Even as Indians celebrated freedom at midnight, the Director General of the Intelligence Bureau warned that darkness lay ahead. Large parts of the country, B.N. Mullick bleakly observed in a 1953 official report, had seen the disintegration of the police ‘as an effective force’. “The old fear which the police used to inspire among criminals has largely dissipated,” he went on, the result of poor training and personnel shortages. “There has been no improvement in the methods of investigation or in the application of science.”

For 70 years—as India battled multiple insurgencies, large-scale communal violence, and caste conflagrations—annual reports by the central government have cut and pasted the same depressing data on which the legendary spymaster based his insights.

The editorial language has blunted because of bureaucratic timorousness perhaps, or plain-vanilla fatigue. But the reality of the Indian police still hasn’t changed.

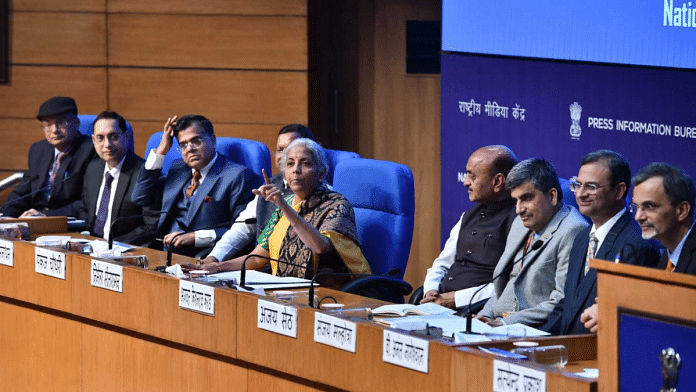

Like every year, Budget 2023 is certain to provoke energetic debates on defence spending. The hollowing-out of the core of India’s internal security—its police forces—passes without mention. The Constitution vests responsibility for the police with state governments. Leaving aside the Rs 2,780.88 crore the Budget commits to reimburse police forces of states fighting insurgencies, the central government is responsible only for the forces it directly maintains.

The story of the Indian police is, so to speak, off-budget but ought to belong on the centre stage. For years, experts have argued the case for rethinking the Centre-state relationship regarding the police, divided between them by the Constitution. The time to debate how the police should be financed and regulated is running out.

Also read: Some hits and misses for India’s agricultural sector in Budget 2023

Devil in the details

Even though Budget 2023 has only a small expansion of funding for the police — with Rs 1,29,627.52 crore committed, over the revised estimate of Rs 1,20,026.19 for FY 2021-2022 — there is some welcome evidence that the Narendra Modi government has its priorities right. Forensic science and criminology facilities—correctly identified by Union Home Minister Amit Shah as the key to credible investigations—have received capital allocations of Rs 28.25 crore, almost thrice as much as last year. The states will get another Rs 700 crore, sharply up from Rs 250 crore.

The cash-strapped Intelligence Bureau, which received just Rs 62.69 crore for capital expenditure in FY 2021-2022 and Rs 65.71 crore in last year’s revised estimates, will have Rs 255.06 crore to spend this fiscal year. The National Intelligence Grid, the master database structure that links state and central databases, will also get a sharp increase in funding.

Like so much else to do with internal security, though, the devil is in the details.

From the most recent data available—published last year by the Bureau of Police Research and Development (BPRD)—it is clear,f cash-strapped state governments just aren’t able to commit cash for the police. In the year of the lethal 26/11 Mumbai attack, which claimed to have transformed government attitudes toward internal security, the states and Union territories spent Rs 26,269.09 crore on their police forces or 3.88 per cent of their budgets. Last year, the ratio was up just marginally to 4.13 per cent—and the numbers are even more depressing on close examination.

The Lashkar-e-Taiba death squad that attacked Mumbai, scholar Paul Staniland has recorded, encountered police that were “understaffed, undertrained, and technologically backward”. That year, the states and Union territories spent Rs 413.36 crore on training police personnel, which is nearly 1.5 per cent of the Rs 26,269.09 crore of the police budget—and authorities vowed reforms.

In 2022, the money spent by states and Union territories on training police was Rs 1,652.88 crore—two-thirds of the Rs 2,480.02 crore budgeted for the purpose and less than one per cent of the expenditure on the armed forces.

Expenditure on police training in the states and Union territories has actually diminished. There has also been a recurrent pattern of state governments and Union territories failing to spend funds budgeted for police. The states and Union territories spent only Rs 1,53,766.19 crore of the Rs 1,78,338.47 crore they were allotted in FY 2020-2021, and Rs 1,67,489.15 crore of Rs 1,94,116.34 crore in FY 2021-2022.

The malaise is endemic. The Jammu and Kashmir police, operating in India’s most dangerous environment, spent just Rs 82 crore of the Rs 102.4 crore it was allotted for training last year. The Union territory performed even worse on modernisation, spending just Rs 16.57 crore out of the Rs 150 crore budgeted.

Even in well-off Maharashtra, economists Renuka Sane and Neha Sinha have recorded, budgets “barely allocate funds for operational expenses of running police stations or maintenance costs for computer systems, arms, and ammunition”. Elsewhere in India, low budgets have compelled police to cut back on essentials like fuel and ammunition. The lack of police welfare infrastructure has incentivised corruption.

Also read: Budget 2023: An election-year bonus for the super-rich. No, Modi govt hasn’t lost it

Flailing Leviathans

The rationale for spending decisions isn’t always evident in the numbers. The Delhi Police has been allocated Rs 1,019.92 crore for capital expenditure, almost twice as much as the Border Security Force, which is set to receive Rs 555.77 crore, and is well over five times more than the critical Indo-Tibetan Border Police, which has been allocated Rs 174.61 crore. The Special Protection Group, assigned to protect the Prime Minister, has got Rs 77 crore for capital expenditure.

The core malaise in the states—spending too much on salaries and not enough on capacity-building—also afflicts the central forces. The Central Reserve Police Force, the core national police service, will spend Rs 31,154.09 crore on salaries this coming fiscal year. The force will have only Rs 618.14 crore, however, for capital expenditure.

Facing cross-border insurgencies and violence that threatened to overwhelm state police, the central government has relied on central forces since the early years after Independence. The numbers of central police organisations have steadily increased, BPRD data shows. From Chhattisgarh to Kashmir, though, central police forces have struggled — local forces have far superior local knowledge and social legitimacy.

For internal security planners, cutting central police numbers is not an option, since state police forces are already well below strength. The BPRD recorded that the state governments and Union territories have budgeted to provide 192 police officers for every 1,00,000 of India’s 1.2 billion population. Financial constraints, though, mean there are 150.8 police officers per 1,00,000 people, well below the United Nations norm of 250.

Then Home Minister P. Chidambaram raised alarm at the numbers in 2010, which, at about 160 per 1,00,000, were much the same as today. Telangana, where Maoist insurgencies have repeatedly erupted, should have 218 police per 1,00,000 residents. The state, the BPRD says, just has 131. Uttar Pradesh should have 185 but pays for 127. Bihar has just 73 per 1,00,000.

The lack of effective police forces has had real consequences for India. Local political actors—from caste élites to outright criminals—wield effective power. That has undermined the formation of a policy based on the rule of law. Anaemic police forces have often depended on brutality to assert state authority.

For decades, New Delhi has relied on the central police forces—and the military—to extinguish the many crises that confronted the country. The existing model has served to ensure order but not law.

Praveen Swami is ThePrint’s National Security Editor. Views are personal.