sales volumes in the sector had grown by 6.5 percent in the January-March quarter (Q1).

Non-essential categories such as apparel, consumer durables and jewellery have taken a substantial hit. Fashion retailer Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail (ABFRL), the parent company of apparel brands such as Louis Philippe, Van Heusen, Allen Solly, Peter England and multi-brand retail chain Pantaloons, has reported losses for the last five consecutive quarters.

The company reported a net loss of Rs 628 crore in FY24 as compared to Rs 36 crore in FY23. Other retailers such as Shoppers Stop, Bata India, and Metro Brands have registered a decline in their profits for the last few quarters, if not losses.

Though most consumer goods companies cater to essential needs such as food or clothing, they are sensitive to economic slowdown as consumers start downgrading, which is buying less expensive products, smaller packs and even smaller quantities in times of distress.

Emerging out of Covid, retail and consumer goods companies had witnessed a pick-up in demand and subsequent revival; however, sky-high inflation in edible oil and other key commodities halted their growth. Even as edible oil inflation abated, food inflation picked up in the country with subpar monsoons last year, following which most companies reported a downfall in demand from the second quarter of FY24.

The festive season in 2023 offered a momentary relief but then a short wedding season could not push up sales much. The entire consumer goods industry now has its fingers crossed for a normal monsoon and is hoping that the wedding season this year, which is longer than usual, will bring consumers to its fold.

The Reserve Bank of India’s July 2024 round of bimonthly survey on consumer confidence indicated a downswing in consumer sentiment. Consumer confidence fell for the second consecutive survey after being on the rise since the end of the pandemic.

The report said consumer sentiment on major parameters such as economic situation, employment, price level and income, except for spending, had moderated and, as a result, the current situation index fell to 93.9 in July 2024 from 97.1 two months earlier.

The latest round of the survey was conducted during 2-11 July and covered 6,062 respondents.

Also Read: Private sector green shoots & strong manufacturing, but elevated inflation: India’s FY24 report card

It’s all about food

It is no revelation that in India’s agrarian economy, monsoons decide the fate of the country for that year. While too little of it can dry out the crops, too much of it can cause rot. Either way, the harvest of kharif or monsoon crops such as paddy, maize, jawar, bajra and tur is impacted, leading to poor farm income, which in turn causes lower spending in the rural economy and impacts sales of consumer goods across segments.

The year 2023 was supposed to be a “normal” year for the consumer sector after the Indian economy emerged from the challenges of the pandemic in 2021 and then subsequent high commodity inflation in 2022 due to supply constraints, geo-political tensions and other reasons, but a sluggish monsoon impacted its recovery.

Economists say that below-normal rains last season not only led to a decline in kharif output and rural income, but also led to a rise in inflation, particularly in the food basket.

“If you leave out July (this year), in the last 12 months we have seen inflation peak out and most of it is because of food. Food inflation started to rise last July and continues to stay high,” says Dipti Deshpande, principal economist at CRISIL, an analytics company that provides ratings, research, risk and policy advisory services.

Last year, weather disruptions such as delayed, below-normal and patchy monsoons and heat waves impacted the crops of most consumed vegetables such as onion, tomato, and garlic, and foodgrains such as pulses, leading to high food inflation.

“Vegetables and foodgrains comprise about 50 percent of the food index. Inflation in foodgrains in the past year has been at about 11 percent as opposed to the typical trend of 6 percent. Similarly, in vegetables, the inflation rate usually is about 7.5 percent but we have seen it at about 24 percent,” says Deshpande.

“The food inflation rate for the last two consecutive years was higher than what it normally tends to be. The long-term average for food inflation would be at about 6 percent. In fiscal 2023-24, it was at 7.5 percent and the year before that, it was at 6.8 percent. So, food is pinching the average consumer more,” she adds.

Burdened with high inflation in common food items such as vegetables and pulses, the consumer now has to shell out more for these products and hence has lower capacity to spend on other consumer categories. The development has especially impacted the economically weaker sections and rural consumers, who spend more on food purchases.

Sharvi Modak, a domestic help residing in Nalasopara, a town in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region, is a case in point.

The 52-year-old and her husband collectively earn Rs 40,000 per month. However, they have barely any savings left for other expenditure after paying for food, rent and college fees for their two children.

“Before Covid, we would save some money out of our income and eat out or buy clothes, but now we cannot afford these things,” says Modak.

“Most of the time, we buy groceries for the month on credit now and pay the shopkeeper in our neighbourhood next month,” she adds.

An average consumer in the rural areas of India spends about 46.4 percent of their earnings on buying food, while one in the urban areas spends just 39.2 percent, according to the government’s All India Household Consumption Expenditure Survey for 2022-2023, released this February.

What’s selling, what’s not

Pradeep Kirana Stores located in Ambikapur in Chhattisgarh, about 337 km away from capital Raipur, has served the grocery needs of the small town since the 1980s. While some of its customers are from a middle-income neighbourhood in the town, its major business comes from rural consumers who throng to Ambikapur, the headquarters of Surguja district, often.

The owners, hence, have a pulse of the rural market surrounding the district and stock their products depending on the demand from these consumers.

“We have seen a slowdown in demand for discretionary products such as deodorants, body lotions and face creams. Consumers have also switched back to smaller pack sizes and now prefer to buy small packs even though they may have to make frequent visits. Therefore, we have reduced the stock of large bottles of shampoos, body lotions etc,” says Satyendra Kumar, owner of the retail outlet.

Grappling with inflation, consumers have reduced their spending on consumer products, especially those in the discretionary or non-essential needs categories.

K. Ramakrishnan, managing director-South Asia, Worldpanel Division, at market research company Kantar, explains that the general response by consumers to inflationary pressures from the household perspective is to spread the purchases across more occasions.

“This is why India has seen growth in the number of FMCG-specific shopping trips. However, that growth has slowed down now. Shoppers are continuing to reduce their pack sizes as much as possible, and that consumption decline is being reflected in the volume slowdown,” he says.

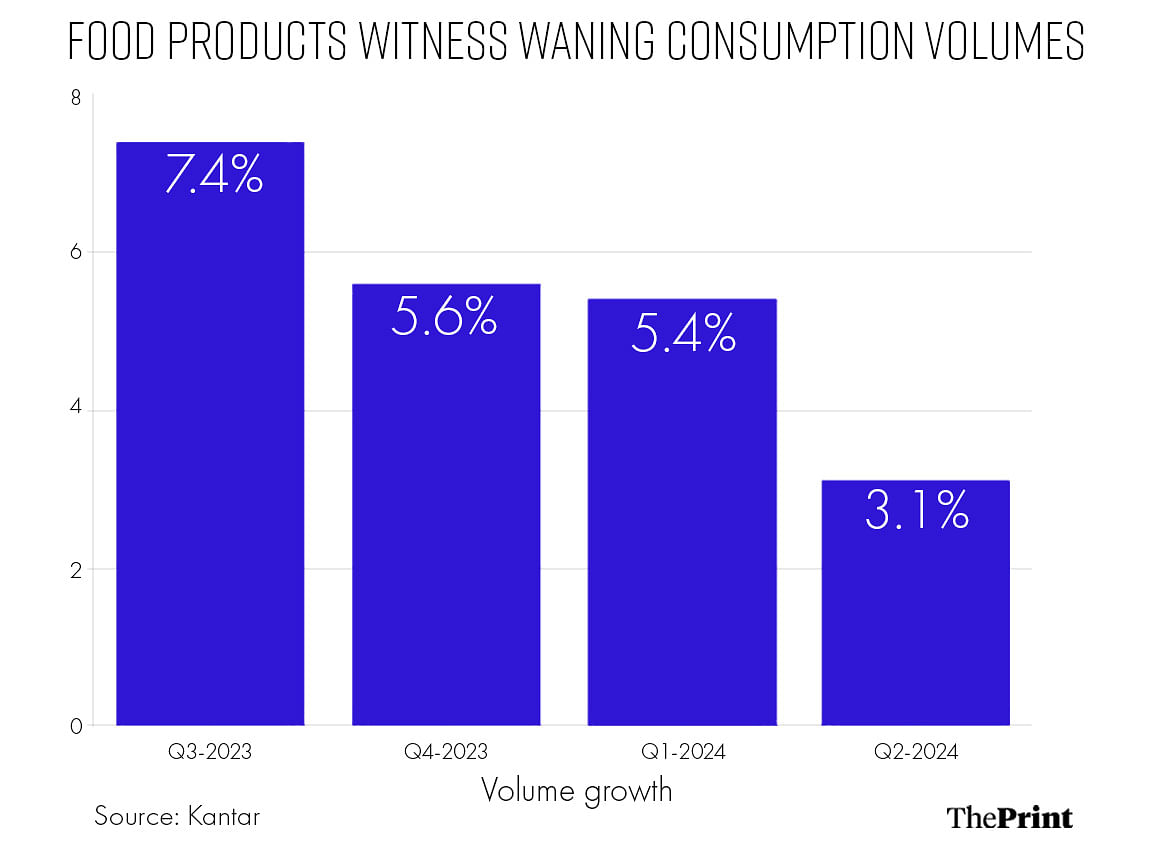

According to Kantar, FMCG volume growth or in-home consumption growth slowed to 4.6 percent in the June quarter of CY2024 from 6.8 percent growth witnessed in the September quarter of 2023. The worst-affected segment, it reported, was that of food, while others such as household care and beverages, performed marginally better.

“The reduction in foods can be attributed to two main segments—staples and snacking. Staples such as spices, atta and tea have seen a slowdown in growth. The edible oil category is still to recover entirely. Therefore, the growth of the staple has steadily fallen from 6.8 percent in the September quarter of 2023 to 2.5 percent in the June quarter of 2024,” says Ramakrishnan.

In the snacking category, biscuits, noodles and savoury items have witnessed a downturn in growth, according to Kantar.

One of the largest sellers of biscuits and confectionaries, Parle Products, also reported slow sales of premium bakery products.

“The consumer seems to be willing to spend on low-ticket items rather than the higher-priced products. For instance, in the bakery segment, where we have rusk and cakes, we have not seen much demand coming from the rural market. The mass market products, however, continue to perform well,” says Krishnarao Buddha, senior category head at Parle Products.

The company, which houses brands such as Parle-G, Hide & Seek and Monaco, garners about 55 percent of its revenue from the rural market.

In the urban areas too, experts believe, spending by affluent households on discretionary products has reduced, which has resulted in waning sales of these products.

“Affluent households tend to spend more on the discretionary categories and they drove the growth of these products over the last two years post-pandemic. But now with the decline in the services sector in cities, the spending has slowed down and impacted the demand for these products,” says Anand Ramanathan, Partner, Deloitte India.

A Consumer Spending Survey by Deloitte in June observed that spending intentions by consumers have declined since January 2023, with a brief recovery around the festive shopping season last year. Discretionary spending intent witnessed a reduction of about 10% compared with non-discretionary expenditures, the survey noted.

The value play

Apparel retail, though a non-discretionary category, has been one of the hardest hit by the consumption slowdown. The Clothing Manufacturers Association of India (CMAI) estimates that the segment saw an abysmal growth of 2-3 percent in FY24 as compared to FY23.

“Sales growth in the first quarter of FY25 would also be in the same range,” says Rahul Mehta, chief mentor, CMAI.

While retailers such as Shoppers Stop and Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail have reported a decline in sales, value retailers such as Zudio by Trent, V-Mart Retail and Style Union are faring much better, indicated market watchers.

Fashion retailer V-Mart Retail, which runs over 450 stores across tier 1, 2, 3 and 4 towns, has reduced its average selling price by 5-6 percent in a bid to achieve better sales.

“Products below Rs 1,000 are seeing more traction from consumers while the sales of products priced in the higher range remains sluggish,” says Vineet Jain, chief operating officer, V-Mart Retail.

According to industry stakeholders, apparel is now competing with several other categories such as gadgets for a share of the consumer’s wallet, and this, too, has led to a fall in sales.

“The online discounting strategy has also impaired the overall brand image. Most apparel brands are available on discounts of up to 30-50 percent almost throughout the year and clothes are no longer seen as status symbols,” says Mehta.

The pinched consumer wallets have also impacted the sales of consumer durable products and jewellery brands.

“The consumer durables segment was growing at a compound annual growth rate of 11-12 percent for the past 10 years (excluding the pandemic-impacted years). But for the last two years, we have not seen growth beyond 8 percent for the industry,” says Kamal Nandi, business head and executive vice-president at Godrej Appliances.

The appliances category, too, is witnessing higher sales of products positioned in the mass segment as compared to the premium.

According to Nandi, premium products witnessed higher demand with the subsiding of the COVID-19 pandemic, but with the onset of summer this year, the sales for mass products have picked up again.

Hope from festive demand

Some green shoots have emerged of late in the consumer goods sector with the prediction of adequate monsoons this season, which is expected to further quell inflation.

Rohit Jawa, CEO and MD of Hindustan Unilever, indicated that the company has seen some green shoots in the rural areas during the April-June quarter of FY25 after two years of stagnant sales.

Other consumer goods companies have also witnessed a similar trend.

“Moderating inflation, improving agriculture terms of trade, an expectation of normal monsoons and the government’s thrust on public infrastructure and the rural sector augur well for a pick-up in consumption demand, building on the green shoots of recovery that are visible in rural markets,” ITC said in a statement while reporting its financials for the first quarter of FY25.

Experts, however, are divided on the outlook for the rural economy and inflation going ahead.

The FMCG expectations have been riding on the projections of a normal monsoon. However, some reports say the monsoon this year also could be skewed. Given the fact that the base effect has come into play and led to a downtrend in inflation, further relief from it could still take time.

“The price pressure is still there, especially, in pulses. The sowing of pulses has lagged when compared with 2022, a year which had seen normal sowing. Although rural is seeing recovery, urban consumption is showing initial signs of worry, especially, with indicators like passenger vehicle sales. So, we are not out of the woods yet,” says Sarbartho Mukherjee, senior economist at CareEdge Group.

Industry watchers, however, believe the upcoming festive season coupled with the wedding season will help in reviving demand in the economy. The festive season accounts for 35-40 percent of annual sales for the retail companies.

“Expectations are quite high from the festive and the wedding season. The wedding season this year is going up till June so this might spur consumer spending,” says Mehta of CMAI.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: In India, households optimistic about state of economy despite rising debt, expect inflation to ease

What a well researched article with so many on the ground accounts from different people involved. Too good. You even added lot of data and analysis to substantiate the points. Was missing this kind of journalism in this era of sensational and twitter reporting. Kudos and keep it up.

7,00,000 unsold cars in showrooms. Leaders of organised retail closing stores, letting go off tens of thousand of employees. Private consumption and private investment two out of four engines that are not firing on all cylinders. Merchandise exports sluggish. Government capital spending cannot keep the economy aloft on its own.