New Delhi: The country’s apex food regulator has decided to adopt the standards of the Indian Council of Medical Research-National Institute of Nutrition (ICMR-NIN) for defining, for the first time, food that is high in fat, sugar or salt (HFSS), ThePrint has learnt.

Salt, sugar and fat are considered nutrients of concern and are harmful for health in excessive amounts.

The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) is set to include the definition of HFSS under its FSS (labelling and display) regulation, officials in the regulator said.

This regulation will then form the basis to mandate norms related to front-of-pack nutrition labelling (FOPNL) for all packaged food items, which the FSSAI is expected to release by mid-July on the directions of the Supreme Court.

The Dietary Guidelines for Indians, 2024, released by ICMR-NIN, state that HFSS foods are those foods that are prepared with excessive cooking oils or fats or high amounts of added sugar and salt.

They add that ultra-processed food (UPF) is often HFSS, and regular consumption of such food is known to increase the risk of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases, among others.

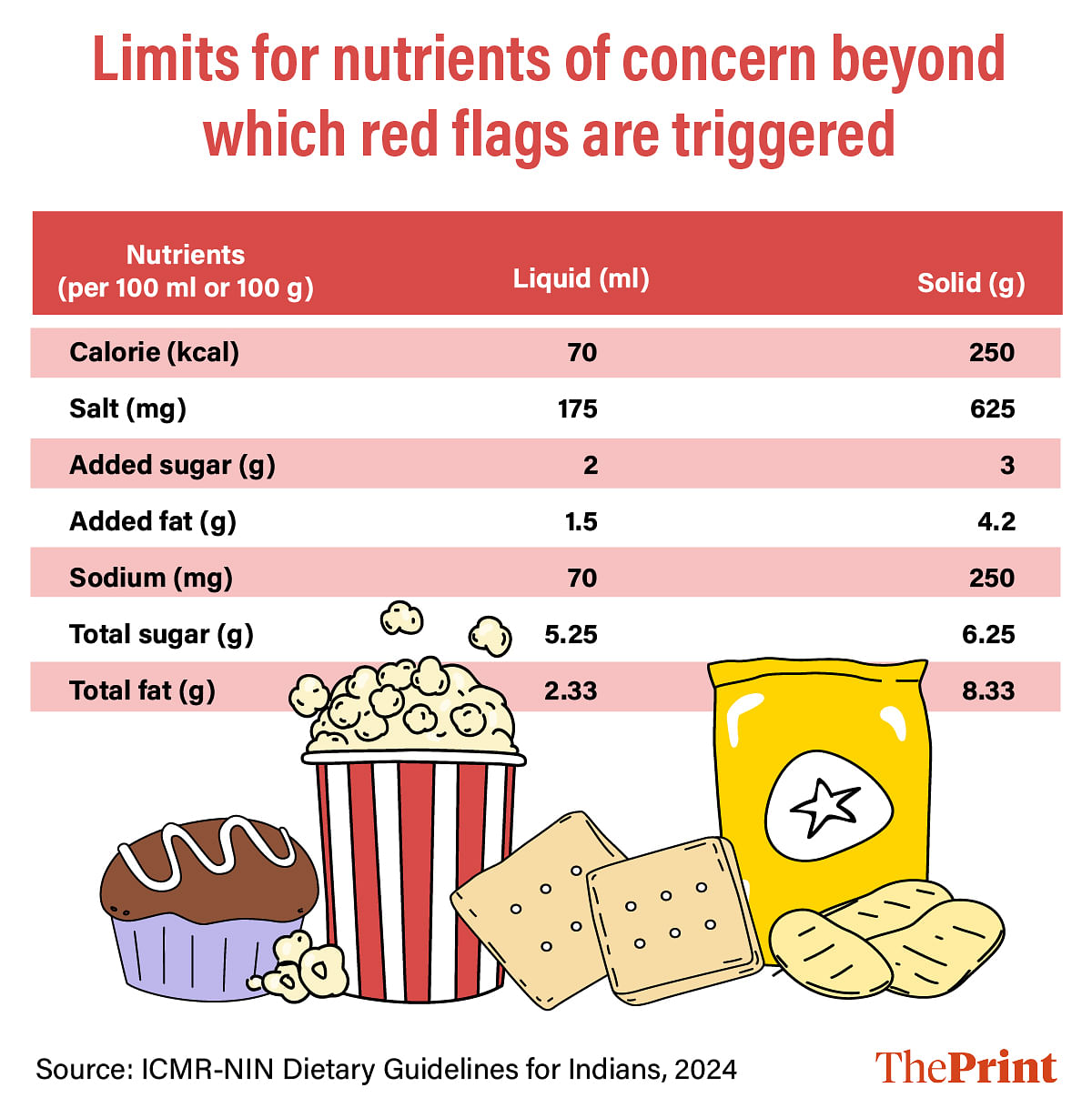

The guidelines, in a first, also lay down thresholds for various nutrients of concern and state when certain food items can be categorised as HFSS.

“A decision to adopt NIN guidelines was taken after a working group constituted for the purpose in April this year recommended so. It was also validated by a NITI Aayog panel that is working on nutrition policy,” a senior FSSAI official told ThePrint.

The official added that a scientific panel was now giving the final shape to the FOPNL policy.

ThePrint has reached out to FSSAI chief executive officer G. Kamala Vardhan Rao over email for his comment on adoption of the HFSS definition. This report will be updated if and when a reply is received.

Nutrition experts welcomed the decision, saying it may be a significant step towards improving public health and empower consumers to better understand the nutritional value of the product they are consuming and make healthier decisions.

“There has been no legal definition of what constitutes HFSS food and this made it hard for regulators to enforce guidelines or for consumers to identify unhealthy options,” public health nutrition specialist Dr Sujeet Ranjan told ThePrint.

Dr Arun Gupta, convener of nutrition think-tank Nutrition Advocacy in Public Interest, too said there was a need for convergence between national guidelines and regulation.

“In this context, I would be happy if the FSSAI bases its FOPNL policy on HFSS thresholds set by the ICMR-NIN,” he said.

Also Read: Colour coding or star rating—FSSAI food labelling plan can trigger a new nutrition war

Glare on nutrients of concerns

The dietary guidelines that came out last year state that high fat foods and high sugar foods are energy dense: high in calories but poor in vitamins, minerals and fibre.

Regular consumption of these foods not only causes obesity but also deprives one from taking healthy foods that provide essential macronutrients, fibre and micronutrients, such as vitamins, minerals, phytonutrients and bio-active substances.

Lack of essential amino acids, fatty acids and micronutrients in the diet can cause anaemia, affect cognition, learning ability, memory and increase the risk of non-communicable diseases, say the guidelines.

High fat or high sugar foods further cause inflammation and affect gut microbiota, which changes quickly with diet. Foods with high salt increase the risk of hypertension and tax the kidneys; hence, high salt intake is unhealthy, the guidelines stress.

“These guidelines are based on scientific evidence and are the result of deliberations with a large number of nutrition and health specialists that stretched on for years,” Dr Hemalatha R, former director of ICMR-NIN, and chairperson of the expert committee which had prepared the guidelines, told ThePrint.

In line with international norms

The World Health Organization (WHO) says total fat intake by a person should not exceed 30 percent of total energy and, taking into consideration inherent fats naturally present in foods which have several health benefits, an allowance of at least 15 percent energy should be given for inherent fats. The rest 15 percent of energy may come from visible fat or cooking oils or fats.

Hence, food that contains more than 15 percent of energy from any cooking vegetable oils or fat is defined as HFSS.

NIN identifies all deep-fried foods and foods prepared with high quantities of oil/fat such as French fries, samosa, kachori, puri, savouries, desserts, biscuits, cookies, cakes, parathas or even some curries as HFSS.

It says that apart from ghee or butter, which are saturated fats, coconut oil, palm oil and vanaspati also contain saturated fats, and hidden sources of saturated fat include red meat and high fat dairy products.

The guidelines state that the intake of salt above 5g per day or sodium 2g per day is beyond the healthy range.

They add that processed or pre-packaged foods like chips, sauces, biscuits, bakery products as well as home-prepared foods like savoury snacks, namkeen, papads and pickles as well as beverages where salt is added by the manufacturer or cook, are HFSS.

Consumption of sugar that contributes more than 5 percent of total daily energy intake—equivalent to over 25g per day based on a 2,000-calorie diet—is defined as “high sugar” intake.

The WHO is considering revising its recommendation and reducing calories from sugar to less than 5 percent of total energy intake per day.

“Limiting sugar to 25g per day is better for health. If possible, added sugar may be completely eliminated from one’s diet as it adds no nutritive value other than calories. Calories are healthy only when accompanied by vitamins, minerals and fibre,” the NIN guidelines note.

Added sugars refer to sugars and sugar syrups added to foods and drinks during processing and preparation and this includes sucrose, jaggery, honey, glucose, fructose and dextrose.

“Adding sugar over and above what is naturally/inherently present in foods increases the total calorie intake but adds no nutritive value,” the guidelines state.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)