Stock market regulator Sebi’s ‘high-risk’ countries measure reeks of bureaucratic overkill.

Wealthy Indians living overseas are reliable lenders of last-resort dollars, to be tapped whenever New Delhi loses control of its balance of payments. Except when the same people try to pool equity investments from overseas for their home country; then they’re money launderers.

That, in a nutshell, is how the Indian authorities view nonresident Indians. And it leaves fund managers in a bind.

Their custodians have been asked by India’s stock-market regulator to come up with a list of “high-risk” countries. Any investing vehicle from those economies with a 10 per cent or greater beneficial owner will have to perform stringent know-your-customer checks. And if the person happens to be Indian, he or she simply won’t be allowed to invest in India that way. Even if no such large single beneficial owner exists, the manager controlling the fund with even a sliver of equity can’t escape scrutiny. Is she Indian? If yes, she must wind up the fund or change its structure.

The measures reek of bureaucratic overkill. Odder still, the SEBI’s original April order didn’t even specify the high-risk jurisdictions. Left to come up with their own lists, custodians are going crazy. Apart from the usual tax havens like the Cayman Islands and the Isle of Man, one tally I saw includes China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Thailand and the Philippines.

The funds’ custodians are global banks with sizable operations in these countries. Just imagine the embarrassment when an investment bank angling for a slice of the much-awaited Saudi Aramco IPO is asked by Riyadh to explain why it’s been portraying the kingdom to the Indian authorities as a high-risk country.

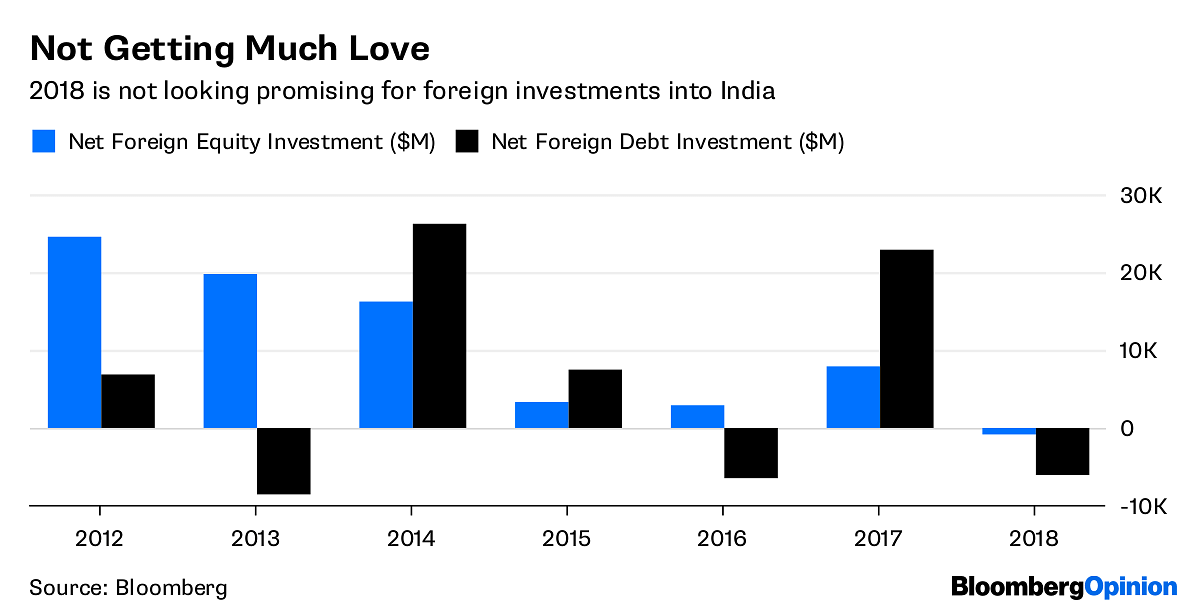

Foreigners have taken $740 million out of India’s equity markets so far this year; bond markets have witnessed a sharper pullback, of $6.1 billion. Any delay in the revival of inflows by December may see the Indian government (or state-directed banks) hawk fixed-income securities (or bank deposits) to non-resident Indians to fend off attacks on the rupee, repeating the pattern of issuance in 1998, 2000 and 2013, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

It’s puzzling that just when India needs dollars – the rupee is the worst-performing Asian currency so far this year – Indian managers, who presumably have an edge in mobilizing flows to their country, are told not to have skin in the game. The illogical tweaks in the investing rules have custodians worried about whom they can do business with; before confusion turns into disruption, the tinkering needs to stop. – Bloomberg

Nothing more fungible in the world than a hundred dollar bill. India’ s central government is now paying close to 8% to borrow at home, the equally stressed state governments about 8.5%. Appetite for their bonds – the “sovereign guarantee “ is looking a little jaded now, just as few Indians believe any longer that there is nothing safer in the world than money in the bank – is drying up. 2. Does it really matter to an increasingly desperate borrower who his lender is ? At the heart of these nitpicking rules is the eternal quest to uncover “ black money “ and to maximise tax revenues which cannot possibly be buoyant in a moribund economy. The entire demonetisation caper was part of this exercise. Entirely possible that the next government will inherit in 2019 an economy much more sickly than it was in 2014.