Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://englishdev.theprint.in/subscribe/

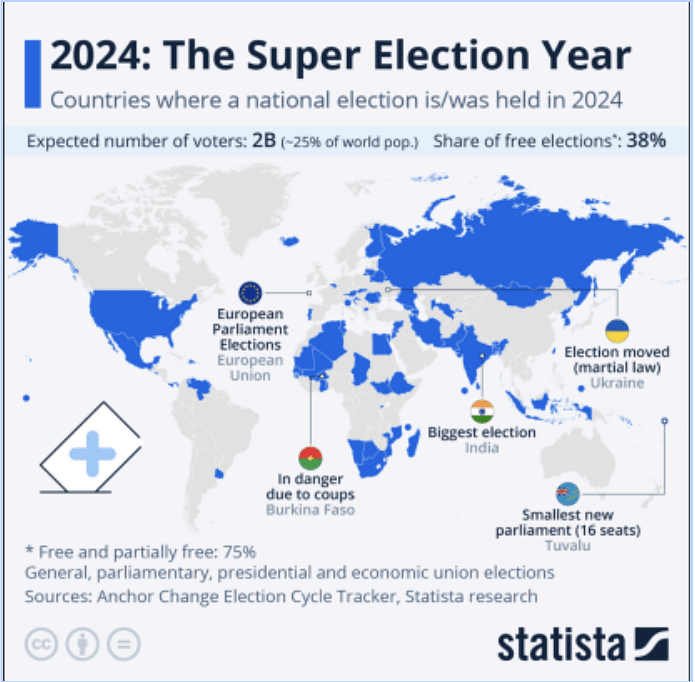

History was made. On June 2, Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo of the Morena Party became the first female president of Mexico, wiping out her main competitor, Xóchitl Gálvez. In 2024, more than 2 billion people are expected to vote, but the results of Mexico’s elections will go down as a milestone for women’s progression. As a 16-year-old student, passionately interested in global politics and gender, this was a welcome development in international geopolitics where elected women leaders are still a rarity. However, as I delved deeper into the news, I realised a grim truth endures- one that is as true in India as it is in Mexico, the United States, the UK and more countries than I can name. Despite a huge step forward in women’s empowerment with Sheinbaum’s election, women in Mexico are far from safe as femicides and gender-based violence are rampant. Now more than ever, as Mexico becomes the flag bearer of change, there is a unique opportunity to prioritise the issue of gender-based violence and enact meaningful change.

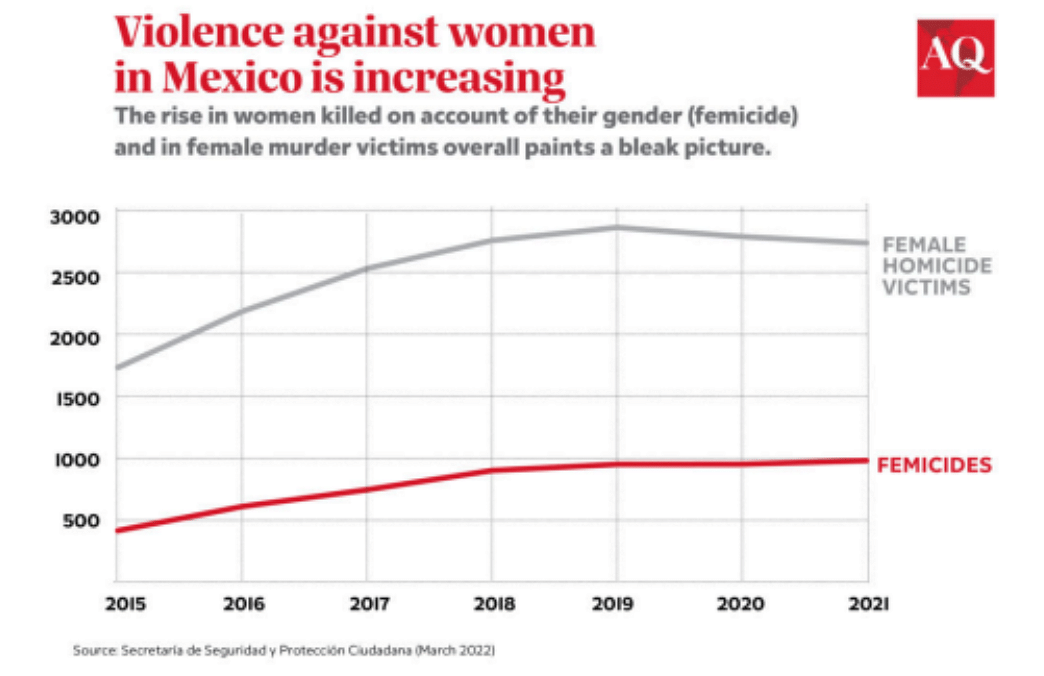

Through her election campaign, Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo has laid out her vision. From reducing the deficit in 2025 to a maximum of 3.5% of GDP to her focus area of moving away from reliance on traditional fossil fuels, it is clear that Sheinbaum has clear strategies on how to combat the complex issues that have been pervasive in Mexico. Hence, it is a great disappointment that the issue of femicides in the country has been addressed sparsely and imitatively. In a country where, according to the national survey data, 70.1 per cent of women have experienced some form of violence in their lifetime, not having a clear plan on this issue is not an option. In the latest Mexico Peace Index (MPI), it was found that while overall peacefulness in Mexico has improved in recent years, there is a significant rise in gender-based violence. The MPI’s violent crime indicator includes four components: robbery, assault, family violence, and sexual assault. Over the past eight years, robbery and assault rates have fluctuated within a normal range, staying within 35% of their 2015 levels. However, family violence and

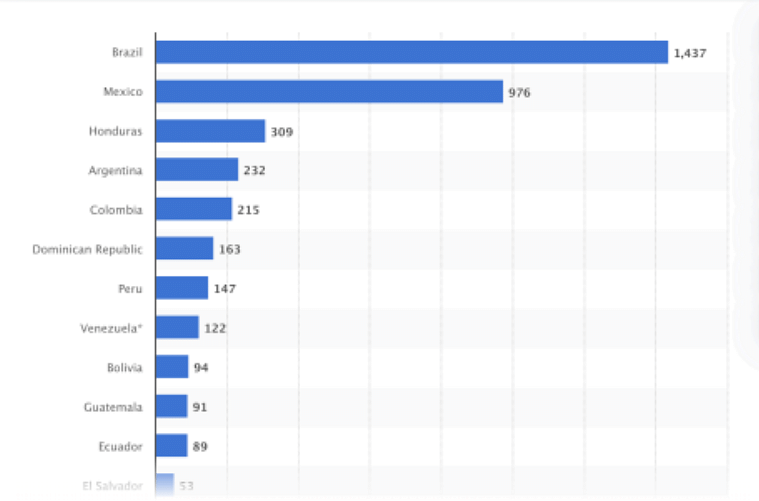

sexual assault rates, both associated with gender-based violence, have consistently increased each year, more than doubling since 2015. As a result, femicides are brought to the forefront. Femicide is defined as the criminal deprivation of the life of a female victim for reasons of gender. This has been a dominant issue in Mexico where the statistics on gender-based violence are disconcerting: around ten women are killed every day in the country with one in four female killings being classified as femicides. With the number of disappearances of women and girls tripling over the last three years and Mexico being the second country with the highest number of femicides in Latin America, the time for change is now.

Sheinbaum has pledged to continue with her mentor and predecessor’s policies on these issues, raising concerns as Andrés Manuel López Obrador was far from successful in resolving these issues. In 2018, López Obrador won the presidency with promises to demilitarize the fight against drug cartels, advocating for peace through “hugs, not bullets.”He aimed to tackle the root causes of crime with social welfare programs instead of violent confrontations. An example of this approach was the release of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s son in 2019 to prevent bloodshed. Despite his promises, López Obrador didn’t demilitarize public security. He merged law enforcement agencies into the National Guard, intended to be under civilian control, but then placed it under the Secretary of Defense. Critics argue that described as populist, was meant to create the impression of addressing crime while the National Guard expanded its role, even

managing infrastructure and airports, raising concerns about corruption. Meanwhile, criminal groups have grown stronger. A report by the Crisis Group noted that large military deployments in cartel-affected areas led to minimal crime-fighting. Instead, unwritten rules emerged, allowing criminal groups to reduce visible violence in exchange for authorities ignoring certain illegal activities.

This remains relevant to the issue of femicides and gender-based violence as there is a thorough line between militarization and gender-based violence in Mexico, say experts. This is further supported by the fact that Severe violence against women is most prevalent in remote Mexican states like Oaxaca, Veracruz, and Chiapas, where criminal organizations are widespread. Despite not always reporting the highest numbers of femicides or gender-based violence due to victims’ fear and limited law enforcement, these areas remain particularly dangerous for women. A 2021 UN Development Programme study highlights that in regions controlled by cartels, violence against women escalates, with families often too afraid to report incidents. This violence is used by criminal groups as a means of intimidation and dominance, perpetuating a cycle of abuse. Therefore, even though Sheinbaum has recognized femicides and gender-based violence as a key component of Mexico’s context of insecurity, she still fails to incorporate a human rights lens

that hat can move the country away from the militarized and punitive approaches that have led to the current crisis. She has advocated for all homicides of women to be treated as femicides and suggested that each Mexican state establish a specialized prosecutor’s office for femicide cases. While these initiatives are positive, the continued militarization of the country, along with associated lethality, impunity, and human rights violations by the military, could negate any progress.

Instead of following in the footsteps of López Obrador, Sheinbaum should come up with structured steps to combat the issue. First, to improve gender-based violence (GBV) data in Mexico, in Mexico, it’s crucial to enhance data quality through collaboration between the state and civil society, adopting a feminist approach to data science. Understanding the links between femicides, disappearances, and other GBV forms like sexual exploitation requires coordinated efforts among government, activists, and organizations, despite the risks involved. Prevention of structural gendered violence should be prioritized by reassessing security strategies with a feminist perspective, moving away from militarized responses. Additionally, protective measures must be redesigned for women searching for the disappeared, recognizing them as human rights defenders and offering appropriate protection mechanisms tailored to their needs.

While the choice of a female head of state is a unique opportunity to spotlight crimes against women in Mexico, the fact remains political leaders regardless of gender must urgently recognize this issue and commit to implementing impactful policies and programs that prioritize the safety and empowerment of women in their countries.

In conclusion, it is a crucial moment to prioritize gender-based violence and drive significant change. In 2024 as large parts of the world vote or will be voting, it is a crucial moment to prioritize gender-based violence and drive significant change. Political leaders must urgently recognize this issue and commit to implementing impactful policies and programs that prioritize the safety and empowerment of women in a place where this has been lacking for years.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.

Very good piece