Despite there being no contemporaneous evidence, it has often been argued that the 1947 Radcliffe Award, which defined the boundary between India and Pakistan in Punjab, was ‘altered’ to give India three tehsils of Gurdaspur District—Gurdaspur, Batala, and Pathankot. This, ostensibly, was to enable India to get a road link with Kashmir.

However, historical records suggest that in order to gain more territory and encircle Amritsar, it was Pakistan that argued against the notional partition plan, which would have given it Gurdaspur. Further, it was forewarned about the possibility of the entire district being given to India even before the award was pronounced.

Pakistan contests notional plan—and getting entire Gurdaspur district

After the partition of India became imminent in June 1947, Mountbatten prepared a notional plan dividing the provinces into Indian and Pakistani zones, district by district, on a map based on the 1941 census. This was only a temporary working arrangement devised to help divide assets, services, and staff, and to set up administrative arrangements pending the final outcome of the Boundary Commissions of Punjab and Bengal.

In this notional plan, Gurdaspur district had been shown as part of Pakistan. However, the Punjab Boundary Commission ended up awarding three of its tehsils (Gurdaspur, Batala, and Pathankot) to India, and one (Shakargarh), to Pakistan.

Such deviation between the notional partition plan and the final award of the Boundary Commissions was nothing unusual. It also happened in the case of Bengal’s Khulna, a Hindu-majority district which ended up with East Pakistan, and Murshidabad, a Muslim-majority district which ended up with India.

Contrary to popular perception, no ‘notional award’ was ever passed by Radcliffe which gave the entire Gurdaspur district to Pakistan.

While attributing motives to Mountbatten on the Gurdaspur Award, many have overlooked that it was Pakistan itself which argued before the Boundary Commission to reject the idea of the entire Gurdaspur district coming to it. It apparently feared that by accepting the notional district-wise partition plan in this region, it would lose out on several other territories which it could have otherwise gained. Thus, instead of district-wise division, it argued for sub-district or tehsil-wise division in the hope of maximising its gains and also encircling Amritsar.

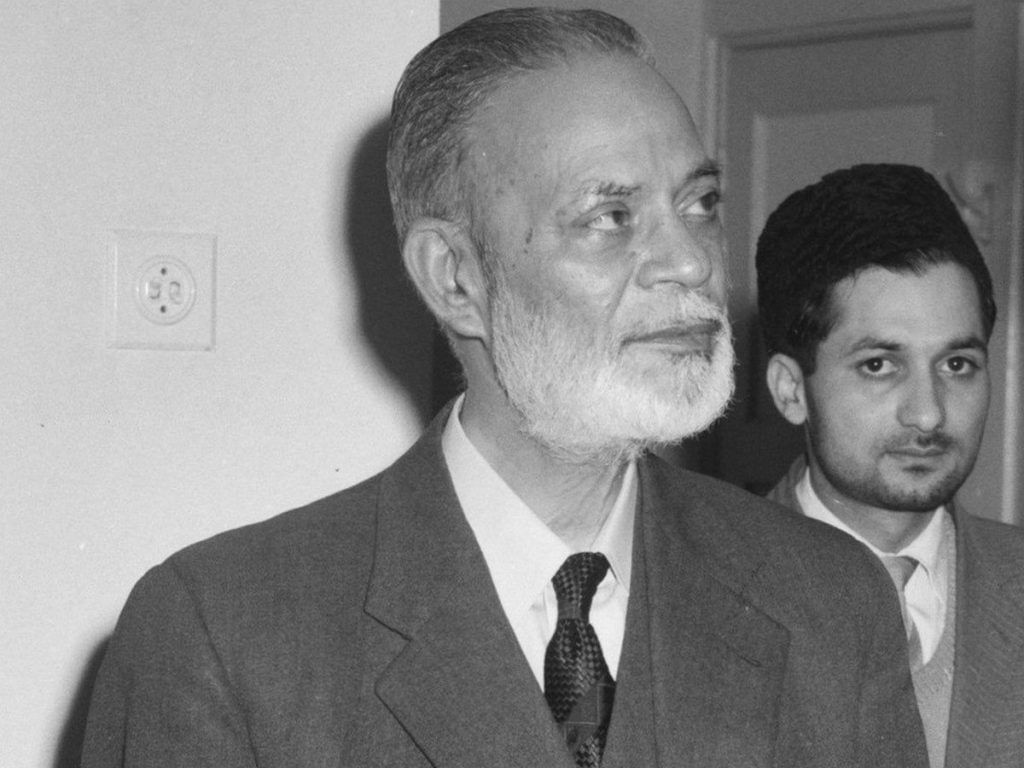

Zafrullah Khan admits Pakistan overplayed its hand

The Muslim League’s case before the Punjab Boundary Commission was argued by Zafrullah Khan. In his memoir The Forgotten Years, he gives an account of how Pakistan presented its case and, in the process, admits to the reasoning that cost it most of Gurdaspur.

Khan writes, “the main contest centered around Gurdaspur District, Ferozepur District and parts of Jullundur District with the crux of the matter being how to interpret and apply the expression ‘contiguous Muslim majority areas’.”

He went on to explain why Pakistan’s case was built on using the tehsil or sub-district as the unit for determining majority areas rather than villages or police stations, which he wrote would have made the boundary line “completely crazy” and unworkable.

He, thus, added: “So one could take a Sub-District, as we did or one could take a District as a unit. The choice was a difficult one.

If a District were taken as a unit then the notional partition which had already been put into effect for the purpose of administration ad interim, would have to be confirmed and that would give the whole of the Gurdaspur District to Pakistan. But the risk was that if we confined our case to Districts, it might be argued that we were happy with the notional partition and our claim might be whittled down further to our serious prejudice.

Adopting the tehsil as a unit would give us the Firozpur and the Zira tehsils of Ferozepur District, the Jullundur and Nakodar tehsils of Hoshiarpur District. The line so drawn would also give us the state of Kapurthala (which had a Muslim majority) and would enclose within Pakistan the whole of Amritsar district, of which only one tehsil, Ajnala had a Muslim majority. It would also give us Shakargarh, Batala and Gurdaspur tehsils of Gurdaspur District. One could also take as units what, in the Punjab are known as doabs, that is to say, the area between two rivers. If the boundary had gone by doabs, we could have got not only the sixteen districts which under the notional partition, were later, given to us but also Gurdaspur District and Kangra District in the mountains. Had any of these units been adopted, the boundary line would have been more favorable than what it is now.”

Khan’s own words about enclosing Amritsar make it clear that in chasing a larger territorial sweep, Pakistan undermined its claim to Gurdaspur itself. Khan then describes how Sir Cyril Radcliffe, Chairman of the Radcliffe Committee, proceeded to make his final decision:

“Everybody knew it already that there was going to be no unanimous or majority report. The non- Muslim Commissioners took one view while the Muslim commissioners had just the opposite view. Consequently the umpire had to give his award. After studying the record he held discussions with the Members of the Commission at Simla. We were told by the Muslim Commissioners that while Sir Cyril was not quite definite about Gurdaspur District, he was quite clear that the two sub districts of Ferozepur District- the sub district of Firozepur itself and the sub district of Zira being Muslim majority areas and contiguous to the rest of the Muslim block from part of Pakistan….”

It is evident that since the Hindu-majority tehsil of Pathankot gave India a land route to Kashmir and would have come to India as per Pakistan’s own contentions, even if the other two tehsils had been awarded to Pakistan, India could still have secured a land route to Kashmir by connecting Pathankot with Hoshiarpur District. As historian Shereen Ilahi noted in a 2003 paper: “It would have been arguable if there was a controversy regarding the other two Muslim majority tehsils being awarded to India but there can hardly be any regarding Pathankot.”

However, since the other two tehsils did not have any connection with Kashmir, it was later argued that Gurdaspur had been given to India with some malafide intent on Kashmir.

The Wavell Plan and Gurdaspur

While Radcliffe was not obliged to follow any previously made plan on the subject, it cannot be ruled out that, apart from the reports and submissions made before the Commission, he may also have taken earlier proposals into consideration while exercising his discretion.

One such plan was Lord Wavell’s Boundary Demarcation Plan of 7 February 1946, which allocated to West Pakistan the territories of Sindh, North-West Frontier Province, British Baluchistan, and the Rawalpindi, Multan, and Lahore divisions of Punjab, excluding Amritsar and Gurdaspur districts, as laid out in Volume VI of Transfer of Power.

Wavell, who was viceroy of India until 21 February 1947, had called for Amritsar going to India as it was the holiest city of the Sikhs. For Gurdaspur, his reasoning, as academic Ishtiaq Ahmed put it, was that it “must be awarded to India otherwise Amritsar would be surrounded by Pakistan in the north and the west which could jeopardize its security.”

Ahmed further wrote: “The Ferozepur District in the South had a non-Muslim majority even though its Zira and Ferozepur tehsils had a Muslim majority. Amongst other considerations, Wavell at that time was thinking it terms of contiguous districts and not tehsils as the unit of demarcation of the boundary.”

In his 7 February 1946 letter to Secretary of State for India Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Wavell explicitly stated:

“In the Punjab the only Moslem majority district that would not go into Pakistan under this demarcation is Gurdaspur (51 per cent Moslem). Gurdaspur must go to Amritsar for geographical reasons and Amritsar being a sacred city of Sikhs must stay out of Pakistan. But for this case for importance of Amritsar, demarcation in Punjab could have been on divisional boundaries. Fact that much of Lahore District is irrigated from upper Bari Doab canal with head works in Gurdaspur district is awkward but there is no solution that avoids all such difficulties.”

Apart from the fact that the headwaters of all the canals which irrigated Amritsar lay in Gurdaspur, and it was important to keep them under one administration, Sikh religious concerns that weighed before Wavell in 1946 were also kept in mind by Radcliffe in 1947.

“Even according to Pakistan’s representative on the Commission, Justice Din Mohammed, Radcliffe’s main reason for awarding Batala and Gurdaspur tehsils of Gurdaspur District to India was that their award to Pakistan would have isolated the important Amritsar District from surrounding Indian soil,” wrote Lord Birdwood in Two Nations and Kashmir.

In Punjab, the Radcliffe Award more or less upheld the Pakistani contention that the province should be divided on the basis of religious contiguity. Clearly, the Muslim League was the ‘winner’, with only three Sikh-majority villages on the eastern bank of the Sutlej being taken from the Kasur tehsil of Lahore District and given to India to make the border equidistant from Lahore and Amritsar. The Radcliffe Award, as pointed out by Ishtiaq Ahmed in his book Jinnah, was 99.9 per cent identical to the Wavell Demarcation Plan of 7 February 1946, which had given Ferozepur and Gurdaspur districts to India.

Also Read: How Maharaja Hari Singh’s indecision led to Pakistan’s economic blockade of Kashmir

Jinnah & Muslim League were forewarned Gurdaspur would go to India

It is not that Jinnah or the Muslim League’s representatives on the Commission were unaware of the Wavell Plan of 1946 or the likelihood of the entire Gurdaspur district being given to India by Radcliffe in 1947.

The last meeting of the Commission was held at the United Services Club in Simla. Justice Muhammad Munir confirms in his memoirs that he and Justice Din Muhammad even briefly contemplated resigning when after an interview with Sir Cyril at Simla, the latter “came out with the impression that practically the whole of Gurdaspur, with a link to Kashmir, was going to India”.

Even when writing about the award later, while alleging alteration in respect of Ferozepur, Munir made no such claim regarding Gurdaspur because, like Justice Din Muhammad, he knew that the entire district would in all likelihood go to India. On Gurdaspur, he wrote that none of their contentions had been accepted by Radcliffe, thereby confirming that the Boundary Commission’s chairman’s mind had already been made up.

As Ishtiaq Ahmed noted in an article, Kirpal Singh quoted Justice Muhammad Munir in the Tribune on 26 April 1960, where the latter confirmed knowing from the outset that Gurdaspur would go to India:

“Today, I have no hesitation in disclosing… It was clear to both Mr. Din Mohammad and myself from the very beginning of the discussions with Radcliffe that Gurdaspur was going to go to India, and our apprehensions were communicated at a very early stage to those who had been deputed by the Muslim League to help us.”

It is therefore evident that after Simla, everyone in the League was aware of Radcliffe’s intention to give the entire Gurdaspur district to India, since their own representatives had threatened to resign on that count.

If Radcliffe’s mind was already made up and he was inclined to give Gurdaspur to India,why would he require someone to influence him subsequently to do what he had already contemplated doing on his own earlier? Clearly, the question of anyone persuading him to move Gurdaspur from Pakistan to India subsequently does not arise. Hence, all arguments to the effect that there was some change in the Gurdaspur Award after Simla, which was prejudicial to Pakistan, are ill-founded. The only change that occurred thereafter benefited Pakistan, as it ended up getting Shakargarh instead of the entire district being given to India as per the Wavell Plan.

The Radcliffe Award was passed on 17 August 1947 and was criticised in the Pakistani media on account of what was perceived as the unjust mutilation of Punjab, and not because it provided India a road link with Kashmir. Immediately thereafter, there is a voluminous record of meetings and correspondence between Jinnah, Liaquat Ali Khan, Mountbatten, and General Ismay on a host of subjects, but none in which Pakistan accuses Mountbatten of influencing the award with any ulterior intent regarding Kashmir.

At this time, Pakistan was confident of securing Kashmir’s accession and did not want to antagonise the Maharaja or cast aspersions on his intent. Therefore, there was no allegation linking the Gurdaspur Award with Kashmir in any of its communications with the princely state. It was only after Kashmir’s accession to India that, in a message from the Pakistan Broadcasting Service, Lahore, on 30 October 1947, Jinnah described the Boundary Commission Award as an “unjust, incomprehensible and even perverse award… but we have agreed to abide by it and it is binding upon us.”

The importance of Gurdaspur—and the realisation that the Award was a setback for Pakistan—dawned upon it only after the Indian forces entered Kashmir.

As Zafrullah Khan later admitted, “the inclusion of Gurdaspur District in East Punjab was a great blow to us because it facilitated the Indian intervention in Kashmir, as from the plains only Gurdaspur District could give the Indians an access to Kashmir.”

Whatever the controversy over the inferences, deductions, or hypotheses propounded by forensically analysing the conduct of Mountbatten or Radcliffe on the Gurdaspur Award, it is evident that nothing so far suggests that the Punjab Boundary Commission passed its award on Gurdaspur with an eye on Kashmir. Nor is there anything to indicate that it influenced the Maharaja to such an extent, or in such a manner, that he acceded to India.

The writer is an independent researcher and author of the book ‘Meghdoot: The Beginning of the Coldest War’. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)