There’s been much excitement about the latest UN General Assembly vote on the Israel-Hamas war, which called for an immediate ceasefire. The resolution has been passed, and it passed with very large numbers.

There is a lot of criticism of the Modi government and India from many of the countries who don’t like India or who don’t like the current positions that the Government of India has on Israel and from many political parties in India who have a different position on Israel and on Palestine.

This vote at the UNGA, if you just see the numbers, it would seem India was sort of in a minority. How did India land up in such a minority? Is it such a good thing?

Look at the numbers: 120 voted in favour of the resolution — which means the resolution is against Israel, it’s adverse to Israel — and only 14 voted against it. These 14 are usual suspects, the Western block, in particular…Europe and American allies. Then there are 45 who abstained. India is among those 45.

The 120 who voted in favour are pretty much the entire so-called Global South that the Modi government has been talking about lately.

Of the 14 who voted against the resolution, the US is the most prominent. Of course, you would expect Israel to vote against it. There’s also a whole bunch of small nations in the Pacific like Fiji, Tonga, Nauru. And there is Hungary.

Hungary stands out in Europe, which is very interesting because on many other issues (EU and NATO issues), Hungary has taken a different position. Remember, Viktor Orban — the only Western or NATO leader — was present at Xi Jinping’s third BRI forum just the other day in Beijing. Now Hungary has voted with the US.

Also Read: Israel is angry, Netanyahu poised for Gaza invasion. But there are limitations to military power

First of all, the criticism that India has been caught isolated or maybe India is on the wrong side of history. One thing I agree with, and that’s my criticism as well (my opinion), is that once again, this is a reminder that India’s larger national interest, India’s global positioning, India’s strategic positioning and interest does not lie with the so-called Global South. The so-called Global South is aligned much more closely with China.

That doesn’t mean India should begin to ignore the Global South. India should not behave like a jilted lover because nobody was anybody’s lover. And, in any case, in global politics, nobody’s ever anybody’s lover. India can keep wooing the Global South, particularly if it causes the Chinese any consternation. But to go on and on with that mantra or raga as the Modi government has done lately is not necessary. Who does it impress? Certainly, it doesn’t impress the nations of the so-called Global South because all nations act in what they see as their national interest.

In this case, India has voted the way it has because India sees this as their national interest.

Ambassador @PatelYojna, Deputy Permanent Representative, delivered the explanation of India's vote at the 10th #UNGA Emergency Special Session today

Statement: https://t.co/6tOLVQnNv4 pic.twitter.com/phbvs5GiP8

— India at UN, NY (@IndiaUNNewYork) October 27, 2023

Now, coming to the second point, and it’s very important: This is not the first time in the history of the UN that India has found itself in such a dreadful minority over a UN General Assembly resolution.

The difference, however, is that this is the first time India finds itself in what you might see as a minority because it has acted on its own, because it has made a conscious choice. In the past, India might have found itself in a minority when it wasn’t a resolution of India’s choice because that resolution involved India — it was a resolution that ran adverse to its interests. And India had no choice but to vote against it.

Also Read: Amid strained ties, India backs Canada-proposed amendment condemning Hamas to UN resolution on Gaza

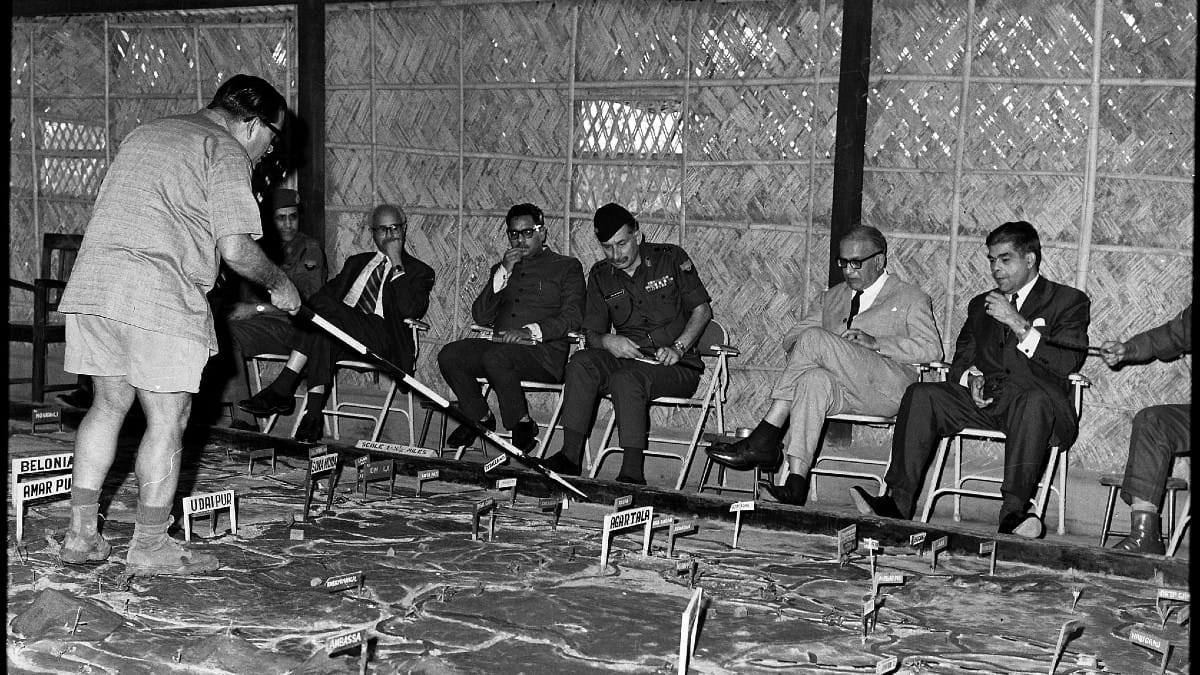

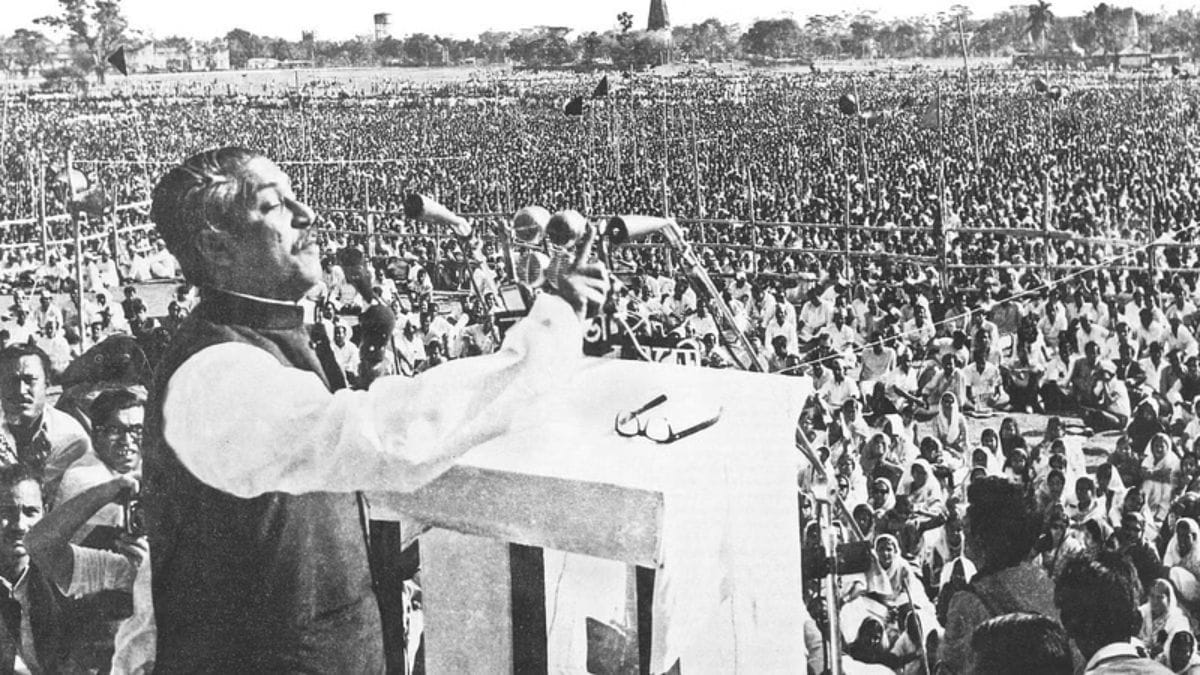

I’m you back to 8 December 1971 — it was the fifth day of the Bangladesh War. It was a 13-day war, which formally began on 3 December. The UN General Assembly discussed the war situation and moved a resolution asking India and Pakistan to cease fire and go back to where they were.

What happened in that resolution? Because that resolution affected India. As you would expect, India voted against it. There was a The New York Times headline of 8 December 1971. It says ‘U.N. Assembly, 104-11, urges truce’.

A resolution that was adverse to India’s interest was passed 104-11 and yet it had no meaning at a time when India was not such a strong country. There were also 10 abstentions.

This resolution was introduced by Argentina. If you see who voted against India, you would know the geopolitics of the era because it was the peak of the Cold War.

The 11 who voted with India are the Soviet Union, as you would expect, again, Bhutan, as you would expect — that was a very special relationship — Bulgaria, Byelorussia, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Mongolia, Poland and Ukraine. All of these were Soviet Union’s allies. And then the 11th, of course, was India.

The 10 abstentions are also important. Afghanistan always had a special relationship with India. I do not believe, at least until the mujahideen took over, that Afghanistan ever voted against India. Afghanistan abstained, Chile, Denmark, France, Malawi, Nepal, Oman, Senegal, Singapore and the UK.

The resolution came when India’s Army was marching into Bangladesh, marching into what was then East Pakistan and it looked like the Pakistanis were losing very rapidly. The Pakistanis were retreating across the eastern frontier. If you had to carry out this resolution and stop the fighting, it would only affect India’s interests negatively. It was in India’s interest for the fighting to continue until Bangladesh was liberated.

To counter it, the Soviets also moved their own resolution in the General Assembly calling for a ceasefire, but at the same time calling for a lasting solution to the East Pakistan problem. It meant Pakistan had to accept that their country would be divided. That was not acceptable to Pakistan and to its superpower friends, at that time, including the US and China.

The People’s Republic of China had become a permanent member of the United Nations just weeks earlier, on 25 November, replacing the Republic of China or Taiwan. That was following the Nixon-Kissinger-Zhou Enlai detente brokered by the Pakistanis. It was in that adverse situation that India faced this resolution and found itself in such a minority.

I will quote a couple of lines from the NYT story on the discussions in the UN General Assembly. The Nicaraguan Representative, Jose Roman, said and NYT quotes him: “We are concerned for the destiny of the United Nations. If it cannot resolve this problem in a definitive way, it will be just a bureaucratic lump of sugar.”

The fact is the UN failed to resolve that problem in a definitive way. Not only that, it has failed to even touch that problem since then. Because after the 1971 war, the liberation of Bangladesh, the surrender of Pakistan’s Army, the Shimla Agreement, the UN Security Council resolutions of 1948-49, all of that became so much water down the Indus, nobody cares about the UN anymore.

If you were to put the UN General Assembly to this Nicaraguan test in 1971, then it would be just a bureaucratic lump of sugar.

That session of the UN General Assembly also saw the Chinese out in their full colours. Until then, very often, India and China had voted on the same side. India also voted in favour of China becoming a member of the UN or People’s Republic of China taking the Republic of China’s place. That was a natural position for India to take.

The Chinese representative, however, said in the UN General Assembly and I quote from him from the NYT story: “The Soviet Government is the boss behind the Indian aggressors. The Indian expansionists usually do not have much guts. Why have they become so flagrant now? The reason is that a superpower, Soviet social-imperialism, is backing them up.”

The Soviet delegate there, Yakov A. Malik, hit back and said China was using the United Nations as a forum for, and I quote from him, “slander and anti‐Sovietism” — which he described as a “sordid task”.

Also Read: All about UN Security Council and India’s non-permanent membership

This is to make a limited point that it is not the first time for any country to look like it is in a minority in the UN General Assembly. Israel has traditionally always been in this similar minority in the UNGA. What matters at the UN, if at all, is the Security Council and that’s where the permanent members matter and they have the veto.

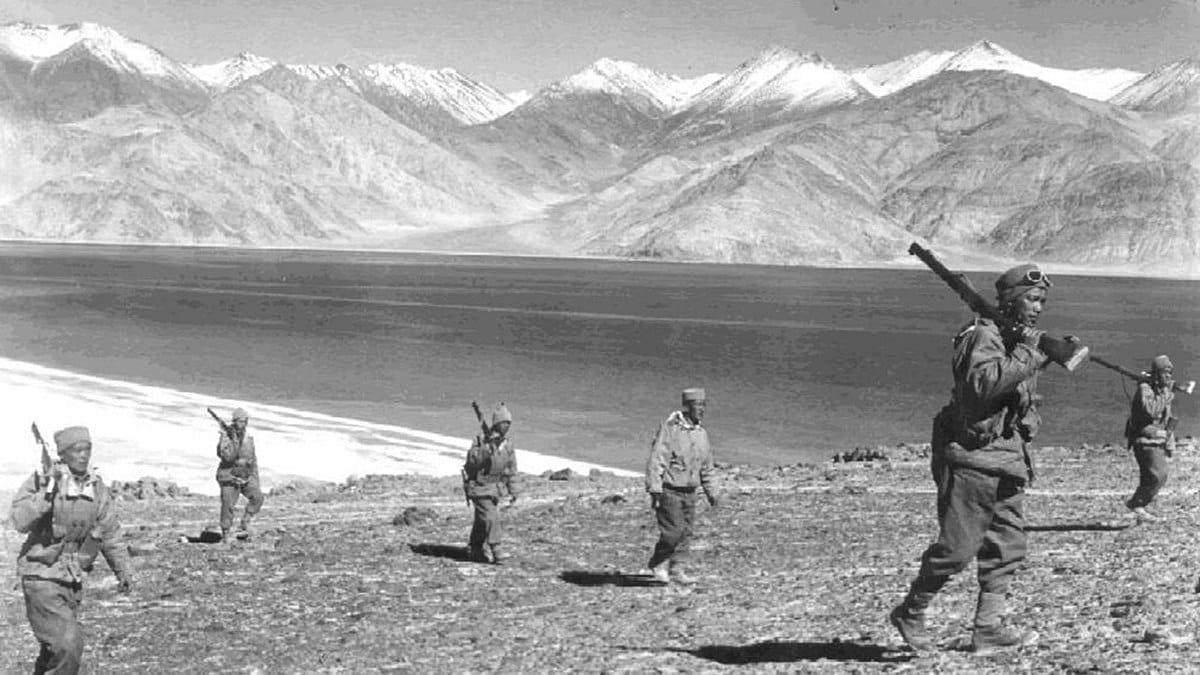

India, for example, did have a lot of discomfort at the UN on the Kashmir issue until the victory of 1971 and the Shimla Accord that followed. Who protected India then? Six times the veto power was used by the Soviet Union: Once in 1957, then in 1961 and 1962 and thrice during the 1971 war.

Thrice during the 1971 war one can understand, but 1962? How did the Soviets exercise their veto? Because in the winter of 1962, India was fighting a war with the Chinese. India was in trouble, India was under pressure, and the Western powers got into the act. They thought this was the time to put pressure on India to settle with Pakistan on Kashmir.

They then got a resolution moved at the Security Council. Somebody nudged Ireland to move it on behalf of the Western powers, directing India and Pakistan to begin negotiations to resolve the Jammu and Kashmir issue.

Ten members of the Security Council voted in favour. Imagine how strong a move it was to pressure India at a time when it had its back to the wall, under pressure from the Chinese who were advancing across the entire front. That is when the Soviets used their veto for the second time.

The first time was in February 1957. That is when Pakistan had moved something through the US, asking UN troops to play an active role on the ground to demilitarise Kashmir so that the situation could be created for a plebiscite.

Once again, in each of these situations, India was in a big minority. It didn’t bother anybody because ultimately the UNGA is nothing more than what the frustrated or angry Nicaraguan representative described it to be in 1971: A “bureaucratic lump of sugar”.

These numbers don’t matter. What matters is the position each country takes in these votes because that tells you that country’s national position on a big polarising global issue. And that is the position this time India has taken on Israel.

Also Read: In a first, India votes in favour of Israel at UN against Palestine human rights body

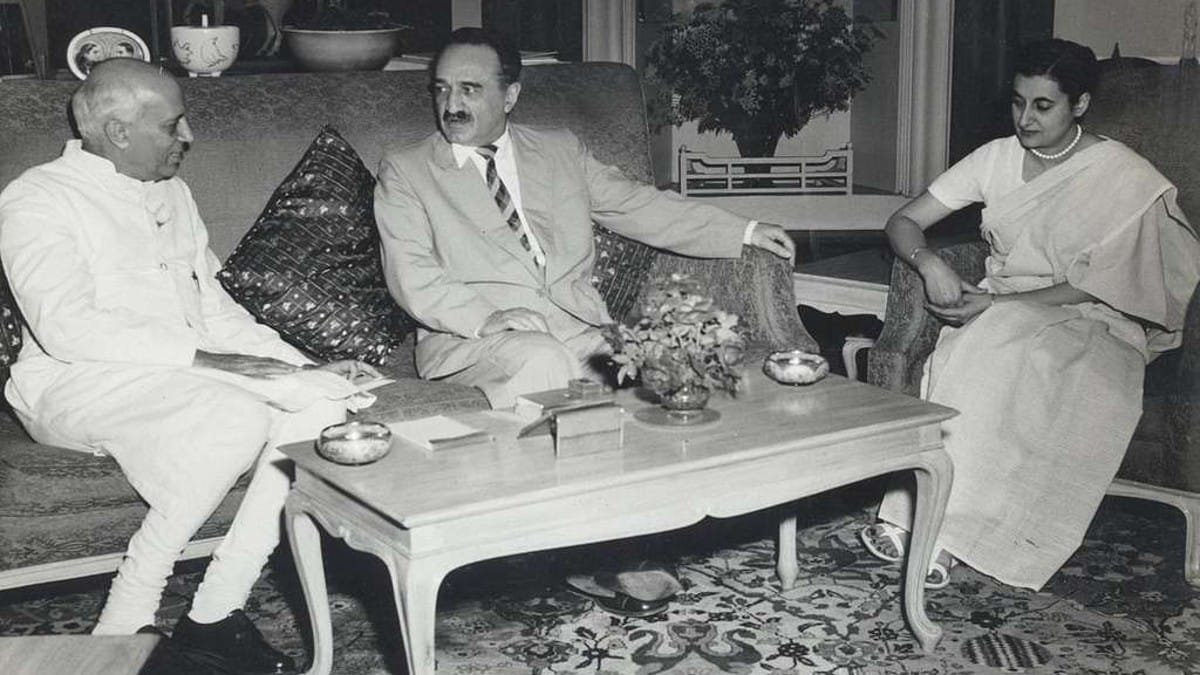

India’s voting record on Israel has seen a dramatic shift over time. Traditionally, India’s position had been anti-Israel. India was the only non-Arab state in 1948 that voted against Israel’s admission to the UN. At that time, Jawaharlal Nehru was the prime minister.

Similarly, when Indira Gandhi was the prime minister in 1975, India was the only non-Arab state voting in favour of the PLO and Yasser Arafat being recognised as the sole representatives of the Palestinian people at the UN. And then India recognized the PLO as the only representatives of the Palestinian people and also allowed them to open their office in Delhi. That was 17 years before India upgraded its relations with Israel to full diplomatic level.

Even in the sporting arena, India opposed Israel. In 1975, India hosted the world table tennis championships and did not issue visas to the Israeli team. India was fined $10,000. In 1987, in the Davis Cup quarterfinals — Rajiv Gandhi was in power — India initially demurred but finally agreed to play Israel and, just as well, because India won that Davis Cup quarterfinal.

Before that, once India had sacrificed its chances of winning the Davis Cup altogether because India was drawn to play the final against South Africa. India refused to play on grounds of Apartheid. And that’s how India forfeited its best chance of winning the Davis Cup to the South Africans. But that is still principled, that is on a high principle, that is Apartheid.

On Israel, a dramatic shift came in India’s view but not with that upgradation of their relationship in January 1992.

Just before that, in December 1991, India had voted for a US resolution against an earlier resolution that equated Zionism with racism and racial discrimination. This was the first time that India formally and openly voted in favour of Israel. When that happened in December, those of us who were active reporters covering the foreign affairs beat, we should have noted that some kind of change was coming.

Within a month and a half, India dramatically announced that it was upgrading its relations with Israel to full diplomatic level. Narasimha Rao did so on a day Yasser Arafat was in Delhi. He had spoken with him and got him to endorse India’s actions. Yasser Arafat was asked if he supported the move and he said, ‘yes, that’s a good idea because now peace talks are going on’.

That was the era of the Oslo talks. And he said, just as the Narasimha Rao government had said, that to have Indians present as friends in those talks or in that environment, having Indians present in Israel will be a good idea.

This is the edited transcript of ThePrint Cut The Clutter Episode 1338, published on 30 October 2023.

Also Read: In this war of dead baby pictures, yours versus mine, the question of who’s the victim will be lost